Document 11039546

advertisement

LIBRARY

OF THE

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE

OF TECHNOLOGY

CHOICE OF THE ORGANIZATION

STRUCTURE-

A FRAMEWORK FOR QUANTITATIVE

ANALYSIS OF INDUSTRIAL

CENTRALIZATION/DECENTRALIZATION ISSUES

By

Peter Hammann

633-72

December 1972

MASSACHUSETTS

TECHNOLOGY

50 MEMORIAL DRIVE

BRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS

INSTITUTE OF

MASS. INST. TtCH.

FEB

DEWEY

10

1973

LIBKAi^Y

CHOICE OF THE ORGANIZATION STRUCTURE:

FRAMEWORK FOR QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS OF INDUSTRIAL

CENTRALIZATION/DECENTRALIZATION ISSUES

By

Peter Hammann

633-72

December 1972

Thanks are due to Jean Rutherford for kindly and meticulously typing the manuscript.

MAR 7

M.

I.

r.

1973

LIbKARIES

Abstract

Quantitative analysis of centralization/decentralization problems has

so far mainly centered around the question of how decentralization might be

achieved without departing from the system optimum,

techniques of linear and nonlinear models.

involving decomposition

Positive effects, besides

division of labour, of an application of the decentralization principle to

a

firm's organization were not taken into account.

decision model for

leading to

a

In order to do so,

a

hypothetical industrial organization has been developed,

a

comparison of the effectiveness of various more or less decen-

tralized organization structures.

budgeting, where management

performance through

a

is

heuristic routine.

by one or more evaluation criteria,

present achievement,

of the system.

The problem appears to be one in capital

required to generate information of sub-unit

System alternatives may be ranked

the one with highest rank, compared to

indicating steps toward desirable organizational change

For simplicity's sake,

the model,

in a first stage,

has been

conceived as static and deterministic.

This paper is partly based on the author's habilitation theses (14), submitted

to and accepted by the Department of Economics, University of Munich, July

1969 and February 1970, respectively.

Present research has been supported

and the Ford Foundation.

jointly by Technical University of Berlin

I.

What

II.

An overview of related work in Economics,

and Management Science

III.

Some definitions and statements

IV.

The model

is

the issue?

V.

Generation of return functions

VI.

Conclusions and outlook

Operations Research

The principle of task delegation or the division of labour is practically

as old as mankind.

What value can one, then, contribute to

a

quantitative

analysis conducted on the question "is delegation really worthwhile"?, if

generally an affirmative answer has been supposed to be unavoidable?

A

closer look at the problem, however, will reveal several ambiguous underlying assumptions and hazardous generalizations due to some rather one-sided

Let us examine briefly the main pitfalls,

considerations of basic facts.

which led to conclusions that seem to have lived too long, considering the

lack of empirical evidence:

1.

No clear distinction of tasks by their qualitative characteristics

has been made in this context,

thus dealing in an identical fashion with

such different tasks as filling out an order form and the decision on the

order quantity.

From the point of view of delegating task both these show

quite different implications due to quantitative dissimilarities and,

there-

fore, different effects with regard to responsibility for their completion.

2.

Delegation of task requires the evaluation of the various qualities

and capabilities of those person(s) with whom tasks will be shared.

these persons are incompetent,

disastrous.

Likewise,

If

task delegation might well prove to be

their ability to cooperate will enhance or reduce

the efficiency of the work of all concerned.

3.

Not an isolated analysis of the necessity to delegate task at some

particular hierarchical level

is

called for.

Problems of task delegation

can only be dealt with from the system's point of view in order to take

interdependencies of communication and information into account.

to delegate task in some specific way depends on the

The decision

ioint effort of all

-2-

individuals in the system.

is

The quality of

a

single individual's performance

irrelevant.

The various implications of delegation of management task,

especially

4.

decision-making,

have been studied from the system's point of view.

Howevei^,

analysis was conducted under the limiting assumption that the system

optimum

under centralization may not be violated.

Thus, positive effects of task

delegation, possibly leading to

a

higher system optimum were intentionally

neglected.

-

in this

Moreover, managpment

knowledge of the system's structure.

would seem to be quite unnecessary.

context

-

is

assumed to have perfect

Hence, delegation of decision-making

This sadly limiting view may have its

fatal origins in the desire to give some economic

interpretation to

a

well-

known algorithm for decomposing large optimization

models into a set of

sub-models so as to solve them more swiftly and elegantly.

In many analyses,

5.

delegated

is

control over units to which tasks have been

supposed to be exerted by prices, and/or goals and

quota setting.

Control by prices alone has been shown to be

ineffective (7), not least because markets for commodities and services do

not necessarily exist within

firm.

Whether this

structure itself.

is

a

so or not depends largely on the adopted

organizational

Especially, if decision-making

is

delegated,

interdependen-

cies of sub-unit decision processes may

generate "markets" in which outside

control (by central management)

However,

is

required to arrive at decisions at all.

the question remains, whether direct control

media such as prices,

goals or quotas will be accepted by the new

decision-makers.

Therefore, some

subtler indirect control methods or combinations

of direct and indirect methods

seem to be called for which, alas, have not

been investigated so far.

6.

Motivation of individuals to whom tasks have been

delegated

typically,

is,

taken to be granted or irrelevant, when

rigorous control methods

are applied centrally.

