Document 11057637

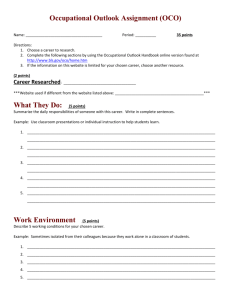

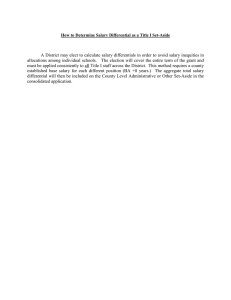

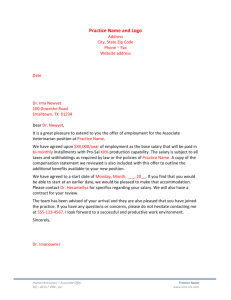

advertisement