'Third' Italy by Universita'

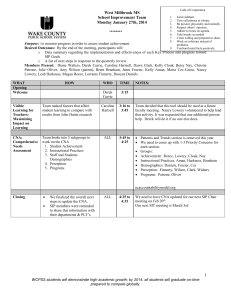

advertisement