GAO EXPLOSIVE ORDNANCE DISPOSAL

advertisement

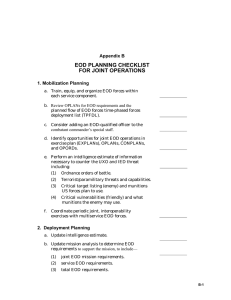

GAO April 2013 United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Committees EXPLOSIVE ORDNANCE DISPOSAL DOD Needs Better Resource Planning and Joint Guidance to Manage the Capability GAO-13-385 April 2013 EXPLOSIVE ORDNANCE DISPOSAL DOD Needs Better Resource Planning and Joint Guidance to Manage the Capability Highlights of GAO-13-385, a report to congressional committees Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found DOD has relied heavily on the critical skills and capabilities of EOD forces to counter the threat from improvised explosive devices on battlefields in Iraq and Afghanistan. The House Armed Services Committee directed DOD to submit a report on EOD force structure planning and directed GAO to review DOD’s force structure plan. DOD’s report provided little detail. GAO examined to what extent (1) DOD and the services have addressed increased demands for the EOD capability and identified funding to meet future requirements; and (2) DOD has developed guidance for employing the EOD capability effectively in joint operations. GAO evaluated DOD’s report and EOD guidance; analyzed data on EOD missions, personnel, and funding; and interviewed DOD and service officials to gain perspectives from EOD personnel and managers. Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) forces grew over the past 10 years to meet wartime and other needs, but the Department of Defense (DOD) does not have the data needed to develop a funding strategy to support future EOD force plans. To meet increased demands for EOD personnel, the services increased their EOD forces from about 3,600 personnel in 2002 to about 6,200 in 2012. Anticipating that the need for EOD will continue as forces withdraw from ongoing operations, the services intend to maintain their larger size. The Navy and Air Force have data on the baseline costs for some or all of their EOD activities, but the Army and Marine Corps do not have complete data on spending for EOD activities. Therefore, DOD does not have complete data on service spending on EOD activities needed to determine the costs of its current EOD capability and to provide a basis for future joint planning. Until all the services have complete information on spending, service and DOD leadership will be unable to effectively identify resource needs, weigh priorities, and assess budget trade-offs. EOD Active Duty Personnel Growth by Military Services, Fiscal Years 2002 through 2017 What GAO Recommends To better enable DOD to plan for funding EOD mission requirements and enhance future use of EOD forces in joint combat operations, GAO recommends that DOD direct (1) the Secretaries of the Army and the Navy to collect data on current Army and Marine Corps EOD funding, and (2) the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to develop joint EOD doctrine that would guide combatant commanders’ planning and clarify joint operational roles and responsibilities. In oral comments on a draft of this report, DOD concurred with the recommendations. View GAO-13-385. For more information, contact John Pendleton, 404-679-1816, or PendletonJ@gao.gov Figure Notes: Authorized personnel refers to the manning level the military services authorized for their EOD forces, as presented in service manning data. The Army and Air Force data above do not include EOD officers authorized prior to 2005 and 2008, respectively. EOD forces from all four services have worked together in Iraq and Afghanistan and the services have developed guidance on tactics and procedures for EOD forces, but challenges persist because DOD has not institutionalized joint EOD doctrine through a joint publication. Joint doctrine facilitates planning for operations and establishes a link between what must be accomplished and the capabilities for doing so. DOD studies have noted commanders’ limited awareness of EOD capabilities during combat operations, and EOD personnel reported challenges they attributed to non-EOD forces’ lack of understanding of EOD operations. Several DOD organizations have responsibilities for some EOD functions, but no entity has been designated as the focal point for joint EOD doctrine. Joint doctrine could help leaders identify EOD capability requirements and better position combatant commanders in their use of EOD forces in future operations. Joint doctrine that is developed and approved as authoritative guidance would enhance the EOD forces’ ability to operate in an effective manner, and would better position the services to identify capability gaps in meeting service, joint, and interagency requirements; to invest in priority needs; and to mitigate risks. United States Government Accountability Office Contents Letter 1 Background EOD Forces Grew to Meet Wartime and Other Demands, but DOD Does Not Have Data Needed to Develop Funding Strategy to Support Future EOD Force Plans EOD Forces Have Worked Together in Joint Operations, but DOD Has Not Developed Joint EOD Doctrine to Guide Effective Employment of the Capability Conclusions Recommendations for Executive Action Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 3 14 18 19 20 Appendix I Scope and Methodology 22 Appendix II Themes from the Group Discussions 30 Appendix III GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 33 Table 1: Composition of EOD Discussion Groups 27 6 Table Figures Figure 1: EOD Personnel Supporting a Range of Events Figure 2: Process for Becoming Certified as a Basic EOD Technician Figure 3: EOD Personnel Growth by Military Service, Fiscal Years 2002 through 2017 Figure 4: Example of Homemade Explosive Training Course and Mine Resistant Ambush-Protected Vehicle Page i 4 5 7 13 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal Abbreviations DOD EOD IED Department of Defense Explosive Ordnance Disposal Improvised Explosive Devices This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately. Page ii GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal United States Government Accountability Office Washington, DC 20548 April 25, 2013 Congressional Committees The Department of Defense (DOD) has relied heavily on the critical skills and capabilities of Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) personnel from each of the four military services to counter threats from improvised explosive devices (IED), a significant cause of fatalities among U.S. troops in Iraq and Afghanistan. 1 EOD personnel have extensive training in the detection, identification, on-site evaluation, making safe, recovery, and final disposal of unexploded explosive ordnance. EOD forces’ capabilities in countering the IED threat—including collecting and evaluating captured explosive-related enemy materiel from the devices— have made these forces integral to successful joint military operations. However, the high demand for the EOD capability has resulted in personnel experiencing numerous deployments. In addition to their function in countering IEDs, EOD personnel are responsible for a wide range of other missions, such as clearing unexploded ordnance from training ranges; providing defense support to civil authorities; and assisting the U.S. Secret Service and Department of State with the protection of the President and other high-ranking government officials. In House Report 112-78, which accompanied a House bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012, the House Armed Services Committee directed the Secretary of Defense to submit a report on Explosive Ordnance Disposal force structure planning to the congressional defense committees by March 1, 2012. 2 Further, the committee directed GAO to review DOD’s force structure plan and to report our findings to the congressional defense committees. 3 We 1 We have previously testified that IEDs accounted for almost 40 percent of the attacks on coalition forces in Iraq during 2008. See Warfighter Support: Challenges Confronting DOD's Ability to Coordinate and Oversee Its Counter-Improvised Explosive Devices Efforts, GAO-10-186T (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 29, 2009). Also, we have previously reported that approximately 16,500 IEDs were detonated or discovered being used against U.S. forces in Afghanistan in 2011. See Counter-Improvised Explosive Devices: Multiple DOD Organizations Are Developing Numerous Initiatives, GAO-12-861R (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 1, 2012). 2 See H.R. Rep. No. 112-78, at 116 (2011). 3 See id. at 117. Page 1 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal reviewed and evaluated the DOD report on EOD force structure directed by the committee, and in July 2012 we briefed the House Armed Services Committee staff on our observations of DOD’s force structure plan. We found that DOD’s classified one-page EOD report provided limited detail or context about the status of the department’s EOD force or plans for future EOD capability requirements. Also, we found that DOD had not established a new consolidated budget justification display that fully identified the services’ baseline EOD budgets, as directed by the House Armed Services Committee. 