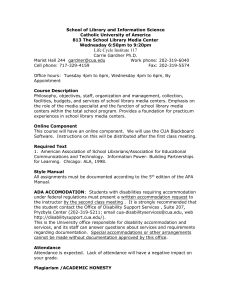

The Impact of New York’s School Libraries Phase II—In-Depth Study

advertisement