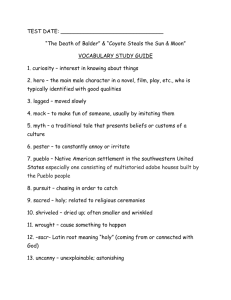

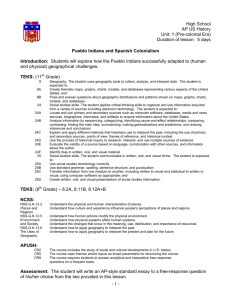

“Cultural Preservation and Societal Migration Among the 17th

advertisement