4 In order to provide additional information on the status of DOD’s EOD forces and identify baseline EOD budgets, we gathered and analyzed data on EOD forces’ support for joint operations and the services’ plans to support future EOD requirements. We reviewed and analyzed prior DOD reports on the EOD force, collected available data on personnel 5 and on budgets, and interviewed cognizant officials from the Office of the Secretary of Defense and the services. In addition, we conducted 28 group discussion sessions with EOD personnel to obtain their perspectives on the EOD capability. Specifically, we examined the extent to which (1) DOD and the services have addressed increased demands for the EOD capability and identified funding to meet anticipated future requirements; and (2) DOD has developed guidance for employing the EOD capability effectively in joint operations. To determine the extent to which DOD and the services have addressed increased demands for the EOD capability, we collected and analyzed data from each of the four services’ EOD forces, including data on the organizational structure of EOD forces; on the size of EOD forces since 2002; and on projected manpower needs. Further, we interviewed key DOD EOD officials across the department—including from the Office of the Secretary of Defense, each of the services, and various support commands—to gain their perspectives on the operational tempo of EOD forces; the use of joint EOD forces for recent EOD combat missions, and the challenges EOD forces experienced; and expected future EOD 4 The committee directed DOD to establish a new consolidated budget justification display that fully identifies the services’ baseline EOD budgets and encompasses all programs and activities of the EOD force for the functions of procurement; operation and maintenance; and research, development, testing, and evaluation. See id. at 116. 5 For the purposes of this report, we obtained data only for active duty EOD forces. These forces comprise the majority of EOD personnel. Page 2 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal mission requirements. To determine the extent to which DOD and the services have identified funding to resource EOD forces to meet anticipated future requirements, we collected and analyzed available EOD funding data from each of the services for the past 3 fiscal years. To determine the extent to which DOD has developed guidance for employing the EOD capability effectively in joint operations, we reviewed existing service, multi-service, and joint DOD regulations and doctrine; reviewed and analyzed prior DOD reports’ findings about doctrine; and determined whether associated recommendations had been implemented. We interviewed key DOD EOD officials to ascertain the extent to which DOD has comprehensive joint EOD guidance. Additionally, we met with officials from selected EOD units in all four military services and conducted group discussions with EOD-qualified team members, team leaders, senior enlisted personnel, and officers to obtain their perspectives on issues related to military service-specific missions, joint combat operations, training, equipment, and operational tempo. A more detailed description of our scope and methodology can be found in appendix I. We conducted this performance audit from May 2012 through April 2013 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. Background As depicted in figure 1 below, the services maintain highly trained EOD personnel responsible for eliminating explosive hazards in support of a range of events, from major combat operations and contingency operations overseas to range clearance to protecting designated persons, such as the President of the United States. The services’ EOD forces are dispersed worldwide to meet combatant commanders’ requirements. Units may be deployed together or organized into smaller teams, as missions require. EOD technicians generally work in two- or three-person teams to identify and disarm ordnance. Page 3 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal Figure 1: EOD Personnel Supporting a Range of Events Servicemembers volunteer 6 for the EOD force and attend joint basic EOD training at the Naval School Explosive Ordnance Disposal at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida. This 143-day course—staffed by Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps instructors—provides instruction in munitions identification, render-safe procedures, explosives safety, and EOD-unique equipment. Servicemembers who successfully complete training are certified as Basic EOD Technicians and, afterward, join their EOD units. This process is shown in figure 2 below. With additional training and experience, a Basic EOD Technician can earn advanced certifications as a Senior EOD Technician and a Master EOD Technician. 6 Enlisted personnel in the Army, Navy, and Air Force may volunteer for the EOD force during basic training. In the Marine Corps, enlisted personnel must have achieved an enlisted rank 4. Officer personnel in the Air Force and Army can volunteer to become EOD-qualified but are part of the Civil Engineer and Logistics career fields, respectively. In the Navy, officer personnel can join the EOD career field upon becoming a commissioned officer. In the Marine Corps, enlisted personnel who are EOD-qualified can become warrant or limited duty officers. Page 4 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal Figure 2: Process for Becoming Certified as a Basic EOD Technician The EOD capability is generally viewed as an activity that–comparable with logistics—supports combat forces, rather than as a combat activity. EOD forces in the Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps are considered support activities and are organizationally placed with other support forces. Examples of where EOD forces are organizationally aligned include the ordnance corps (Army), the engineer forces (Air Force and Marine Corps), and aviation forces (Marine Corps). Previous DOD studies have noted that this organizational alignment of EOD forces created operational challenges in recent operations. For example, one study noted that EOD forces, as support forces, were not perceived as available in some phases of a battle. In contrast with the other services, the Navy identifies its EOD force as a combat activity and it is organizationally placed within the Navy Expeditionary Combat Command. 7 According to Navy officials, this better reflects the battlefield role of its EOD force and provides advocacy at senior levels in the Navy. Other organizations have responsibilities for EOD activities and policy. Within the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations and Low Intensity Conflict serves as the Office of the Secretary of Defense proponent for EOD and is responsible 7 The Navy Expeditionary Combat Command mans, trains, and equips rapidly deployable and agile expeditionary forces to support warfare commanders’ requirements for maritime security operations around the globe. Page 5 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal for developing, coordinating, and overseeing the implementation of DOD policy for EOD technology and training. The Joint Staff’s Force Protection Division (J8 Directorate) oversees requirements from combatant commands related to the department’s EOD capability. The Secretary of the Navy is the DOD single manager for joint service EOD technology and training. 8 The Navy is supported in this role by a joint EOD Program Board made up of general or flag officers from each of the services who function as their respective services’ focal points for EOD program requirements. The Program Board establishes the joint EOD program and approves the plan and budget. The Technical Training Acceptance Board, under the Program Board, coordinates, approves, and standardizes all EOD common-type individual training. 9 The Program Board also has a role in prioritizing and recommending funding for research and development of equipment based on joint EOD requirements. EOD Forces Grew to Meet Wartime and Other Demands, but DOD Does Not Have Data Needed to Develop Funding Strategy to Support Future EOD Force Plans To meet increased demands for EOD personnel, the services increased the size of their EOD forces. Based on available data, we determined that the services grew from about 3,600 personnel in 2002 to about 6,200 in 2012—an almost 72 percent increase. The services anticipate that even as forces withdraw from recent operations the need for EOD forces will continue, so they intend to maintain their larger size. However, the respective services’ abilities to identify and track spending on EOD activities vary, so DOD does not have complete information on EOD spending. The House Armed Services Committee directed DOD to establish a consolidated budget justification display fully identifying the services’ baseline EOD budgets, but DOD has not done so. Without complete EOD spending information, the services and DOD may have difficulty in justifying the future EOD force structure, and in informing future funding plans and trade-offs among competing priorities. 8 See Department of Defense Directive 5160.62, Single Manager Responsibility for Military Explosive Ordnance Disposal Technology and Training (EODT&T), encl. 2, para. 3.a (June 3, 2011)(hereinafter cited as DODD 5160.62 (June 3, 2011)); see also Office of the Chief of Naval Operations Instruction 8027.6F, Naval Responsibilities for Explosive Ordnance Disposal, encl. 12 (Dec. 7, 2012). 