The latter may be true in some cases, but

the case

unfortunately, appears to be quite untypical.

itself,

Motivational methods,

therefore, will have to be taken into consideration, though it should be

realized that

-

from the point of quantitative analysis

effects of variations

in

information on the

these methods are extremely scarce.

Centralization of task,

7.

-

in

particular decision-making,

to generate economies of scale for a firm.

is

assumed

This need not be true.

It may

hold in cases of simultaneous central planning.

In

fact,

it

depends on the

completeness and accuracy of information at the central decision-maker's

The second point is that some sort of centralized decision-making

hands.

is

no issue at all for a particular firm.

if any

-

Therefore, economies of scale

-

will have to be achieved in other, more viable or appropriate organ-

ization structures.

8.

The conviction that economies of scale are generally at hand in

centralized systems has led to another conviction:

in such a

control must be exerted

way that these same economies are guaranteed, even when some

(necessary) delegation of task takes place.

Management, therefore, could be

tempted to fake decentralized decision procedures that, eventually, have no

value at all (see also (4) above).

The procedures are time consuming and

costly, possibly offsetting other benefits available.

Moreover, they are

too flimsy not to be understood by recipients of delegation who,

could try to cheat the central decision-maker.

Therefore,

it

in

turn,

seems to be

quite improbable that any real-life organization would work along these lines,

Let us summarize.

Traditional analysis has not centered around the

problem whether decentralization

take place and if so,

in

in

which way.

some particular form,

if ever,

should

Attention has been focussed instead on

the narrow and irrelevant issue, how some quas i-decentralization could be

effected without violating the system optimum.

As

this

is

always known to

management, decentralization appears to be initiated only when some "demo-

.

cratic soothing" of staff is appropriate.

The influences of information,

motivation and possible initiative of sub-unit decision-makers have been

completely ignored.

The task,

therefore, seems to be clear.

The problem

Given that viable alternatives exist, which

should be restated as follows:

organization structure (and hence the degree of decentralization) should

management choose if

it

wants to realize organizational change (see Bennis'

concept (6), pp. 59ff.) in

a

firm?

Finding an efficient, by no means supposedly

optimal, organizational structure for a new firm may be

it

a

second task.

However,

should be tackled, once the somewhat less bothersome first problem has been

We shall try to improve the mentioned defects of earlier

solved satisfactorily.

research by incorporating the notions of information, motivation and initiative

into the decision model.

However, this model should only act as

for more detailed research related to practical applications.

a

framework

At this stage,

we do not know enough about this many-sided problem so as to offer

a

thorough

solution

II.

For completeness' sake let us review very briefly relevant research don«

in

recent years from which one should start in dealing with problems of this

type.

The study that came nearest to the present one and (14) may well be the

one done by Thomas Marschak (28)

.

organizational structures by

time criterion for decision and communication

processes.

Marschak'

s

view,

a

thus,

interest as time considerations,

Tn

is

this he tried to evaluate alternative

a

partial one.

in most real

role when analyzing problems of this kind,

decision criterion.

It

is

of considerable

cases, will play an important

typically involving more than one

Decomposition theory

is

marked by such important papers as those of

Dantzig (10), Dantzig-Wolfe (11), Baumol-Fabian (5), Arrow (1), ArrowHurwicz (2), Charnes-Cooper (8), Charnes-S tedry (9) and Koopmans (20),

(21).

Extensions and discussions on various limitations of the Dantzig-Wolfe model

are given in Hass

who developed

a

(16), Charnes-Clower-Kortanek

(7),

Geoffrion (13), Balas (4)

different algorithm, Kronsio (24) and Ruefli (35).

In the

German literature H. Hax (17) has dealt extensively with the same problem.

Ruefli's paper is of considerable value as it offers

a

goal programming formu-

lation of the decomposition problem without recurring to a global objective

set for the system (which is the starting point in all other papers on

decomposition cited above).

Moreover, his analysis emphasizes the hitherto

ignored fact that the solution from the model, reached after

a

Sequence of

setting goals and prices, depends on the structure of the organization.

Though the well-known implications of goal programming (especially the setting

of goal weights)

limit Ruefli's approach, his results point into a direction

that further research might follow.

Kornai and Liptak (22),

(23)

have tackled decentralized decision-making

by the assumption that management or a central decision unit exert control

over sub-units in response to resource prices generated by the sub-units,

as

might be the case in centrally planned economies.

reformulating the problem as

a

The problem of optimizing

The solution is found by

game.

given organizational structure has been

a

Investigated by Hanssmann (15) as well as, more recently and

fashion, by Mueller-Hagedorn(31)

,

in a

more general

this being the lower-stage problem to the

one under review.

The interested reader is also referred to the ideas and suggestions of

J. Marschak(27),

Radner (33) and McGuire (30) on the theory of teams for the

sake of considering cooperative behavior of individuals in an

organization,

if required.

In

this context,

the system approach, at which this paper aims, has

been most forcefully stressed by Sengupta and Ackoff (36), revealing a

useful proposition on how to control a decentralized system.

Non-quantitative research has been conducted most extensively and the

literature on it

is

far too vast to be listed or commented on here.

Some

particularly relevant findings will be cited later at appropriate instances,

Centralization and decentralization of task are not absolute, but relative

categories.

