Document 11035882

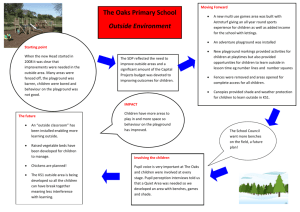

advertisement