9 Common-type training is defined as training in EOD procedures required by two or more military services in the normal execution of their assigned missions. See DODD 5160.62, Glossary (June 3, 2011). Page 6 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal Services Increased Numbers of EOD Personnel to Meet Demand for the Capability Over the past decade of military operations, the services all took actions to increase their EOD capabilities. As figure 3 shows, the Army more than doubled its EOD forces, with the largest increases occurring after fiscal year 2006. The Marine Corps and the Navy increased their EOD forces by approximately 77 percent and 20 percent, respectively. The Air Force increased its EOD forces by approximately 36 percent. 10 The services anticipate maintaining EOD personnel numbers at the 2012 level at least through the next 5 years, as is also shown in figure 3, although final decisions on EOD force size and structure will depend on future DOD budgets. According to DOD EOD officials, the time required to train qualified EOD personnel is lengthy; therefore, EOD is not a capability that can be built up quickly. Figure 3: EOD Personnel Growth by Military Service, Fiscal Years 2002 through 2017 Figure Notes: Authorized personnel refers to the manning level the military services authorized for their EOD forces, as presented in service manning data. The Army and Air Force data above do not 10 The Army and Air Force calculations presented above do not reflect data on authorized EOD officers prior to 2005 and 2008, respectively, because service officials could not provide these data. Page 7 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal include EOD officers authorized prior to 2005 and 2008, respectively, because service officials could not provide those numbers. Meeting the demands for EOD forces in combat operations has negatively affected EOD units’ personnel and ability to train for other missions. Each of the services met the combatant commanders’ high demand for EOD personnel by deploying EOD units and assuming risks as other EOD missions and training activities were left unfulfilled. For example, according to service officials, the services assumed some risks in some mission areas such as countering sea mines, clearing unexploded ordnance on training ranges, and providing defense support to civil authorities. EOD personnel who participated in our group discussions said they experienced multiple deployments and limited time at home, maintaining a pace that was exacerbated by time spent away from home in training and in support of the U.S. Secret Service and Department of State in the protection of important officials. 11 (Appendix II summarizes, in greater detail, the operational and personnel issues raised by EOD personnel who participated in group discussions we held.) As the services begin turning their focus away from training for deployments to Afghanistan to counter IEDs, officials from across the services and DOD officials noted that the services will need to retain the current EOD size so that they can expand training for their core missions and prepare for future requirements. For example, according to Navy officials, Navy EOD personnel will re-emphasize skills—such as diving— that are needed for their core missions. EOD forces will also be assigned to traditional missions to fill gaps in capabilities that came about when EOD forces were deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq. For example, according to DOD officials, EOD personnel will be available to combatant commanders for humanitarian demining, irregular warfare, and building international partner capacity activities. Also, according to Army officials, Army EOD forces will be available to respond more quickly to incidents involving unexploded military ordnance found in local communities. In addition, EOD forces will continue to provide support to the Very Important Persons Protection Support Activity’s mission of ensuring the safety of federal officials, such as the President, as they travel. In fiscal 11 The Very Important Persons Protection Support Activity provides EOD support to the U.S. Secret Service and the Department of State for the protection of high ranking government officials such as the President, Vice President, Secretary of State, and foreign heads of state visiting the United States. The services generally provide two-person EOD teams to search venues for explosive ordnance, among other duties. Page 8 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal year 2012, the services provided more than 473,000 hours of support to this activity; as a presidential election year, 2012 required greater than the annual average of about 300,000 hours provided from fiscal years 2007 through 2011. DOD officials expect EOD capabilities to continue to be in demand by combatant commanders for the foreseeable future. For example, officials believe that the IED threat is likely to persist given its low cost and high accessibility to non-state adversaries. In addition, based on the primary missions highlighted in DOD’s current strategic guidance, 12 the services anticipate continued requirements for EOD capabilities. For example, EOD capabilities are expected to be needed for several missions including, among others: (1) countering terrorism and irregular warfare; (2) countering anti-access/area denial measures, including mining; (3) countering weapons of mass destruction; and (4) providing support to civil authorities. The mission of countering anti-access/area denial measures, in particular, will require Navy EOD forces to train to counter anti-access measures that use sea mines and to clear explosive obstacles in sea lines of communication. Also, Air Force EOD forces will be expected to train to support recovery operations to keep air bases and runways clear of unexploded ordnance. All the services’ EOD forces will need to continue to train for homeland missions of providing support to civil authorities. In addition, EOD forces’ ability to conduct humanitarian demining activities can support combatant commanders’ efforts to help build relationships with other countries, according to DOD officials. Lack of Full Visibility into EOD Funding Complicates Planning for Resources to Meet Future Requirements DOD does not have the consolidated information on service spending on EOD activities needed to enable it to determine the amount of resources currently being devoted to EOD capabilities and how the services are planning to support joint EOD capability needs. The House Armed Services Committee directed DOD to establish a consolidated budget justification display that fully identifies the military services’ baseline EOD budgets and encompasses all programs and activities of the EOD force for specific functions. 13 Further, GAO’s Standards for Internal Control in 12 Department of Defense: Sustaining U.S. Global Leadership: Priorities for 21 Century Defense. January 2012. St 13 See H.R. Rep. No. 112-78, at 116 (2011). Page 9 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal the Federal Government 14 state that managers need financial data to determine whether they are meeting their accountability goals for effective and efficient use of resources. However, DOD has not taken steps to identify comprehensive financial data on EOD activities across the services, nor has it responded to direction by the House Armed Services Committee to establish a new consolidated budget justification display that fully identifies the services’ baseline EOD budgets and encompasses all programs and activities of the EOD force for the functions of procurement; operation and maintenance; and research, development, testing, and evaluation. According to an Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller) official, the DOD budget is not constructed or structured to report at the level of detail called for by the committee. In the absence of a departmental budget justification for EOD activities, we sought to compile DOD’s EOD spending but we were unable to collect comprehensive and reliable data because the completeness of the services’ EOD budget data varied. We requested funding data from all the services for EOD activities for fiscal years 2010 through 2012. According to the data the services provided, they received funding for EOD activities from their regular funding accounts for military personnel, for procurement, and for operation and maintenance. In addition, Congress has provided overseas contingency operations appropriations to the services for EOD activities. Further, the Joint IED Defeat Organization— which is largely funded by overseas contingency operations appropriations—paid for or provided some equipment, such as robots, and training, such as courses on the design and construction of IEDs. 15 However, we found that the Army and Marine Corps had incomplete or little available information but information from the Navy and Air Force was more complete. Specifically, we found the following: • The Army, which has the largest EOD force, does not have full visibility over EOD funding. Army officials collected some information on funding at our request, but they could not be sure that the data 14 GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO/AIMD 00-21.3.1 (Washington, D.C.: November 1999). 