Document 11096449

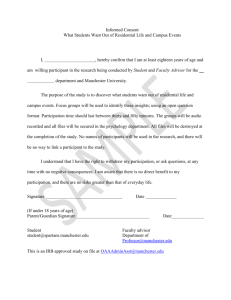

advertisement

Manchester On Foot A stroll through history Downtown Manchester A self-guided walking tour of downtown Manchester and the Amoskeag Millyard Walking Tour #2 - Downtown Manchester - 1.32 miles - total time without stops 50 minutes - total time with stops 2.25 hours 1. Manchester City Hall The Tour begins at the Manchester Information Center located on the corner of Elm Street and Merrimack Street. Leaving the Manchester Information Center, turn right and head north on Elm Street to City Hall, located at One City Hall Plaza across from Hanover Street. (.15 miles) Key stops may include: 1. City Hall – 20 minutes 2. NH Institute of Art – 20 minutes 3. Manchester Library – 10 minutes 4. Manchester Historic Assoc. – 15 minutes 5. Franco-American Museum – 15 minutes Wear comfortable shoes, and always cross at crosswalks. Use the pedestrian crossing lights whenever possible. Many of the buildings on this walk are public buildings or are otherwise open to the public. Take advantage of this whenever you can. View the interior architecture, learn more about the history of the building and see how it is being used today. Along the tour, you will see signs for the New Hampshire Heritage Trail. When completed, this will be a 230-mile walking path from Massachusetts to the Canadian border. The program is administered by the New Hampshire Division of Parks and Recreation, Bureau of Trails. More information is available at www. nhtrails.org. The First People to live in the area that is now Manchester were members of the Abenaki tribe, who fished at the falls on the Merrimack River 11,000 years ago. The first European settlers to the area came from Scotland and Ireland in the 1720s and in 1751 settled and incorporated the village of Derryfield, a modest community on the edge of the frontier. In 1810, its citizens changed the town’s name to Manchester, in honor of England’s great industrial city. They were looking toward a future they could barely imagine, as the only industry here at that time were the traditional small saw and gristmills. The Manchester we know today is a product of the Industrial Revolution. The city’s creation and growth are largely the legacy of one entity: the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company (The Amoskeag). The Amoskeag was incorporated in 1831, and operated for more than a century before closing its doors in 1935. In the early 20th century, the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company was the largest producer of cotton textiles in the world. The company’s owners also bought the waterpower rights to the swift-flowing Amoskeag Falls and purchased 15,000 acres of land from farmers on the east side of the river. This enabled the company to control the future shape of its millyard, and also to shape the growth of the city that would support its industrial operations. The Amoskeag laid out the city’s streets and built mills, canals and housing for workers. It then sold over 14,000 surplus acres of land for business blocks and residential neighborhoods. The company gave parkland to the city and sold lots at low cost for municipal buildings, schools and churches. The result is Manchester – the largest planned city in New England, and a true success story of early urban planning in America. The red-brick “mile of mills” that stretches along the east side of the Merrimack River still anchors the city firmly to its industrial past. But there is much more to Manchester’s history than the story of one company. The thriving city has always been a magnet for ambitious entrepreneurs, hopeful immigrants, and a long line of imaginative dreamers, planners, and doers. The evidence of Manchester’s rich past is everywhere around us, most notably in the buildings, monuments and other sites you will see today. Greater Manchester Chamber of Commerce 54 Hanover Street, Manchester, NH 03101 www.manchester-chamber.org Start in the courtyard just south of Manchester City Hall. Notice Manchester’s city seal set into the brick in the center of the courtyard. Manchester’s first town hall was built on this spot in 1841. It was a simple wooden building with a cupola. The top floor contained an armory for the local militia. Unfortunately, a wayward spark ignited the gunpowder, causing the building to burn to the ground in 1844. Not surprisingly, soon after this Manchester purchased its first two fire engines. The town also hired Edward Shaw, a Boston architect, to design a bigger and better town hall. This building was completed in 1845, just in time for Manchester’s incorporation as a city in 1846. The once small village had grown into a bustling city of over 10,000 people. The Mirror Block (Daily Mirror Office Building) or Old Post Office building was constructed in 1876 in the Italianate style. It housed the post office and the offices and pressrooms of the John B. Clark Publishing Company, which published the Manchester Mirror and other newspapers. The Athens Building which houses the Palace Theatre (80 Hanover Street) (.26 miles) was built in 1914. The exterior of the Athens Building, which extends to the corner of Chestnut Street, is much simpler and more modern than the 19th century buildings near it. The Palace is one of 450 “Palaces” of the same design in the United States, including one on Broadway in New York City. The stages and backstage areas in these theaters were all similar in design and size, making it easier for traveling performers to set up and perform. The Palace was one of the first buildings in the country to have an air conditioning system that involved a clever use