RUSSIA, CHINA, AND THE UNITED STATES IN CENTRAL ASIA: AND COOPERATION

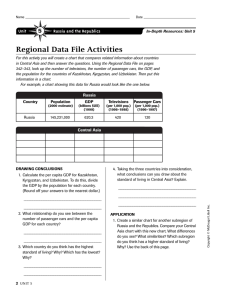

advertisement