If we are talking of "decentralization", we should bear in mind

that it is the degree of decentralization

(or centralization") which an organi-

zation has attained or is supposed to arrive at after organizational change

has taken place,

(See Albach

that matters.

(1),

p.

112).

Decentralization,

at least in this context, will be defined as the simultaneous delegation of

task and rights to decide on the task's best ways of accomplishment.

Koontz-O'Donnell (19), pp. 336

ff.). The

(See

primary question will not be how

decentralization may be effected but whether at all and to what degree it

should be realized.

It is clear that there cannot be a normative prescription

of particular organizational structures for firms

methodology aims at providing

a

in general.

The following

framework for individual evaluations.

We shall not deal in great detail with the in terdependencies of organization

structures and information system as has been done by Johnson,

Kast, and

Rosenzweig; (18? pp. 318ff.X Putnam, Barlow and Stilian (32, pp. llff.)or

Richards and Greenlaw (34, pp.

26 7ff-).

However,

there seems to be some

empirical evidence for the argument that an increase in quality and quantity

of information might entail a trend towards centralization of management task.

,

-7-

Let us review more closely the reasons claimed for some sort of decentralization in industrial organizations, as defined above.

on

lower hierarchical levels often stay in

problems than management mostly does,

a

It is because people

closer contact to concrete decision

that they might be given the rights to

decide on the task delegated to them in order to create:

greater sense of responsibility

-

a

-

better motivation

-

a

more intense commitment to their work.

This implies

a

division of labor and responsibility and should result in

-

hopefully, some initiative on behalf of the "new" decision-makers

-

possibly,

(e.g.,

new production, marketing and investment alternatives)

internal economies of scale.

They are facilitated through an increase in quantity and quality of in-

formation which is at the "new" decision-maker's disposal (viz.

more often

-

a

new or

-

improved way of planning) and reflects the closer contact he has

to a particular task.

The main reasoning for an increase in centralization

a

(or,

equivalently

decrease in decentralization), on the other hand, is the belief that the

quality of planning, coordination and control within the organization might

be brought about much more easily when a "central decision unit", whatever

that may be,

takes over or remains in charge.

Apart from that, one hopes

for economies of scale through more efficient resource allocation.

then, are all hypotheses,

is

in

both cases.

These,

What one should not do, however,

to claim for an a-priori empirical and/or theoretical evidence for preferring

one of these (in fact, many) alternatives

(see also, e.g.,

Ruefli (35), pp.

B-513f.).

If one sets out to "compare" different organization structures and

their related decision processes, human behavior emerges as the crucial

and, possibly, most sensitive

parameter

of all.

All human behavior, con-

sciously or subconsciously, appears to be motivated

by the kind or degree

of identification of human beings with their

environment.

far from new.

(See Simon

considered very carefully

to give

(37), p. XVI).

in

However,

this context.

In an

These facts are

they will have to be

industrial organization,

just one relevant example, members of the

central decision unit

will try to motivate subordinate decision-makers

quite deliberately.

is

This

done with respect to management goals and/or

decision alternatives by

means of

a

variety of compensation schemes bound to

accomplishment.

by its recipients.

other hand,

a

(See March-Simon

second time.

certain degree of

(26),

pp.

34f.

and pp. 52f).

On

the

central managment or decision unit should

not feel too confi-

dent about the outcome of this.

need not be,

a

This sort of motivation is certainly

perceived as such

Monetary and other incentives may be, but

taken up by the recipients or they iust work

once and fail the

There exists no such thing in an organization

as built-in

conformity or joint motivation of its members

that might be exploited to

the full when

the need arises.

(See,

e.g., McGregor's theory Y (28), pp. 45f).

Besides these very deliberate forms of exerted

and perceived motivation there

exists

such as

variety of motivational influences which,

typically, will

a

a

elude

organizational alternatives.

They are of

a

body

speculative nature and might best

be described by such homonyms as aspiration

and ambition.

E.g.,

the fact

that some particular task and rights to

decide on it are delegated to

person on

a

central decision unit which might be called

for to decide on viable

a

lower hierarchical level may constitute

(and

a

there is some

empirical evidence for that) some considerable

motivational force though its

impact may,

likewise, diminish again with time.

Analyzing the question

whether and to what degree decentralization

should take place

in an

organi-

zation will have to take such effects

into consideration even if their

-9-

causes may remain unknown, nebulous or vague and even if there may be no

way to influence or control them.

Control,

in

this study, will be effected by budgetary measures.

central management unit allocates

fixed budget to decentralized decision

Budgeting may not be the only way to control an organization.

units.

ever,

a

The

it is a

How-

typical one, which may be encountered in many industrial firms.

If we seek to compare structural alternatives we will have to ensure

comparison will be a reasonably "fair" one.

Introducing

a

that

a

fixed budget for

all the firm's operations in any organizational form may be regarded as

sufficient for the moment.

Thus,

the problem of evaluating more or less

decentralized organization systems appears to be

ing,

problem

a

in

capital budget-

the system alternatives being investment "portfolios" with uncertain

earnings streams.

In these "portfolios",

the decentralized decision-making

units, which themselves control a certain sub-system,

investment alternatives.

represent the various

From these remarks, then, it will be absolutely

clear that the problem at hand can only be solved from the system's point

of view.