15 The mission of the Joint IED Defeat Organization is to lead, advocate, and coordinate all DOD actions in support of the combatant commanders’ and their respective joint task forces’ efforts to defeat IEDs as weapons of strategic influence. A primary role for the organization is to provide funding and assistance to rapidly develop, acquire, and field counter-IED solutions. Page 10 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal were complete and accurate. The Army regulation on EOD assigns responsibility for monitoring funding for the Army EOD program to the Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations, Plans, and Training (G-3/5/7). 16 Officials in that office, however, told us they do not have access to complete funding information because funding for EOD activities is spread across multiple programs, functions, or organizations. Officials who oversee the EOD program told us they would like to have funding data to assist in managing and prioritizing the Army’s EOD operations, but they have no plans currently to collect it. • The Marine Corps EOD program officials could readily provide us with procurement funding information, but not with comprehensive information on funding that could have come from other funding accounts, such as military personnel and operation and maintenance. • Officials in the office of the Navy EOD program resource sponsor could provide funding information because the Navy has a dedicated EOD program element code 17 and it tracks funding for the EOD capability separately on a continuous basis to enable it to manage its own capability. • Officials in the Air Force EOD program oversight organization could provide funding information on operating, maintaining, and procuring equipment and other items for the Air Force EOD force that it compiles and uses to manage the Air Force EOD program. However, it could not readily provide information on military personnel because, according to officials, personnel are accounted for across more than 30 program elements. Starting in fiscal year 2013, the Air Force began to use a dedicated EOD program element code to enable better identification of current EOD spending and to provide justification for the EOD capability in future budget requests. The services anticipate maintaining their currently authorized EOD personnel levels. 18 However, planning for the future EOD capability may 16 See Army Regulation 75-15, Policy for Explosive Ordnance Disposal (Feb. 22, 2005). 17 Program element codes are the building blocks of the defense programming and budgeting system, and can be aggregated to display total resources assigned to specific programs, or specific military services, or in other ways, for analytical purposes. 18 In this report, we use the term “authorized” to refer to manning levels for the EOD mission, as identified by the services. Page 11 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal be hampered by DOD’s lack of visibility into the current costs of EOD capabilities across the services. According to officials from each service, overseas contingency operations funding has been used to provide equipment and training to EOD forces for the past several years, such as that shown in figure 4 below. In the future these costs will have to be funded from regular appropriations, and to compete with other service priorities. 19 For example, the services received EOD robots and mine resistant ambush-protected vehicles from overseas contingency operations funding. Should EOD units need to continue to use the equipment in the future or to acquire similar such equipment, maintaining and procuring it may have to be funded through regular appropriations. Overseas contingency operations funding also provided advanced homemade explosive, forensic, and medical training opportunities that EOD technicians in our discussion groups thought were valuable to their missions and their safety. 19 We have previously reported that the Army and the Marine Corps quickly acquired and fielded equipment to meet evolving threats. The equipment was initially supported with overseas contingency operations funding rather than through the Army’s and Marine Corps’ regular budgets and was not listed on unit authorization documents (modified tables of organization and equipment for the Army and tables of equipment for the Marine Corps). See Force Structure: Army and Marine Corps Efforts to Review Nonstandard Equipment for Future Usefulness, GAO-12-532R (Washington, D.C.: May, 2012). Page 12 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal Figure 4: Example of Homemade Explosive Training Course and Mine Resistant Ambush-Protected Vehicle Service officials expressed concerns to us about the adequacy of future funding for their EOD forces after overseas contingency operations funding is phased out, but the extent to which the services have identifiable funding plans for future EOD activities varied. The Navy and Air Force now have program element codes that enable service officials to identify and evaluate the appropriate level of spending on their EOD capabilities. However, the Army’s and Marine Corps’ lack of complete data on the costs of their current EOD forces negatively affects their efforts to develop viable funding plans for supporting their EOD capability into the future. Until the services have information on current spending as well as justification for their future funding needs, service and DOD leadership will be unable to effectively identify resource needs, weigh priorities, and assess budget trade-offs within anticipated declining resources. Moreover, the lack of visibility into current spending and future funding plans may impede DOD’s ability to provide Congress with information needed to facilitate its oversight. Page 13 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal EOD Forces Have Worked Together in Joint Operations, but DOD Has Not Developed Joint EOD Doctrine to Guide Effective Employment of the Capability EOD forces have operated jointly in Iraq and Afghanistan to fulfill battlefield requirements, and the services have jointly developed guidance on tactics, techniques, and procedures for EOD forces, 20 but DOD has not fully institutionalized the guidance through joint EOD doctrine in the form of a Joint Publication. According to DOD, the purpose of joint doctrine is to enhance the operational effectiveness of U.S. joint forces. 21 It is written for those such as the services, among other recipients, who prepare and train forces for carrying out joint operations. Joint doctrine facilitates planning for and execution of operations, and it establishes a link between what must be accomplished and the capabilities for doing so by providing information on how joint forces can achieve military strategic and operational objectives in support of national strategic objectives. According to service EOD officials, joint doctrine also provides standardized terminology. EOD personnel and officials told us, however, that they had encountered repeated challenges—such as a lack of planning for EOD capabilities as well as variations among the services’ procedures—during joint combat operations. A key reason for the services’ challenges is the absence of a consistent understanding of EOD operations, including expectations for how forces should plan operations and work together. The services are disadvantaged with respect to EOD capabilities, knowledge, and use because DOD has not developed joint doctrine in the form of a Joint Publication. 20 See Multi-Service Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures for Explosive Ordnance Disposal, ATTP 4-32.16(FM 4-30.16) /MCRP 3-17.2C/ NTTP 3-02.5/ AFTTP 3-2.32 (Sept. 2011). 21 See Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Instruction 5120.02C, Joint Doctrine Development System, encl. A, para. 1.c (Jan. 13, 2012). Page 14 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal The Services Use Common EOD Operational Guidance, but Challenges Persist in Operating Jointly In 2001, DOD’s Air Land Sea Application Center 22 published multiservice guidance outlining a set of EOD tactics, techniques, and procedures for employing EOD forces jointly in a range of military operations. 23 The guidance, which was updated in 2005 and 2011, applies to leaders, planners, and EOD personnel and provides information that can help them understand each military service’s capabilities. The multi-service guidance, as updated, has been in place for more than a decade, but challenges in joint EOD combat operations have continued, as prior DOD studies on EOD capabilities have reported. One study described EOD forces’ efforts to work jointly as being “somewhat ad hoc” and noted that culture, technique, and language differences among the military services caused challenges in working together. 24 Another study reported on some combat unit commanders’ limited awareness of EOD capabilities during overseas combat operations. 