in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the submitted to degree of

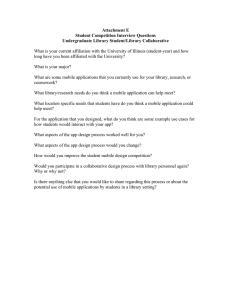

advertisement