Let us illustrate these ideas with the help of

a

simple model which

has been constructed to serve the purpose of demonstration of a methodology.

Let us assume that the firm manufactures

production departments (mtn)

difficulties.

.

m

products in

n

different

The products can be marketed and sold without

Product markets are tangent, but not overlapping.

The pre-

sent organization is such that separate departments for different product

groups have been formed, where all work is done.

Thus, no competition arises

•10-

for

A total budget

jointly needed capacities.

within and outside the firm.

Acquisition of raw materials and other produc-

tion factors shall be assumed as unconstrained.

immediately,

inventories will not build up.

reducing the problem to

a

limits all managerial actions

Its production will be sold

This assumption is a basic one,

An entirely different model would

static level.

have to be developed in order to take dynamic aspects into account.

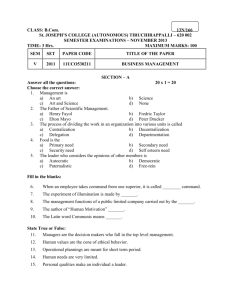

We are going to compare the following three organizational structures

(see the discussion in

for the decision process

1.

Centralized decison-making by

a

(38),

pp.

130f.):

central decision unit (simultaneous

planning; see Fig. 1).

2.

Decentralized decision-making in functional decision units such as

marketing and production (successive planning, as production decisions

are assumed to depend on prior marketing decisions; see Fig.

3.

2).

Decentralized decision-making in product divisions (simultaneous

planning; see Fig. 3).

A fourth alternative might be considered,

too:

decentralized decision-

making in product divisions with successive planning of marketing and production decisions.

We have left out this alternative somewhat arbitrarily

because coordination and control in organizations such as this seem to be

rather difficult to manage.

However, the list of alternatives could be

augmented without violating the methodological principles which we set out

to demonstrate.

Alternatives

2

and

3

require a-priori management decisions on who

supposed to serve as decision-maker in the decentralized units.

to say,

on paper

the pertinent personnel assignments have to be effected

-

before an analysis can take place.

-

at least

However, it would be possible

to check the problem under consideration with alternative assignment

schedules.

As will be seen,

is

That is

this might prove to be very costly because

-12-

CENTRAL MANAGEMENT

E

Division

Marketing

FINANCE

Division

1

Producti

Marketing

2

Producti

Division

Marketing

control flow

information flow

Fi£^_3:

Divisionally Decentralized Organization Structure

n

Producti

•13-

nearly all of the heuristic routines would have to be repeated many times.

As decision criterion we shall adopt profit or,

to profit generated by the system.

If we restrict ourselves

Probably, Marschak'

stage of the analysis.

,

contribution

to one criterion only we do so because information

on other pertinent criteria is too sketchy as

Whether it represents

applied next.

equivalently

Other criteria might be considered, too.

a

s

to be conclusive at this early

time criterion would be the one

system goal, is

a

matter of discussion.

For simplicity's sake, we shall assume linearity to hold in all functional

relationships.

on values

in

This can be defended,

certain limited ranges.

if variables are allowed only to take

We shall introduce several constraints

to this effect.

In detail, we shall assume that advertising through different media

the only marketing tool.

Market price will be held constant throughout.

firm is supposed to operate well below market saturation.

marketing instruments

is

is

The

Effectiveness of

considered to be discernible without lead time.

Production in the firm starts out from actual orders held over from previous

We shall not deal with problems of obsolescence of machinery, as

periods.

it does not add

significant aspects to the analysis.

It could easily be

integrated into the model if necessity to do so should arise.

Let us put together the model for the firs t alternative

to be a quite conventional mixed

be solved by standard methods

integer

.

It turns out

programming formulation which can

(such as the Brand and Bound Mixed Integer

Programming technique, used in (14) by the author for numerical examples).

Let

(in

vector notation):

p

=

commodity price

c

=

variable production costs per unit

b

=

production capacity

A

=

matrix of technical coefficients

X

=

production quantity

14-

W

=

advertising media quantity

V

=

matrix of advertising effectiveness coefficients

W* =

maximum advertising media quantity

k

=

advertising unit cost

q

=

held over order quantity (to be served according to the FIFO rule)

F

=

fixed cost of the system (independent of decisions)

q* = maximum production quantity

S

=

quantity of added machine aggregates

Z

=

unit capacity of added machine aggregates

g

=

unit cost of added machine aggregates

X

=

attrition cost rate of added machine aggregates

B

=

total budget of the firm (less fixed cost)

Then the objective function

be stated as

of the central

(and only) decision unit can

follows:

4.1 maximize Q^

4.2cx+gs+kw<B

4.3 x<q° + Uw

4.4 x>q

4.5 Ax<b + zs

4 6

.

w^ *

4.7 s<s>v

4.8 X

4.9

,s

s ,w

,w>o

integers

The model for the second alternative

far less detailed and "complete".

,

on the contrary,

two sub-units, one deciding on marketing activities,

operations.

appears to be

In this case, decisions are delegated to

the other on production

For both of these sectors, separate budgets are allocated through

the central decision unit where financial operations and control are retained.

•15-

It seems appropriate to postulate that the "new" decision-maker's should not

be recruited from the central unit's staff if the accent

formation and initiative by decentralized authorities.

members tend to have no better information as individuals.

initiative incorporated in model (4.1

-

4.9)

lies on better in-

Central decision unit

Moreover, the

their's anyway, most of the

is

As marketing decisions have to be observed by the production depart-

time.

