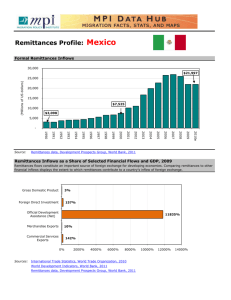

Close to Home The Development Impact of Remittances in Latin America

advertisement