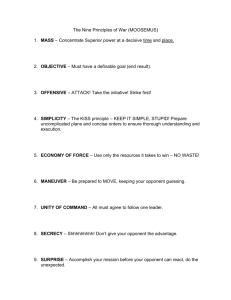

THE PRINCIPLES OF WAR IN THE 21ST CENTURY: STRATEGIC CONSIDERATIONS

advertisement