Initiative, apart from better or more

ment, successive planning is necessary.

accurate information, may be brought about through the act of decentralizing

as such.

However,

this effect will fade with time.

As we are concerned with

system evaluation, we should suppose that central management will be willing

to implement organizational change

if this appears

to be "worthwhile".

It

may be worthwhile if the gains through decentralization (i.e., by stimulating

initiative) are big enough to offset possible future losses due to decaying

initiative (or, equivalently

,

increasing routine).

We will, at this stage,

not be concerned with the problem of maintaining and stimulating initiative

after organizational change has been carried through.

sight,

to be a

held apart:

limiting proposition.

However,

This may seem, at first

two stages should be clearly

the stage of organizational change and, what may be called,

the

"aftermath" stage.

The second stage will not be entered without having passed

through the first.

If

the a priori outlook for a transition

central management will not be tempted to move.

is

not good enough,

Therefore, we shall devote

research effort to the aftermath stage later on.

If we are

talking of initiative and its stimulation we should bear in

mind where it might be discerned if brought forward.

In our concept

the

following measures could possibly be taken by the new decision-makers:

-

Increasing advertising effectiveness through the creation of

new media or improvements on available media (change of lay-out

or messages).

Of course, an

increase in cost would be the

consequence which, however, might be offset by higher earnings.

Increasing manufacturing productivity through changes in production technology and/or initiation of economies on present

technologies.

Introduction of new products or product lines (if such initiatives

would not have to be checked with central management before taking

such steps).

Additions to machine capacity and similar expandatory measures.

As we have noted earlier, better and more detailed information might be

exploited,

This will lead to two, possibly intertwined, effects:

too.

A new decision-maker may view the decision problem the same way

as the central unit does.

However, parameters will take on dif-

ferent values.

A new

decision-maker has an entirely different view of the decision

problem's structure as compared to that taken by the central

management unit (e.g., differences

in

perception of the nature

of certain functional relationships").

From this follows that, contrary to the first of our alternatives, central

management will have only

performance.

Therefore,

a

limited and rather vague knowledge of sub-unit

it will be

forced to experiment on it or estimate

subjectively the possible outcomes of an organizational change.

Let us further assume that management tries to motivate sub-unit decision-

makers by means of some profit sharing.

in

this case:

a

Thus, we have two ways of motivation

monetary (i.e., profit sharing) and

the act of decentralizing as such).

non-monetary one (i.e.,

Monetary motivation through some sort of

profit sharing is quite common because it

and initiative motivation.

a

is

directed towards goal motivation

As we have noted earlier, however,

it

may not work.

But we shall adopt it as a first hypothesis on central management action.

The

17-

rate of profit shared with sub-unit decision-makers will be assumed to be

equal for all units throughout in order to exclude bargaining among them.

We are now in

a

position to formulate the models for the remaining two

decision alternatives.

Let us begin with functional decentralization

initiative in any of the two departments,

,

where

typically, will be counterchecked

by the other in not following up for some reason (see Enthoven's comment on

control of functionally decentralized systems (12), pp. 396ff.)'

Let

)

=

actual advertising expenditures

fr,(B„)

=

contribution to profit by the production department,

g*(B-.)

=

f

(B^

dependent on

optimum allocation of promotional expenditures

Therefore f^(By) should be replaced by the notation f„i|B„|

g''<-(B^ )

^

=

marketing and production budgets, respectively

B

=

total budget of the firm,

F

=

fixed system cost

C

=

vector of variable production costs per unit

q

=

vector of orders held over from earlier periods (to be

fh

=

profit share rate

B,

B„

identical to B in 4.2

served according to the Fifo rule)

cost factor) granted to sub-unit

(a

decision-makers

Then the objective function reads as follows:

4.10

4,

Maximize Q^

=

(1"

^

^

[

^

2

{

^^2

^''

I

''^l^l'

"

'^I'^'^l^

^Isubiect

cussion on how to obtain these

the moment.

We shall,

f unctions

experimentally or by estimation

instead, proceed to write down

tf^e

foi

model for the third

alternative (divisional decentralization), for which

we hold the important

(and no doubt,

limiting) assumption that the organization

of the firm may be

broken down into independent divisions.

Then let:

contribution to profit of division P (P = 1^--h)

"

^p^'^p-'

Cp

=

vector of variable costs per unit of division

q

=

vector of orders held over from earlier

periods in

p

P

division P (to be served according to the Fifo

rule)

The other symbols are retained from the model

for the second alternative.

Then the obiective function can be written as

follows:

H

4.14

Maximize Q

=

(i

-

/))-)

L

subject to

4.15

H

i

P

>

-

C q o

P P

As can be readily seen, models

f,

1'

Again,

P

P

1

4.17

common.

1

B

P =

4.16

I

P =

f^

(P =

1,---, H)

(P =

1,---, H)

(4.10

-

4.13) and (4.14

-

4.17)

h ave

much in

would have to be known for comparison of

alternatives,

Let us now turn to the important question

of how the unknown return functions

ot

and f

respectively, can be obtained.

