THE ROSEMARIE ROGERS WORKING PAPER SERIES

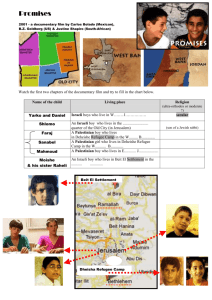

advertisement