25 For example, in some instances Army combat unit commanders did not understand the differences between the capabilities of EOD personnel who are trained to safely disarm ordnance and the capabilities of Army combat engineers, some of whom have limited training on disposing of select unexploded ordnance. As a result, some combat engineers, who are not trained to safely disarm ordnance, destroyed ordnance caches, resulting in improper handling of some of the ordnance caches and creating a more dangerous site containing debris as well as potentially unexploded ordnance. EOD personnel we spoke with reported experiencing similar challenges during recent deployments in support of joint combat operations, and as the observations recorded below indicate, they attributed these 22 The Air Land Sea Application Center is a multi-service organization established by the services’ doctrine centers to develop tactical-level solutions to multi-service interoperability issues consistent with joint and service doctrine. 23 This guidance describes each military service’s EOD organizations, capabilities, equipment, doctrine, and training and provides joint EOD command and control options, as well as information for planning and conducting EOD operations in a joint environment. This guidance was updated in 2005 and 2011 to reflect EOD’s evolving role in military operations. 24 Department of Defense, Final Report of Assessment for Joint Explosive Ordnance Disposal. (Washington, D.C.: July 31, 2006). 25 Squires & Fulcher, LLC. Joint Explosive Ordnance Disposal Force Transformation Analysis. A report prepared for the Department of Defense. May 30, 2007. Page 15 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal challenges to a lack of understanding of EOD operations on the part of non-EOD forces. EOD personnel indicated the following: • • • Commanders of combat units did not always take into account differences among the military services’ EOD forces. For example, Marine Corps EOD personnel commented that their EOD standard operating procedures include conducting dismounted patrols, while at one time the Army’s EOD personnel were not allowed to dismount from vehicles to conduct EOD operations. These Marine Corps personnel stated that Marine Corps commanders were unsure how to work with Army EOD forces supporting Marine units. Similarly, Air Force personnel said they were not trained to dismount to search for explosives, as Marine Corps commanders expected them to be. Non-EOD personnel in combat units did not always understand EOD protocols or capabilities. For example, Army EOD personnel cited an instance in which a non-EOD officer at a forward operating base picked up post-blast fragments of an improvised explosive device at a blast site, thus disturbing the site and contaminating potential forensic evidence. Other examples include commanders not securing sites where unexploded improvised explosive devices were found, and non-EOD personnel tampering with unexploded devices in an attempt to deactivate them before EOD personnel arrived. Requests for EOD support did not always take into account differences in how the various services’ EOD forces are organized. For example, an Army EOD Company contains approximately 40 people, while a Navy EOD Mobile Platoon has 8 people. According to Navy EOD personnel, battlefield commanders they supported sometimes received a smaller EOD force than was needed and expected, or conversely, sometimes received a larger force, which would require more logistical support than planned. We found that pertinent Navy and Air Force regulations only briefly mention joint EOD operations, and they refer to the multi-service guidance as a source for more detailed information. However, the Army’s and Marine Corps’ regulations do not discuss joint EOD operations in detail or refer to the multi-service guidance. A DOD study assessing the joint EOD capability reported that this multi-service guidance was not widely used by combatant commands. 26 In addition, according to DOD officials, this multi-service guidance is not as authoritative to the services 26 Department of Defense, Final Report of Assessment for Joint Explosive Ordnance Disposal. (Washington, D.C.: July 31, 2006). Page 16 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal and combatant commands as a Joint Publication, and is generally not used by the services to develop force requirements. DOD Does Not Have Joint Doctrine in the Form of a Joint Publication to Provide Authoritative Doctrinal Guidance for Joint EOD Operations Prior DOD studies have highlighted the need for joint doctrine on EOD operations and noted that current guidance is insufficient, but the Joint Staff has not published joint doctrine for EOD operations. We found that several DOD doctrinal joint publications refer to EOD activities, but most references are limited, recognizing the need for EOD but not providing additional guidance as to how such capabilities should apply to operations. EOD is briefly mentioned or discussed in greater detail in 30 unclassified or for official use only doctrinal joint publications. For example, the role of EOD is briefly mentioned in joint doctrine about operations such as antiterrorism, foreign humanitarian assistance, and evacuating noncombatants. The EOD role is more fully discussed in joint doctrine about countering the improvised explosive device threat, joint engineer operations, and addressing obstacles—such as unexploded ordnance and sea mines—that could be encountered by joint forces in a range of military operations. According to a Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff manual on joint doctrine development, part of the development philosophy for joint doctrine is that it continues to evolve as the United States Armed Forces adapt to meet national security challenges. 27 However, none of these joint publications addresses the full range of EOD capabilities and potential activities. As previous assessments of DOD’s joint EOD capabilities have reported, the lack of joint EOD-specific doctrine limits EOD forces’ and planners’ ability to identify and mitigate capability gaps. According to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff manual, joint doctrine projects must be formally sponsored by a service chief, a combatant commander, or a director of a Joint Staff directorate. 28 A key reason why joint EOD doctrine has not been developed is that no entity has been made accountable for following through on recommendations and sponsoring EOD doctrine, to include stakeholder coordination, for development of joint guidance. Although several organizations have responsibilities for some EOD functions, no one entity has been 27 See Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Manual 5120.01, Joint Doctrine Development Process, encl. B, para. 2 (Jan. 13, 2012). 28 Id. para. 5.a. Page 17 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal designated as the focal point on joint doctrine or operational issues. For example, the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations and Low Intensity Conflict, as the Office of the Secretary of Defense proponent for EOD, is charged with developing, coordinating, and overseeing the implementation of DOD policy for EOD technology and training, but that official is not involved with oversight of joint doctrine or operational issues. Similarly, the joint EOD Program Board, chaired by a flag officer designated by the Secretary of the Navy and comprising general officer representation from the other services, is generally focused on joint common EOD technology and training issues. One DOD EOD study, which according to a Joint Staff official was initiated by a former Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, recommended among other things that the Joint Staff sponsor the development of joint EOD doctrine. However, during DOD’s review process that recommendation was sent back to the Joint Staff for reconsideration, where, according to a Joint Staff official, the matter was dropped and never presented to senior leaders. Having joint guidance, such as joint doctrine, could put combatant commanders in a better position to make decisions about using EOD forces in future operations. In addition, joint EOD doctrine could provide a basis for planning and identifying capability requirements for future operations. Having joint doctrine that is developed and approved by the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff as authoritative guidance would enhance DOD’s EOD forces’ ability to operate in an effective manner and better position the military services to identify capability gaps in meeting service, joint, and interagency requirements; to invest in priority needs; and to mitigate risks. Conclusions As IEDs became a significant threat to U.S. forces in Iraq and Afghanistan, EOD emerged as a critical capability, and over the past decade, the services increased the size of their EOD forces. Growing the EOD capability takes time because of the highly technical training required and the additional experience needed to become proficient in handling dangerous unexploded ordnance. Looking toward the future, DOD and the services believe that broad demand for this capability will continue. Growth of the EOD forces until now has been funded in part by overseas contingency operations dollars, but these funds are likely to decrease as operations in Afghanistan diminish. A major challenge