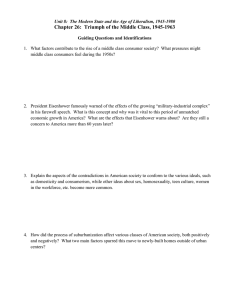

EISENHOWER AS STRATEGIST: Steven Metz February 1993

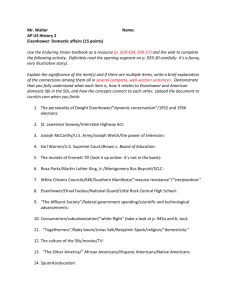

advertisement