GAO MILITARY TRANSFORMATION Actions Needed by

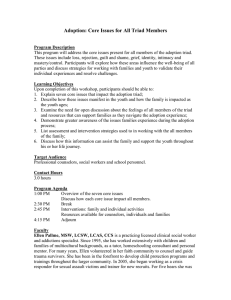

advertisement