facing the EOD community, especially the Army and Marine Corps, is the lack of complete information to clearly show the resources it will take to sustain their larger force levels. Further, DOD does not have good visibility into Page 18 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal service spending on EOD forces. Without comprehensive information on the costs of the services’ EOD forces, senior service and DOD leaders are not well positioned to justify the current EOD force structure or to ensure that funding goes to priorities in accordance with strategic guidance. In addition, the absence of comprehensive information limits DOD’s ability to respond to congressional requests for budget information and may continue to hamper Congress’ oversight of the health and viability of the EOD force. Although EOD forces from each of the services have deployed together to support recent ground operations, attention to EOD as a joint capability has been limited. Differences among the services’ procedures complicate joint force planning and operations, and there is little common understanding of the EOD capability outside of the EOD force. The lack of understanding of EOD capabilities among those battlefield commanders has caused them challenges in providing the right capabilities to maximize the effectiveness of operations to protect U.S. forces and to collect information to defeat the networks of insurgents using IEDs against U.S. forces. A number of publications refer to EOD and its capabilities for specific functions, but none provides clear and complete guidance for integrating the activities of EOD forces with other combat activities and maximizing the capabilities that EOD forces provide. In addition, no entity has followed through on previous recommendations to sponsor and advocate for developing joint EOD doctrine. With joint doctrine that specifies the role of EOD in joint operations and provides a consistent lexicon for joint planning, EOD participation in joint operations could be more efficient and effective. In addition, with joint doctrine regarding future requirements for the joint EOD capability, the services will have more complete information to inform their force structure planning and provide adequately trained and experienced forces to meet future requirements. Recommendations for Executive Action We recommend that the Secretary of Defense take the following two actions: • • To improve the Army’s and Marine Corps’ ability to ensure adequate support of their EOD forces within expected budgets, direct the Secretaries of the Army and the Navy to collect data on costs associated with supporting their current EOD forces. To enhance the future employment of EOD forces in joint combat operations, direct the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to develop Page 19 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal joint EOD doctrine that would guide combatant commanders’ planning and clarify joint operational roles and responsibilities. Agency Comments and Our Evaluation We provided a draft of this report to the Secretary of Defense for comment. An official from the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations and Low Intensity Conflict provided oral comments on the draft indicating that DOD concurred with our report and both of our recommendations. We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees. We are also sending copies to the Secretary of Defense; the Secretaries of the Army, Navy, and Air Force; the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff; the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations and Low Intensity Conflict; the Commandant of the Marine Corps; and the Director of the Joint Improvised Explosive Device Defeat Organization. This report will also be available at no charge on our website at http://www.gao.gov. If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me on (404) 679-1816 or PendletonJ@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made major contributions to this report are listed in appendix III. John H. Pendleton Director Defense Capabilities and Management Page 20 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal List of Committees The Honorable Carl Levin Chairman The Honorable James Inhofe Ranking Member Committee on Armed Services United States Senate The Honorable Dick Durbin Chairman The Honorable Thad Cochran Ranking Member Subcommittee on Defense Committee on Appropriations United States Senate The Honorable Howard P. “Buck” McKeon Chairman The Honorable Adam Smith Ranking Member Committee on Armed Services House of Representatives The Honorable C.W. “Bill” Young Chairman The Honorable Pete Visclosky Ranking Member Subcommittee on Defense Committee on Appropriations House of Representatives Page 21 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal Appendix I: Scope and Methodology Appendix I: Scope and Methodology The scope of our review on Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) forces included the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the Joint Staff, and the military services, including select EOD units from each service, and other DOD organizations that utilized or impacted EOD forces. We obtained relevant documentation and interviewed key officials from the following offices: • • • • Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations and Low-Intensity Conflict; The Joint Staff • J34 – Deputy Directorate for Antiterrorism/Homeland Defense; • J5 – Strategic Plans and Policy Directorate; and • J8 – Force Structure, Resources, and Assessment Directorate; Department of the Army • Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff (Operations, Plans, and Training) EOD & Render Safe Procedures Branch; • U.S. Army Ordnance Corps Explosive Ordnance Disposal Directorate, Fort Lee, Virginia; • 20th Support Command, Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland; • 52nd Ordnance Group (EOD), Fort Campbell, Kentucky; • 49th EOD Company, Fort Campbell, Kentucky; • 723rd EOD Company, Fort Campbell, Kentucky; and • 788th EOD Company, Fort Campbell, Kentucky; Department of the Navy Navy • • Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, Navy Expeditionary Combat Requirements Branch; Navy Expeditionary Combat Command, Joint Expeditionary Base Little Creek-Fort Story, Virginia; • EOD Group One, Naval Amphibious Base Coronado, California; • EOD Mobile Unit One, Naval Base Point Loma, California, • EOD Mobile Unit Three, Naval Amphibious Base Coronado, California, • EOD Mobile Unit Eleven, Imperial Beach, California, • EOD Training and Evaluation Unit One, Naval Base Point Loma, California, • EOD Expeditionary Support Unit One, Naval Amphibious Base Coronado, California, and • Mobile Diving and Salvage Unit One, Naval Amphibious Base Coronado, California; Page 22 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal Appendix I: Scope and Methodology • • Executive Manager of EOD Technology and Training, Washington, D.C. • Naval EOD Technology Division, Naval Support Facility Indian Head, Maryland; • Naval School EOD, Eglin Air Force Base, Florida; Center for EOD and Diving, Naval Support Activity Panama City, Florida; Marine Corps EOD Occupational Field Sponsor, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps; • 1st EOD Company, Camp Pendleton, California; • 3rd EOD Company, Okinawa, Japan; and • EOD Personnel Supporting the 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing, Marine Corps Air Station Miramar, California; Department of the Air Force • EOD Program Directorate; • Air Force Civil Engineer Support Agency, Tyndall Air Force Base, Florida; • 96th Civil Engineering Squadron EOD Flight, Eglin Air Force Base, Florida; Joint Improvised Explosive Device (IED) Defeat Organization, Arlington, Virginia; and U.S. Northern Command Joint Force Headquarters, National Capitol Region, Joint EOD – Very Important Persons Protection Support Activity, Fort McNair, Washington, D.C. • • • • To determine the extent to which DOD and the services addressed increased demands for the EOD capability, we collected and analyzed data and descriptions from each of the four services’ EOD forces on their traditional military service EOD missions, including the total number of hours dedicated to support the Very Important Persons Protection Support Activity. After receiving the data showing the total number of hours dedicated to support this activity, we reviewed the data and interviewed the U.S. Northern Command official who provided them to assess the data’s reliability. Based on these actions, we determined that these data were sufficiently reliable to include the amount of hours of support EOD personnel provided to this activity. We also requested data on the organizational structure of EOD forces from each of the services; operational tempo of EOD units and the authorized numbers of EOD officers and enlisted personnel within each service from fiscal year 2002 through fiscal year 2012; as well as projected manpower needs through fiscal year 2017. After receiving the authorized EOD personnel data, as Page 23 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal Appendix I: Scope and Methodology identified by the services, we interviewed service officials who had provided it and other subject matter