Measuring Effectiveness and Value of Email Advertisements In Relationship–Oriented Email Messages

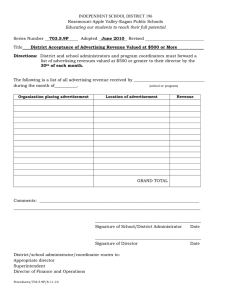

advertisement