of electric fans and blocks of ice. Be sure to poke your head in and view the inside of the theatre if it is not in use. Continue east on Hanover Street, crossing Chestnut Street. Notice the Post Office Building on the left, which will be mentioned later on this tour. Walk to the corner of Hanover and Pine Streets. Manchester City Hall was designed in the Gothic Revival style, complete with buttresses and arched windows. This style was often used for churches and academic buildings, but has seldom been seen in government buildings. If you enter City Hall and climb the staircase, you View of the east side of Elm Street, showing the will see “Art on the Wall”, a venue that allows Amoskeag Bank; Bartons; and the Merchants Bank. To the right is Manchester Street. local artists to display their work. City Hall is open Monday through Friday, from 8:00am to 5:00pm. Art work is always for sale, and the artists change every two or three months. The New Hampshire Institute of Art’s Fuller Hall (.36 miles) was constructed in 1915 as the headquarters for the New Hampshire Fire Insurance Company. The architect, Edward L. Tilton, chose the classical-revival style, complete with massive columns, to convey the company’s status as a thriving and important institution. After the company moved to new quarters in 1951, the building was used as a bank. The building was acquired by the New Hampshire Institute of Art in 2000. The abstract sculpture in front of the building is by Antoinette Shultze, the artist who designed the Mill Girl stature in the millyard. Inside Fuller Hall is a community gallery that is open to the public Monday-Friday from 9am-7pm, Saturday from 9-5pm, and Sunday from 1-5pm. In front of the Annex (the former Hillsborough County Court House) is a sculpture of Manchester resident and Revolutionary War hero Brigadier General John Stark, John Stark penned the phrase “Live Free or Die – Death is not the worst of evils,” which was adopted as New Hampshire’s state motto in 1945. Take a left on Pine Street. Walk one block and stop at the corner of Victory Park (corner of Pine Street and Amherst). 3. Victory Park Historic District Cross to the corner of Elm Street and Hanover Street. The Victory Park Historic District comprises 55 acres. The district was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1996 due to the significance of the social and architectural history of the park and the buildings in its vicinity. 2. Hanover Street On the south corner of Hanover and Elm Streets is the Amoskeag Bank Building (now Citizens Bank). This is Manchester’s first steel-framed “sky scraper,” built in 1914. of The Amoskeag Manufacturing Company laid out the streets in this part of the city in 1838. This park, originally called Concord Common, was the first of six parks deeded to the city by the Amoskeag for the benefit of its citizens. The park was originally twice this size, extending one more block to the west. At different times the park was used as a playground for children, as the site of an early farmer’s market, and at one time it was divided up into garden plots for the neighbors to use. The park was renamed Victory Park in 1929 as a memorial to the allied victory in World War I. in Take the diagonal pathway to the center of Victory Park. (.48 miles) Begin walking up Hanover Street to Chestnut Street. Hanover Street has always been a center of culture and commerce for the city. Much the block was destroyed in a devastating fire 1870, providing an opportunity for entrepreneurs to build some fine Victorian-era and early 20th century commercial buildings. The Harrington-Smith Block on your left was built in 1881 and is an Looking north east from Elm Street at the Opera House outstanding example of the Queen Block, also known as Harrington Block on Hanover Street. Anne Style. This building includes picturesque elements such as an interesting roofline, and a variety of building materials that create pattern and texture, including red pressed brick, limestone, granite, and terracotta. At one time the building housed the Manchester Opera House which eventually became the Strand movie theater. The building suffered a major fire in 1985 and the theater could not be saved, but this building and most of the structures on the north side of the street were renovated. The look of the original 19th century storefronts was reestablished, and the interiors of the buildings were remodeled while preserving as much of the original features as possible. The centerpiece of Victory Park is the Victory Monument, created by artist Lucien-Hippolyte Gosselin. Gosselin was educated in Paris and from 1920 until his death in 1940 he was a teacher at the Manchester Institute of Arts and Sciences. Near this monument is the René Gagnon Memorial, dedicated in 1995. Gagnon was a young worker at the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company before enlisting in the Marines in World War II. On February 23, 1945, he was called upon to carry a flag up Mount Suribachi on the Pacific island of Iwo Jima. Rene then helped to raise this flag on top of the mountain, an event that was memorialized in the famous photograph taken by Joe Rosenthal. Continue on the diagonal pathway northwest to the corner of Concord Street and Chestnut Street. Take a right and head north on Chestnut Street to the corner of Lowell Street. The brick building on the northeast corner of Lowell and Chestnut Street was Manchester’s First High School. (.58 miles) The city constructed the building in 1841 as a district school. It became the city’s first high school in 1848. In recent years the structure has suffered from a fire and other hardships