experts to assess the reliability of the data. Based on our review of the personnel data provided and our interviews, we determined that the personnel data were sufficiently reliable to describe growth in numbers of EOD personnel. Additionally, we interviewed key cognizant DOD officials with responsibility for EOD activities across the department—including from the Office of the Secretary of Defense, each of the military services, selected support commands, and units—to gain their perspectives on the operational tempo of EOD forces, use of joint EOD forces for recent EOD combat missions and challenges, and expected future EOD mission requirements. To determine the extent to which DOD and the services have identified funding to resource EOD forces to meet anticipated future requirements, we collected and analyzed available EOD funding data from each of the services for fiscal years 2010 through 2012. We requested that the services provide EOD funding data from the base and overseas contingency operations budgets for specific funding accounts, including military personnel; operation and maintenance; procurement; and research, development, test, and evaluation. Also, we requested that the services identify funding, if any, received from the Joint IED Defeat Organization, or other sources. The comprehensiveness of the data provided by each of the military services varied. After receiving the funding data, we interviewed service officials who had provided them to assess the reliability of the data. Based on our review of the funding data provided and our interviews, we determined that the funding data were incomplete, potentially inaccurate, and not sufficiently reliable to establish a baseline level of DOD’s EOD spending. To determine the extent to which DOD has developed guidance for employing the EOD capability effectively in joint operations, we systematically analyzed 75 unclassified and for official use only documents of existing joint DOD doctrine (Joint Publications) to identify the inclusion of EOD functions. One GAO analyst conducted this analysis, coding the information and entering it into a separate record, and another GAO analyst verified the information for accuracy. All disagreements were resolved by a third GAO analyst. The analysts then tallied the total number of joint DOD doctrinal documents in which EOD functions were included. In addition, we reviewed and analyzed prior DOD reports’ Page 24 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal Appendix I: Scope and Methodology findings about doctrine and examined whether associated recommendations had been implemented. Specifically, we reviewed an EOD report from the Joint Staff 1 and an EOD report analyzing transforming the joint EOD force. 2 We also reviewed guidance on EOD activities from the services, including multi-service tactics, techniques, and procedures guidance. Additionally, we interviewed key EOD officials across DOD to ascertain the extent to which DOD has comprehensive joint EOD guidance and, if so, any potential benefits joint guidance has provided. Moreover, we discussed with DOD and service officials how EOD has been integrated jointly across DOD in areas such as joint operations and the joint training and equipping of EOD forces. Finally, we met with EOD leadership and personnel from selected EOD units in all four military services and conducted 28 group discussions with EOD-qualified team members, team leaders, senior enlisted personnel, and officers to obtain their perspectives on issues related to military service-specific EOD missions, joint combat operations, training, equipment, and operational tempo. We used these data to provide illustrative examples throughout this report. A detailed discussion of how we conducted those group discussions follows, and more details of the themes from the group discussions can be found in appendix II. The group discussions included EOD-qualified personnel from the following military units: U.S. Army 52nd Ordnance Group (EOD), Fort Campbell, Kentucky • • • 49th EOD Company, Fort Campbell, Kentucky; 723rd EOD Company, Fort Campbell, Kentucky; and 788th EOD Company, Fort Campbell, Kentucky. U.S. Navy EOD Group One, Naval Amphibious Base Coronado, California 1 Department of Defense, Final Report of Assessment for Joint Explosive Ordnance Disposal. (Washington, D.C.: July 31, 2006). 2 Squires & Fulcher, LLC. Joint Explosive Ordnance Disposal Force Transformation Analysis. A report prepared for the Department of Defense. May 30, 2007. Page 25 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal Appendix I: Scope and Methodology • • • EOD Mobile Unit One, Naval Base Point Loma, California; EOD Mobile Unit Three, Naval Amphibious Base Coronado, California; and EOD Mobile Unit Eleven, Imperial Beach, California. U.S. Marine Corps • • • 1st EOD Company, Camp Pendleton, California; 3rd EOD Company, Okinawa, Japan; and EOD Personnel Supporting the 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing, Marine Corps Air Station Miramar, California. U.S. Air Force • 96th EOD Flight Civil Engineering Squadron EOD Flight, Eglin Air Force Base, Florida. We selected EOD units to visit based on information from the services for units that had recent deployment experience as well as the ability to provide sufficient quantities of EOD-qualified personnel who would be available to participate in our group discussions. Our overall objective in using the group discussion approach was to obtain insight and perspectives from EOD personnel on training, equipment, operational tempo, joint military operations, and military service-specific responsibilities. Group discussions, which are similar in nature and intent to focus groups, involve structured small group discussions designed to obtain in-depth information about specific issues. The information obtained is such that it cannot easily be obtained from a set of individual interviews. From each location, we requested that each military service provide up to 10 volunteers to participate in our group discussions. We also conducted group discussions separated by rank and position. Specifically, we conducted separate group discussions that were comprised of officers, senior enlisted personnel, team leaders, and team members. At one location, two group discussions included both officers and senior enlisted personnel, and two other group discussions included all available EOD personnel assigned to those particular units. The number of participants per group discussion ranged from 2 to 12. Discussions were held in a semi-structured manner, led by a moderator who followed a standardized list of questions. The group discussions were documented by one or two analysts at each location. Group discussions were conducted between August 2012 and October 2012. Page 26 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal Appendix I: Scope and Methodology Composition of the Discussion Groups We conducted 28 group discussions with EOD-qualified junior enlisted, noncommissioned officer, warrant officer, and commissioned officer personnel from the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force. During each discussion, we asked participants to complete a voluntary questionnaire that provided us with supplemental information about each person’s EOD background, including: • • • • • Rank; EOD qualification level (Basic, Senior, or Master Badge level); Number of deployments to Iraq or Afghanistan; Support provided to or received from another military service; and Support to the Very Important Persons Protection Support Activity. This information provided by participants helped us to ensure that we obtained a wide range of perspectives from qualified EOD personnel with a variety of EOD-related experiences. In total, we met with 188 EOD personnel. Table 1 below shows the composition of our various discussion groups. Table 1: Composition of EOD Discussion Groups Total number of participants completing the questionnaire Army Navy Marine Corps Air Force Total 39 53 67 29 188 Military Grade E-1 to E-3 5 0 0 2 7 E-4 to E-6 20 19 51 24 114 E-7 to E-9 7 16 9 3 35 a 8 a 1 15 W-1 to W-3 0 3 5 N/A W-4 to W-5 0 1 0 N/A O-1 to O-3 4 9 2 0 O-4 to O-6 3 5 0 0 8 No Response 0 0 0 0 0 Basic EOD Badge 25 10 37 10 82 Senior EOD Badge 8 11 17 4 40 Master EOD Badge 6 30 13 15 64 No Response/Not Applicable 0 0 0 0 2 EOD Qualification Level b Number of EOD Deployments in Support of Operation Iraqi Freedom None 28 19 39 7 93 1 to 5 deployments 11 34 28 21 94 Page 27 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal Appendix I: Scope and Methodology Army Navy Marine Corps Air Force Total 6 to 10 deployments 0 0 0 0 0 11 or more deployments 0 0 0 1 1 No Response 0 0 0 0 0 Number of EOD Deployments in Support of Operation Enduring Freedom None 21 14 28 5 68 1 to 5 deployments 18 39 39 24 120 6 to 10 deployments 0 0 0 0 0 11 or more deployments 0 0 0 0 0 No Response 0 0 0 0 0 Yes 26 46 50 25 147 No 13 7 17 4 41 Not Applicable 0 0 0 0 0 No Response 0 0 0 0 0 Yes 29 49 39 27 144 No 10 3 27 2 42 0 1 1 0 2 Received Support From/Gave Support to other Military Services Participated in Very Important Persons Protection Support Activity Missions No Response Source: GAO. a N/A stands for Not Applicable. There are no warrant officers in the Air Force. b