The Impact of New York’s School Libraries Phase I

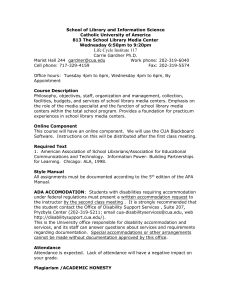

advertisement