There are, basically, two w..ys:

2,

p

f„

-

Experimentation

Estimation

19-

the situation faced by the central decision unit is a completely new

As

one no historical data will be available as a preliminary guideline.

Experimentation in both alternatives two and three means that return

functions would have to be established iteratively and heuristically

a

priori optimal allocation of the budget will be impossible.

An

.

For alternative

two one might proceed as follows:

Step

1:

Set budgets B, and B„ arbitrarily, however, observing restrictions

(4)

and

(12).

This could perhaps, also be done according to the

financial requirements of both departments in the last period,

which would have to be calculated post festum from secondary

historical data.

Transmit budget information to the marketing and production sub-

Step

2:

Step

3:

Step

4:

Transmission of optimal marketing plan to the production department.

Step

5:

Optimization of production goals.

unit decision-makers, selected previously.

Optimization of marketing goals.

At this stage we may distinguish

four cases:

(a)

B^

and B„ are fully used up.

(b)

B

is

fully used up, B„ only partly.

(c)

B.

is

only partly used up.

(d)

B,

and B„ are only partly used up.

B„ fully.

Therefore we have

Step

6:

Information of central management on total profit contribution

of the system and the financial status of the functional departments,

Central management may accept the arbitrary budget allocation as "optimal"

if

(a)

holds.

the firm

-

a

In case of

(d)

management should cut down the total budget of

very unlikely situation, however.

In cases

(b)

and (c)

a

re-alloca-

tion of budgets seems promising and central management might be tempted to do so.

Thus, one goes back to Step

if

1

and repeats the routine.

reallocations fail to bring additional gains,

or somewhere near to it.

times,

i.e.,

Iterations terminate

if we arrive at

(a)

It is possible to set budgets arbitrarily several

thus again obtaining points of the return function.

These we can

plot in both cases and a continuous curve may be fitted to the data, subsequently.

However, as these experiments will be rather costly, central man-

agement might be well advised to follow the above routine.

on

the other hand,

to perform some

during the first round.

It

is

It can be necessary,

iterations if one arrives at (a) already

important to keep in mind that the return

functions will constitute some much needed information for future planning

at

the aftermath stage.

Let us summarize the information flow in the system:

Central Management

Marketing

Production

Central

Management

Marketing

Production

±El1_±:

Total Advertising Expenditures

Marketing

Investment

Expendi tures

Total contribution

to Profit

Minus Attritions Costs

Total Variable Production Costs

Production

Investment

Expenditures

Information Flow in

a

Optimal

Marketing

Plan (Market

Constraints)

(Planning

Deadlocks)

Functionally Decentralized Organizati(

-21-

It should be noted that not all information emerging from the departments

will be transmitted to central management.

be necessary and sufficient.

The above information appears to

As the experiment shows some features of a real-

world business game some psychological implications should not be overlooked.

The designated sub-unit decision-makers may develop some routine when the

experiment is run too often.

Moreover, they may be tempted to fake initiative

and pretend to have better and more information than they actually do.

Hence,

the experiment will have to be handled very delicately in order to avoid any

such bias.

Much the same sort of reasoning applies to the generation of return

functions for alternative three

The process is simplified as there will be

.

simultaneous decision-making on production and marketing plans.

The steps

are now the following:

Step

1:

Set budgets B

In this case,

arbitrarily, observing constraints 4.15 and 4.16.

however, there will probably not be some sort of

advance or historical information on actual financial requirements in the divisions.

Transmit budget information to pre-selected division decision-

Step

2:

Step

3:

Optimization of division goals.

Step

4:

Information of central management on divisional profit contrib-

makers

.

ution and financial status.

As can be easily seen,

independence of divisions reduces the information

Again, central management may accept any

flow in the system to a minimum.

(more or less) arbitrary budget allocation as "optimal" if budgets are all

used up in the divisions.

One might stop repeating the experiment, possibly,

when results turn out iust to be

a

near miss of the "optimum".

In all other

cases, central management will be tempted to arrange budgetary shifts where

•22-

indicated to arrive at a different and, hopefully,

more auspicious budget

allocation.

Iterations terminate when no shifts are possible or

seem to

be called for.

The second way to arrive at sub-unit return

functions is, of course,

some form of subiective estimation

which could be helpful to

a

There may be a variety of "clutches"

.

manager seeking to arrive at reliable estimates.

Little (25) has offered some suggestions how to

do it which we can apply in

this context,

hand.

too,

if some knowledge of the system's past

performance

put of sub-units under budgeting.

at

The return functions will approach saturation

levels asymptotically as budget volumes increase

(Fig. 5).

b

Fl£^_5:

is

We may assume that some law of diminishing

returns holds for the out-

S

Idealized sub-unit response on return function,

.

.

.

-23-

This response or return curve may be determined by four points:

If budgets are reduced to zero,

During the preceding period,

there will be no returns (P^

the sub-unit

)

(under centralized

decision-making) put out f'(B') on the basis of

a

budget B*.

Central management, therefore, may hold the hypothesis that

a

similar performance should be expected under the adopted form

of decentralization

(P„)

Central management might ask for the necessary budget B if

increase in returns over f'(B') was to be achieved (P

507„

Central management will feel that there exists

level f*(B) which constitutes

a

a

a

)

saturation

maximum limit to sub-unit

output (P,).

Through the four points we can fit

a

smooth curve as in Fig.

