Document 11070385

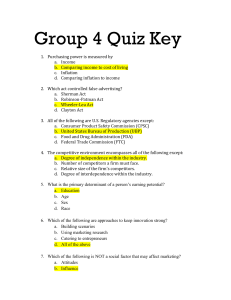

advertisement