L~- · Downtown Development as a By

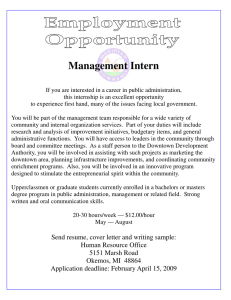

advertisement