5.

Algebraically, the curve would be of the following form:

5.1

=

f(B)

f-.v(B)

B^

2_^

•

oC

Where

+

B^

and r are constant parameters, reflecting central management's

'^^

expectations on the power and nature of decentralization response.

that for

B

=

0,

also

=

f(B)

Not(

0.

VI.

We have tried to provide

organizational choice.

a

framework for quantitative analysis of

The method has been shown with the help of three

distinct structural alternatives:

centralized decision-making

functionally decentralized decision-making

-

divisionally decentralized decision-making in contrast to earlier

:

.

•24-

research,

the following important notions have been considered in

the approach:

quality and quantity of information

motivation

initiative

on behalf of sub-unit decision makers.

allocation.

Control is exerted through budget

Point of view for the analysis has been the system.

As we have dealt primarily with methods,

not results from the analysis,

there may be room for a number of possible extensions.

Here is

a

list of

those which appear to be particularl/ fruitful for subsequent research and

applications

1.

Dynamic modelling of the problem.

To this purpose it might be

useful to delegate management task, but not decision-making.

Over

several periods, then, the system's behavior could be studied,

leading to a better understanding of work interaction at sub-

central levels.

With these results at hand,

a

decision of altering

the decision process might be better supported.

2.

Stochastic modelling of sub-unit response to management's motivational

methods

3.

Experimentation on the effects of other motivational methods than

4.

Study of the adaptive properties of control, possibly in conjunction

profit sharing and decentralization of authority.

with research done under position (1).

5.

Study of interactions

bet\.'een

divisions with regard to information

flow and resource bargaining.

6.

Investigations of initiative maintenance at the aftermath stage.

Methods that spring to mind, in this context, are management training

and post-experience studies.

-25-

7.

Improvements on experimental design for information gathering

sub-unit performance.

.

,

REFERENCES

1.

"Organisation" in:

Albach, H.

Band 8 (E. von Beckerath, ed )

Tuebingen 1964, pp. 111-117.

,

.

•

Handwoerterbuch der Sozialwissenschaf ten

Fischer, Stuttgart - J.CB. Mohr (Siebeck),

2.

Arrow, K. F., "Optimization, Decentralization, and Internal Pricing in

Contributions to Scientific Research in Management.

Business Firms" in:

University of California Press, Los Angeles 1959.

3.

Arrow, K.J. and Hurwicz, L., "Decentralization and Computation in Resou'-ce

Allocation" in:

Essays in Economics and Econometrics (R.W. Pf outs ed

The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 1960.

,

4.

5.

Balas, "An Infeasibility

in:

Operations Research

,

.

)

Pricing Decomposition Method for Linear Programs"

14 (1966), pp. 847-873.

Vol.

Baumol, W.F. and Fabian, T.

and External Economics" in:

,

"Decomposition, Pricing for Decentralization

Management Science Vol. 11 (1964), pp. 1-32.

,

6.

Bennis, W.G., "Theory and Method in Applying Behavioral Science to Planned

Organizational Change" in:

Operational Research in the Social Sciences

Tavistock Publications, London 1966. pp. 33-76.

(F.R. Lawrence, ed.).

7.

Charnes, A., Clower, R.W. and Kortanek, K.O., "Effective Control through Coherent

Decentralization with Preemptive Goals" in:

Econometrica Vol. 35 (1967),

pp. 294-320.

,

8.

Charnes A. and Cooper, W.W., Management Models and Industrial Applications

of Linear Programming.

John Wiley and Sons, New York 1961.

9.

Charnes A. and Stedry, A.C., "Search - Theoretic Models of Organization

Control by Budgeted Multiple Goals" in: Management Science Vol. 12 (1965),

pp. 457-482.

,

10.

Dantzig, G.B., Linear Programming and Extensions.

Press, Princeton 1963.

11.

Dantzig, G.B. and Wolfe, Ph., "Decomposition Principle for Linear Programs"

in:

Operations Research Vol. 8 (1963), pp. 101-111.

12.

Enthoven, A.C., "The Simple Mathematics of Maximization" in:

The Economics

of Defense in the Nuclear Age (C.J. Hitch and R.N. McKean)

Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass. 1965, pp. 361-405.

Princeton University

,

.

13.

Geoffrion, A.M., "Primal Resource - Directive Approaches for Optimizing

Nonlinear Decomposable Systems" in:

Operations Research Vol. 18 (1970),

.

pp.

14.

375-403.

Hammann, P., "Ein Entscheidungsmodell zur Beurteilung einer Zentralisation

Oder Dezentralisation von Entscheidungen"

Unpublished Habilitation Thesis,

University of Munich, July 1969 (publication forthcoming).

.

?7-

15.

"Die Optimierung der Organisationsstruktur" in:

Hanssmann, F.

fUr Betriebswirtschaft, Vol. 40 (1970), pp. 17f.

16.

Hass, J.E., "Transfer Pricing in a Decentralized Firm"

Science Vol. 14 (1968), pp. B310-B331.

Zeitschrift

,

in:

Management

,

17.

Hax, H.

Berlin

,

-

Die Koordination von Entscheidungen.

Bonn - Muenchen 1965.

Carl Heymans Verlag, Koeln

The Theory and Management

18.

Johnson, R.A., Kast, F.E. and Rosenzweig,

McGraw Hill, New York 1963.

of Systems.

