Morphy Lake State Park New Mexico State Park Series Introduction and facilities

Morphy Lake State Park New Mexico State Park Series

Introduction and facilities

Morphy Lake State Park offers fishermen, campers, hikers, and other visitors a rustic alpine setting in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Spectacular views are the result of complex geologic processes active since Proterozoic time (1,700 m.y. ago): two major periods of mountain building (called orogenies) and most recently erosion and sedimentation by glaciers and rivers.

The state park is 7 mi southwest of Mora and 3 mi northwest of

Ledoux in the eastern Sangre de Cristo Mountains in northern

New Mexico (Fig. 1). It is the least accessible of the New Mexico state parks. From Ledoux on NM–94, the park is reached by a marked, 3-mi dirt road that can become impassable in bad weather. Four-wheel drive vehicles are recommended; trailers and lowclearance vehicles are discouraged. The park surrounds a lake that is 15–25 acres in size. An earthen dam was built in the late 1930s to enlarge the natural lake. An intake canal north of the dam (Figs.

2, 3) feeds the lake. An outlet tower at the southeast end of the dam allows for overflow into the creek that enters Rito Morphy.

The Sangre de Cristo Mountains and the Pecos Wilderness on the skyline rise to elevations in excess of 10,000 ft (Fig. 4).

Visitors to the lake enjoy boating (oars and electric motors only), camping, fishing, picnicking, hiking, and wildlife viewing.

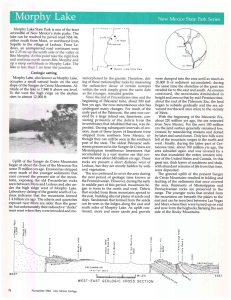

FIGURE 1—Location of Morphy Lake State Park.

Swimming is allowed, but there are no lifeguards, and the water is typically cold as the lake is at an elevation of 7,900 ft. Facilities at the state park are primitive; there are no showers, no telephone, no trashcans, no drinking water, and no electricity. The park has 60 campsites, a few picnic tables, and a paved boat ramp. Primitive

52

FIGURE 2—Facilities of Morphy Lake State Park.

N EW M EXICO G EOLOGY May 2002, Volume 24, Number 2

FIGURE 4—View looking west from the park toward Cebolla Peak in the

Sangre de Cristo Mountains, with Morphy Lake in the foreground. Rock ledges along the shore are sandstone of the Sandia Formation.

FIGURE 3—Intake canal for Morphy Lake in sandstone of the Sandia Formation.

FIGURE 5—Wildflowers along the shore of Morphy Lake.

toilet facilities are available. The New Mexico Department of

Game and Fish stocks the lake with rainbow trout, and native German brown trout also are common. Ice fishing is popular in winter. Ducks and geese can be found on the lake, and many other birds, including ravens, crows, blackbirds, and jays, frequent the state park. Squirrels, raccoons, porcupines, coyotes, deer, and black bear also wander through. Wildflowers dot the landscape after a rain (Fig. 5).

History

Prehistoric hunters and gatherers occupied this region as long as

9,000–10,000 yrs ago. Comanche and Apache Indians hunted deer and elk in the area. Spanish explorers passed through in the 1500s and 1600s; however, settlement did not begin until the early 1800s during the Spanish and subsequent Mexican occupation of the region. In 1816 a soldier named Antonio Olguin led some of the first settlers from Picuris into the area. The resulting settlement, located near Cleveland just north of Mora, was abandoned in 1832

(Kammer, 1992).

Morphy Lake State Park is part of the Mora Land Grant that was established in 1835 by Col. Albino Perez, Governor of the New

Mexico Territory of Mexico. The grant consists of 827,889 acres divided among some 75 grantees. The village of Mora was settled soon after. Comanche, Ute, and Apache Indians frequented the area until after the Civil War.

In 1851 Fort Union was established approximately 15 mi to the east of Mora and became a major stop on the Santa Fe Trail. One branch of the Santa Fe Trail passed through Mora, connecting it with Fort Union and Las Vegas (Simmons, 1986). Acequias or irrigation channels enhanced food production, and the Mora area became an important supplier of food and grazing land for Fort

Union, Las Vegas, and the surrounding area (Kammer, 1992;

McLemore, 1999).

French trappers settled the area south of Mora and founded

Ledoux. The original name of Ledoux was San Jose, but in 1902 when the post office was established, the name was changed to recognize the French guide and trapper Antoine Ledoux who settled in the area in 1844–1845 (Julyan, 1996). About 1892 a group of

Irish settlers founded the town of Cleveland, named after President Grover Cleveland, northeast of Morphy Lake (Anonymous,

1984).

