Environmental Report The University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences

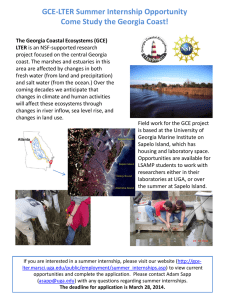

advertisement