19.

Koontz, H. and O'Donnell, C, Principles of Management.

York - Toronto - London 1964.

20.

Koopmans, T.C, "Analysis of Production as an Efficient Combination of

Activity Analysis of Production and Allocation (T.C

Resources" in:

John Wiley h Sons, New York 1951, pp. 33-94.

Koopmans, ed )

J.E.,

-

McGraw-Hill, New

.

.

21.

Koopmans, T.C, Three Essays on the State of Economic Science.

Hill, New York 1957.

22.

Kornai, J. and Liptak, T.

"A Mathematical Investigation of Some Economic

Effects of Profit Sharing in Socialist Firms" in:

Econometrica Vol. 30

(1962), pp. 140-161.

McGraw-

,

,

"Two-Level Planning" in:

Econometrica

23.

Kornai, J. and Liptak, T.

(1965), pp. 141-169.

24.

"Centralization and Decentralization of Decision-Making:

Kronsio, T.

The

Decomposition of Any Linear Programme in Primal and Dual Directions to

Obtain a Primal and a Dual Master Solved in Parallel and One or More

Common Subproblems" in:

Revue Francaise d' Informatique et de Recherche

Operationnelle Vol. 2 (1968), pp. 73-114.

,

Vol.

,

33

,

,

25.

The Concept of a Decision Calculus".

Little, J.D.C., "Models and Managers:

Working Paper 403-69, Alfred P. Sloan School of Management, M.I.T. Cambridge, Mass.

1969.

,

,

26.

March,

J.G.

and Simon, H.A., Organizations.

John Wiley ^ Sons, New York

1958.

27.

Marschak, J., "Elements of a Theory of Teams"

Vol. 1 (1955), pp. 127-137.

28.

Marschak, Th., "Centralization and Decentralization in Economic Organizations".

Technical Report No. 42, Department of Economics, Stanford University, Stanford, California, 1957.

29.

McGregor, D.M.

"The Human Side of Enterprise" in:

Leadership and

Motivation (D.M. McGregor; W.G. Bemis and E.H. Schein, eds.). The

M.I.T. Press, Cambridge, Mass. and London 1966, pp. 3-20.

30.

McGuire, C.B., "Some Team Models of a Sales Organization" in:

Science Vol. 7 (1961), pp. 101-130.

in:

Management Science

,

,

,

Management

•28-

31.

"Ein Ansatz zur Optimierung der Organisationsstruktur"

Mueller-Hagedorn, L.

Zeitschrift fuer Betriebswirtschaf t Vol. 41 (1971), pp. 705-716.

in:

32.

Putnam, A., Barlow, E.R. and Stilian, G.N.

Unified Operations Management.

A Practical Approach to the Total Systems Concept.

McGraw-Hill, New York

Toronto

London 1963.

,

,

,

-

33.

Radner, R.

"The Application of Linear Programming to Team Decision Problems"

Management Science Vol. 5 (1959), pp. 143-150.

in:

34.

Richards, M.D. and Greenlaw, P.S., Management Decision Making.

Homewood, Illinois, 1966.

35.

Ruefli, T.W., "A Generalized Goal Decomposition Model" in:

Science Vol. 17 (1971), pp. B305-B518.

,

,

R.D. Irwin,

Management

,

36.

Sengupta, S.S. and Ackoff, R.L., "Systems Theory from an Operations Research

Point of View" in:

IEEE Transactions, Vol. SSC-1 (1965), pp. 9-13.

37.

Simon, H.A., The New Science cf Management Decision-Making.

New York - Evans ton, 1960.

38.

Walker, A.M. and Lorsch, J.W.

"Organizational Choice:

Product versus

Function" in:

Harvard Business Review Vol. 46 (1968), pp. 129-138.

39.

Whinston, A., "Price Guides in Decentralized Organizations" in:

New

Perspectives in Organization Research (W.W. Cooper, A.F. Leavitt and

M.W. Shelly II, eds.).

John Wiley & Sons, New York - London - Sydney

1964, pp. 405-448.

Harper

&.

,

,

Row,

'H1^

Date Dui

Meat

\

APR 01

1991

T-J5

Fry,

143 w no.624- 72

Ronald Eu/Ttie accelerated

D^BKN

636659

3

TDflO

summer

0',lU''f}'f(!?

DQO ?bl

.,,

bfll

-72

DD3 b?D AT?

TDflD

3

HD28.M414 no.626- 72a

Zeno/The economic impact

Zannetos,

637016

n-BKJ

of

Q00277R2

fini ifiiilliiii

3

TOflO

HD28.IVI414

Sertel,

DDQ

3

no.629-72

Murat /The

637018.,.

357

7Mfl

fundamental

,0,

fill rM*'^r?

I

cont

TDflO ODM

bb? 3Ea

ri^'^^Mr'n

TQ6D QQD 7M7 ?bb

iiiiiiifri'iiT'iii

TDiBD DD3 7D1 TMD

..,.

3

TDflD

3

D03 h7D TEl

»4f.

liiliiiiii:iiiir]iii''iiiiiiiil

TDfiD

3

DD3 b71 Til

iiii5iiiiliiilii

3

3

TOaO DD3 7Q1 TbS

TDfiD

0D3 b7D

Tit.

-