GAO MILITARY DISABILITY SYSTEM Improved Oversight

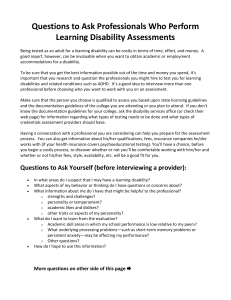

advertisement