Hazard (Edition No. 57) Autumn 2004 Victorian Injury Surveillance

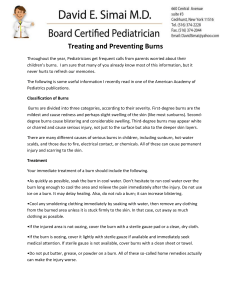

advertisement