The origin of the name of the lake is still a mystery; perhaps one of the Irish settlers named it (Young, 1984). Some maps spell the lake name Murphy. Farmers in the surrounding area first diverted water from the lake for irrigation about the turn of the century

(Kammer, 1992). The dam was constructed in the late 1930s in order to store more water. The Acequia de San Jose and Acequia de la Isla Associations of Ledoux originally leased Morphy Lake

State Park to the state in 1965; the Ledoux Water Association renewed the lease in 1990. Lake levels are maintained at a minimum of 15 acres for fish.

May 2002, Volume 24, Number 2 N EW M EXICO G EOLOGY 53

g •

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

• •

•

••

• • • •

• • • •

• • • •

• • • • •

• • • •

•

•

•

•

•

•

••

••

•

•

•

•••

••

•• •

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

••

• •

•

•

•

•

•

••

••

••

•

••

• •

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

• •

• •

•

•

• •

• •

• •

• •

•

•

••

•

••

• •

•• •

FIGURE 6—Geologic map of the Morphy Lake area (from Baltz and Myers, 1999).

Geology

The mountain forming the western skyline (Fig. 4) is Cebolla Peak

(elevation 11,879 ft) of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Most of the mountain range is composed of Proterozoic rocks of the Vadito and Hondo Groups, which consist of as much as 20,800 ft of mixed sedimentary and volcanic rocks that were subsequently metamorphosed (Fig. 6; Montgomery, 1963; Baltz and Meyers, 1999; Read et al., 1999; Williams et al., 1999). The Hondo Group, dominated by the Ortega Quartzite, is younger than the 1,720–1,700 m.y. old

Vadito Group that is exposed near Coyote Creek State Park approximately 20 mi to the northeast (Williams, 1990; McLemore,

1999). Deformation and metamorphism of the rocks probably occurred during several episodes between 1,650 and 1,400 m.y.

ago (Williams et al., 1999). These metamorphic rocks also are exposed along the dirt road from Ledoux to the state park. Eroded boulders and pebbles of multicolored white to gray to brown gneiss, schist, and quartzite from the Rincon Range to the north and the Sangre de Cristo Mountains to the west are found throughout the park. The Proterozoic rocks are similar to those forming El Oro Mountains east of Morphy Lake State Park, which consist of Proterozoic gneiss, muscovite schist, and amphibolites that are intruded by granitic pegmatites (Cepeda, 1972; Baltz and

O’Neill, 1984; Baltz and Myers, 1999). The metamorphic rocks were once sedimentary and volcanic rocks that were intruded by mafic sills (amphibolites) and granitic pegmatites. At least two periods of deformation and metamorphism occurred during the

Proterozoic, as evidenced by complex folds and regional doming and shearing.

The brown arkosic sandstone and conglomerate and interbedded gray shale found at Morphy Lake State Park belong to the

Pennsylvanian Sandia Formation, which was deposited about

320–315 m.y. ago in a deep marine basin called the Rowe–Mora

Basin (Fig. 6; Bachman, 1953). The Sandia Formation lies unconformably above the steeply dipping Proterozoic rocks (Baltz and

O’Neill, 1984; Baltz and Myers, 1999). The sandstone consists of quartz, feldspar, rock fragments, and mica derived from older Proterozoic metamorphic rocks. The shales are brown to black and

54 N EW M EXICO G EOLOGY May 2002, Volume 24, Number 2

vary in thickness. Brachiopod fossils (marine shelled animals) are found in thin limestone and shale beds south of the dam. In this area, most of the sediments in the Sandia Formation were shed from the Uncompahgre uplift to the west. Both the basin and the uplift formed at the same time as the Ancestral Rocky Mountains during the Pennsylvanian Period (330–290 m.y. ago). Subsequently, shallow seas retreated and returned several times during Permian through Cretaceous (65 m.y. ago) time. Only the oldest marine rocks of Pennsylvanian age are exposed at Morphy Lake; the younger sedimentary rocks have been eroded.

The rugged topography of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains that we see today on the western skyline is the result of a series of relatively recent geologic events. Starting about 70 m.y. ago during

Late Cretaceous–early Tertiary time, the region was subjected to a sequence of uplifting, faulting, folding, and tilting during a mountain-building event known as the Laramide orogeny. Evidence of this orogeny is visible to the east of the park, where the Rocky

Mountains meet the Great Plains along a dramatic zone of faults and folds. Major periods of erosion followed uplift, carving river valleys and forming alluvial fan and stream deposits along the eastern foothills and valleys of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, and depositing great thicknesses of alluvium over the Great Plains to the east.

