A S U R V E Y ... C O M M U N I T I E... P R O V I D E R S : ...

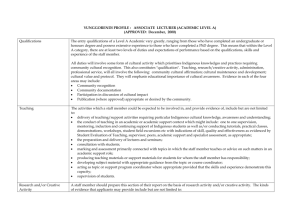

advertisement