Document 11096569

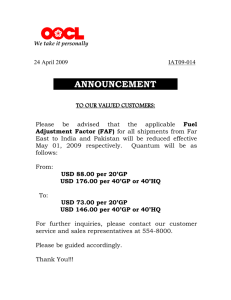

advertisement