ENGLISH LEARNER TOOL KIT

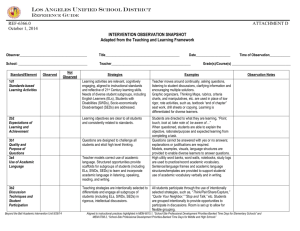

advertisement