Two participants identified their qualification level as “EOD Officer.” We performed content analysis of our group discussion sessions in order to identify the themes that emerged during the sessions and to summarize participant statements regarding EOD experiences and perceptions. Specifically, at the conclusion of all our group discussion sessions, we reviewed responses from the discussion groups and created a list of themes. We then reviewed the comments from each of the 28 group discussions and assigned comments to the appropriate themes. One GAO analyst conducted this analysis and a different GAO analyst checked the information for accuracy. Any discrepancies in the assignment of the comments to themes were resolved through discussion by the analysts. The information gathered during our group discussions with EOD personnel represents the responses of only the EOD enlisted and officer personnel present in our 28 group discussions and it is not projectable to other EOD personnel. We conducted this performance audit from May 2012 to April 2013 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Page 28 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal Appendix I: Scope and Methodology Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. Page 29 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal Appendix II: Themes from the Group Discussions Appendix II: Themes from the Group Discussions In group discussions, we asked EOD personnel for their perspectives on what is working well and what needs improvement with regard to military service-specific missions, joint combat operations, training, equipment, and operational tempo. We analyzed participants’ responses to identify the most common themes, which are summarized below. EOD Organizational Alignment and Career Path: Some participants from each military service raised concerns about where EOD is aligned within their respective military service. Some also noted issues with career paths for EOD-qualified officers. For example, Army, Marine Corps, and Air Force personnel expressed concerns about EOD alignment under the Ordnance Corps (Army) or Engineers (Marine Corps and Air Force). They perceived these alignments as hampering EOD forces’ influence for resourcing and operations. Additionally, Army officers reported that officer career paths are of concern because the EOD specialty is a technical area that is not the same as others in their organization. For example, the Army EOD officer career path is within the Logistics Branch of the Army, and all EOD officers are expected to have logistic skills; however, an Army officer noted that learning about managing fuel farms has nothing to do with EOD. Conversely, Navy participants viewed the officer career path as generally positive and noted that enabling an officer to stay within EOD for his or her entire career was beneficial to the EOD force. Training: Participants in the majority of the group discussions said they felt positive about the training they received, and almost all of our group discussion participants reported that they wanted more training or more time for training. Some group discussion participants reported concerns about not being able to train with the same types of equipment, such as robots, as they would be using when deployed. Both Army and Marine Corps personnel expressed the desire for more training in homemade explosives and casualty care. Additionally, Army and Navy personnel reported that they needed additional access to training ranges. Army participants at Fort Campbell noted that access to training ranges is difficult to provide because there are not enough training ranges for all EOD companies to train at their installation. Likewise, Navy personnel in the San Diego area noted that they have issues accessing training ranges, particularly for exercises involving demolition. Frequency of deployments: Participants in our discussions expressed mixed opinions regarding operational tempo. Some EOD personnel felt that the high pace of deployments and other missions put stress on EOD personnel and their families. For example, some personnel felt that EOD Page 30 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal Appendix II: Themes from the Group Discussions team leaders are getting burned out because they are always away from home. In addition, some personnel said that to cover missions clearing training ranges they had to turn down annual leave or cancel doctors’ appointments because of staffing shortages. Also, some personnel noted that during their 12 months home between overseas deployments they are often away from their families because of the need to attend training or sometimes to travel in support of the Very Important Persons Protection Support Activity. Some personnel liked a high operational tempo and voiced concerns about having too much down time as operational tempo slows. Support to Very Important Persons Protection Support Activity: Participants in many of our group discussions noted that the time they spent in support of the Very Important Persons Protection Support Activity exacerbated their high operational tempo, and some raised the concern that these missions are not an effective use of EOD skills. EOD personnel reported that these missions had a negative effect on EOD personnel and their families by taking them away from home too often. Further, they noted that to support these missions they missed training for overseas missions. Moreover, some participants said that the Very Important Persons Protection Support Activity missions were not a good use of the EOD skill set or did not use EOD to its full potential because EOD personnel are asked only to identify potentially explosive hazards but are not allowed to disarm anything that is found. Funding for Training EOD Units: Some participants in our group discussions reported concerns about the adequacy of funding for EOD training. For example, some Army EOD personnel said that they sometimes had to buy materials needed for training aides, such as electrical tape and electronic parts. Moreover, Army and Marine Corps personnel reported that specialized training, such as post-blast analysis or homemade explosive courses, is expensive, which limits the number of people who can take the training. In particular, Marine Corps personnel expressed concerns that money for training might be scaled back in the future. Incentive and Special Duty Assignment Pays: Participants in our discussion groups noted that incentive pay, special duty assignment pay, and retention bonuses are important to EOD personnel, and that availability of such pays is a factor in retaining EOD personnel, but that availability of incentives varied across the military services. Some participants from the Marine Corps raised issues regarding incentive pay, special duty assignment pay, and retention bonuses. Marine Corps Page 31 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal Appendix II: Themes from the Group Discussions personnel stated that, unlike the other military services, the Marine Corps does not provide any additional pays or bonuses for EOD, and they felt that not receiving these types of pay like the other services constituted an issue of equity. Page 32 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal Appendix III: GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments Appendix III: GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments GAO Contact John Pendleton, (404) 679-1816 or PendletonJ@gao.gov Staff Acknowledgments In addition to the contact named above, Margaret G. Morgan, Assistant Director; Tarik Carter; Simon Hirschfeld; Shvetal Khanna; James Krustapentus; James E. Lloyd III; Michael Shaughnessy; Michael Silver; Amie Steele; Tristan T. To; Cheryl Weissman; and Sam Wilson made key contributions to this report. (351723) Page 33 GAO-13-385 Explosive Ordnance Disposal GAO’s Mission The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability. Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through GAO’s website (http://www.gao.gov). Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. To have GAO e-mail you a list of newly posted products, go to http://www.gao.gov and select “E-mail Updates.” Order by Phone The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, http://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm. Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077, or TDD (202) 512-2537. Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information. Connect with GAO Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, Twitter, and YouTube. Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or E-mail Updates. Listen to our Podcasts. Visit GAO on the web at www.gao.gov. To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs Contact: Website: http://www.gao.gov/fraudnet/fraudnet.htm E-mail: fraudnet@gao.gov Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7470 Congressional Relations Katherine Siggerud, Managing Director, siggerudk@gao.gov, (202) 5124400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548 Public Affairs Chuck Young, Managing Director, youngc1@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800 U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149 Washington, DC 20548 Please Print on Recycled Paper.