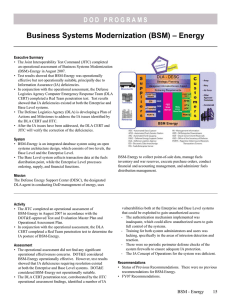

DEFENSE INVENTORY DOD Needs Additional Information

advertisement