DNASNOTE 3120 01 May 14 NAVAL ACADEMY SAILING

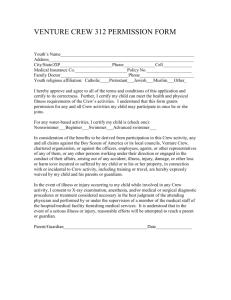

advertisement