More than 10,000 yrs ago during the wetter Pleistocene climate, small mountain glaciers developed on the mountain ridge. Glaciers are formed when fallen snow, over many years, compresses into large, thickened, slowly flowing ice masses. These alpine glaciers actually moved down the mountain a short way, similar to a slow river, and formed deep, bowl-shaped, steep-walled reentrants called cirques. Glaciers slowly erode the mountain, not by the ice, which is too soft to cut rocks, but by rock fragments embedded within the ice, which are effective cutting tools. The rock-choked ice grazes over the glacier bed, removing rock obstacles and leaving the bedrock rounded and smoothed. The depressions left behind by the glaciers later filled with water and formed

Pacheco, Santiago, and Enchanted Lakes in the Sangre de Cristo

Mountains. These three lakes, at an elevation of approximately

10,700–10,900 ft, mark the extent of downward movement by the alpine glaciers. As the climate warmed, the glaciers melted, and streams carved the mountain below the lakes and formed Morphy

Lake and Rito Morphy, which visitors cross just before entering

Morphy Lake State Park. The upper reaches of Rito Morphy consist of glacial boulders and pebbles that geologists call glacial outwash, whereas the lower parts consist of deposits of coarse- to medium-grained fluvial material.

Acknowledgments.

Special thanks to Joseph Griego, park manager, for information on the park history. Paul Bauer, Steve Cary,

Christy Comer, Greer Price, and Adam Read reviewed this manuscript. The NMBGMR cartography section drafted figures. Peter

Scholle, Director, New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral

Resources, is acknowledged for his support and encouragement of this project.

References

Anonymous, 1984, Morphy Lake State Park: New Mexico Geology, v. 6, no. 4, pp. 78–79.

Bachman, G. O., 1953, Geology of a part of northwestern Mora County, New

Mexico: U.S. Geological Survey, Oil and Gas Investigations Map OM–137, 1 sheet, scale 1 1 ⁄

4 inch to 1 mi.

Baltz, E. H., and Myers, D. A., 1999, Stratigraphic framework of upper Paleozoic rocks, southeastern Sangre de Cristo Mountains, New Mexico, with a section on speculations and implications for regional interpretation of Ancestral

Rocky Mountains paleotectonics: New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral

Resources, Memoir 48, 269 pp.

Baltz, E. H., and O’Neill, J. M., 1984, Geologic map and cross sections of the

Mora River area, Sangre de Cristo Mountains, Mora County, New Mexico:

U.S. Geological Survey, Miscellaneous Investigations Map I–1456, scale

1:24,000.

Cepeda, J. C., 1972, Geology of Precambrian rocks of the El Oro Mountains and vicinity, Mora County, New Mexico: Unpublished M.S. thesis, New Mexico

Institute of Mining and Technology, 63 pp.

Kammer, D., 1992, Report on the historical acequia systems of the upper Rio

Mora: New Mexico Historic Preservation Division, 96 pp.

Julyan, R., 1996, The place names of New Mexico: University of New Mexico

Press, Albuquerque, 385 pp.

McLemore, V. T., 1999, Coyote Creek State Park: New Mexico Geology, v. 21, no.

1, pp. 18–21.

Montgomery, A., 1963, Precambrian rocks; in Miller, J. P., Montgomery, A., and

Sutherland, P. K., Geology of part of the southern Sangre de Cristo Mountains, New Mexico: New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources,

Memoir 11, pp. 7–21.

Read, A. S., Karlstrom, K. E., Grambling, J. A., Bowring, S. A., Heizler, M., and

Daniel, C., 1999, A middle-crustal cross section from the Rincon Range, northern New Mexico—evidence for 1.68-Ga, pluton-influenced tectonism and 1.4-

Ga regional metamorphism: Rocky Mountain Geology, v. 34, pp. 67–91.

Simmons, M., 1986, Following the Santa Fe Trail: Ancient City Press, Inc., Santa

Fe, 214 pp.

Williams, M. L., 1990, Proterozoic geology of northern New Mexico: Recent advances and ongoing questions; in Bauer, P. W., Lucas, S. G., Mawer, C. K., and McIntosh, W. C. (eds.), Tectonic development of the southern Sangre de

Cristo Mountains, New Mexico: New Mexico Geological Society, Guidebook

41, pp. 151–159.

Williams, M. L., Karlstrom, K. E., Lanzirotti, A., Read, A. S., Bishop, J. L., Lombardi, C. E., Pedrick, J. N., and Wingsted, M. B., 1999, New Mexico middlecrustal cross sections: 1.65-Ga macroscopic geometry, 1.4-Ga thermal structure, and continued problems in understanding crustal evolution: Rocky

Mountain Geology, v. 34, pp. 53–66.

Young, J. V., 1984, The state parks of New Mexico: University of New Mexico

Press, Albuquerque, 160 pp.

—Virginia T. McLemore

May 2002, Volume 24, Number 2 N EW M EXICO G EOLOGY 55