and is awaiting rehabilitation. Turn right on Lowell and walk east to Pine Street. Grace Episcopal Church (106 Lowell Street at the corner of Pine Street) (.64 miles) was constructed in 1860, on the site of an earlier wooden structure. The influential English architect Richard Upjohn designed it. Upjohn built 150 churches in The U.S., the most famous being the Trinity Episcopal Church in New York City. British immigrants who worked in the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company gingham mills founded Grace Episcopal. This building is typical of the rustic English-Gothic style. St. Joseph’s Cathedral, almost directly across Pine Street, was built in 1869 to serve the predominantly Irish-Catholic parish of St. Joseph’s. The church was designed by Patrick C. Keeley, a gifted Irish-American architect who lived in Brooklyn, New York. The beautiful stained glass windows in the church were created in Innsbruck, Austria. Cross to the east side of Pine Street, turn right and head south on Pine Street to Concord Street. Edward L. Tilton has left the city with an enduring legacy of beautiful and useful buildings. This New York architect studied at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, and early in his career he and a partner designed the U.S. Immigration Station on Ellis Island. In addition to the four buildings seen on this tour, Tilton also designed the building for the Currier Museum of Art in Manchester which was completed in 1929. At Chestnut Street turn right and follow Chestnut north to Concord Street. Take a left and head west on Concord Street. On the right is the Franco-American Centre (.92 miles) building constructed in 1910 by the Jolliet Club, a social organization for people of French-Canadian heritage. In 1929 the ACA (originally Association Canado-Américaine, now ACA Assurance), bought the building and remodeled the exterior to include the monumental columns and massive wrought iron front door grate. In 1990 the Franco-American Centre, a newly formed cultural organization associated with ACA, bought the building. The Centre focuses its activities on promoting the history and culture of the French in North America. The Centre maintains an important research library and art collection. Continue west on Concord Street to Elm. Take a left on Elm Street and head south back to the Manchester Information Center. Total mileage for Tour 2 – 1.32 miles N The New Hampshire Institute of Art was founded in 1898 as the Manchester Institute of Arts and Science to promote education in the fine and domestic arts, and in the sciences. Its creation reflected the desire of Manchester citizens to pursue educational and creative opportunities in their spare time. The classical Institute building was designed by Edward Rantoul and completed in 1916. Eventually the Institute decided to focus solely on arts and crafts, training amateurs and professionals alike. In 1996 the Institute became a degree-granting institution and changed its name to the New Hampshire Institute of Art. This is the Institute’s main building and houses a gallery with the same hours as the Fuller Hall gallery. The Devine Millimet Building/U.S. Post Office building (.82 miles) was originally the United States Post Office and federal building, constructed in 1932. This building was one of the last buildings designed by Edward L. Tilton. A local financier named Frank Pierce Carpenter and his wife, Eleanor Blood Carpenter donated a new building for the city library. Carpenter hired architect Edward L. Tilton, and the Manchester City Library/Carpenter Memorial Building was completed in 1914. This building was particularly important to Carpenter as a gift to the city to promote education. He had not been able to afford to go to college, and his philanthropic gifts often reflected his desire that education be available to all. This classical building, reminiscent of Italian Renaissance palaces, is made of white Vermont marble on a base of gray New Hampshire granite. Over the front door you see a carving of an owl, which represents learning. It is holding the branches of native oak and pine trees. Walk inside to appreciate the center rotunda, wide marble staircase and second floor balcony that overlooks the center information desk. Cross Pine Street at the library crosswalk and walk south on Pine to Amherst Street. Turn right on Amherst. The Manchester Historic Association headquarters building on your left was built in 1931. This organization was founded in 1896, during the 50th anniversary of Manchester’s incorporation as a city. Like the library, this structure was the gift of Frank P. Carpenter, and was designed by his favorite architect, Edward L. Tilton. The building is an example of the classical BeauxArts style, though somewhat simplified and modernized due to its later era. The Historic Association is dedicated to preserving and sharing Manchester’s history and operates the Millyard Museum as well as this building, which houses the organization’s Research Center. The Research Center is open to the public Tuesday through Saturday from 10:00 am to 4:00 pm. Continue west on Amherst to Chestnut Street. S The public library system in Manchester started as the Manchester Athenaeum, a private circulating library organized in 1844. A free library was established in 1854 for all citizens to enjoy. By the early 20th century, the library had outgrown its home on Franklin Street. E W Continue south on Pine Street to the front of the library building. (.73 miles) View of 129 Amherst Street, home of the current Manchester Historic Association, looking south west at the corner of Pine and Amherst Streets.