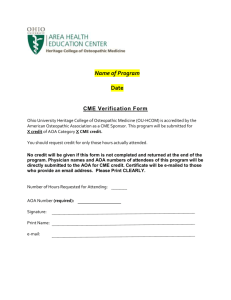

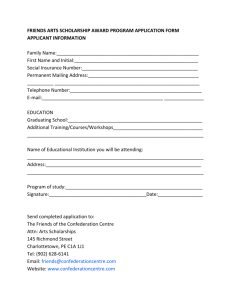

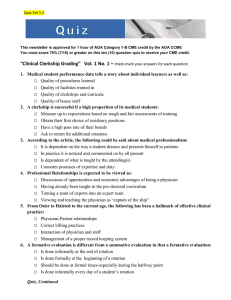

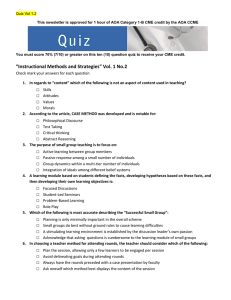

GAO

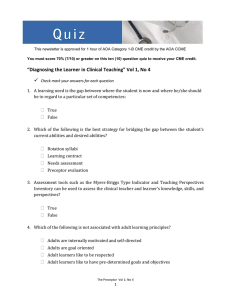

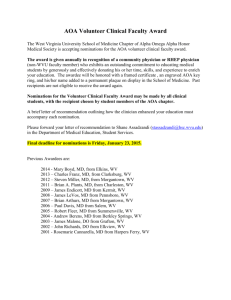

advertisement