Published By Science Journal of Environmental Engineering Research ISSN:2276-7495

advertisement

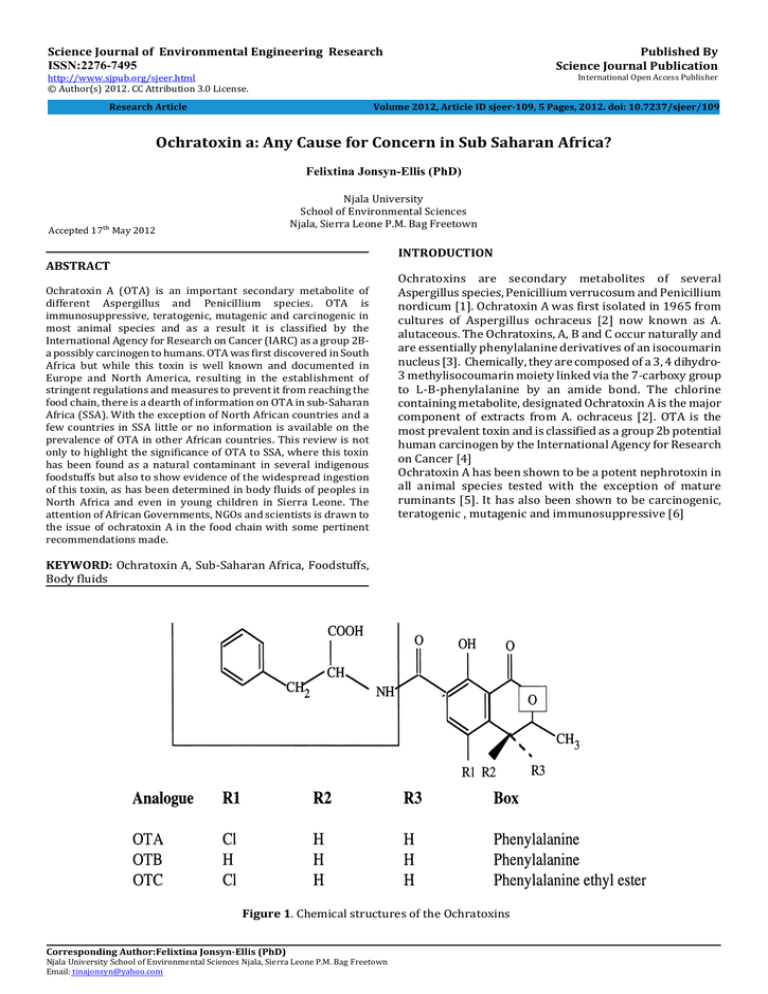

Published By Science Journal Publication Science Journal of Environmental Engineering Research ISSN:2276-7495 International Open Access Publisher http://www.sjpub.org/sjeer.html © Author(s) 2012. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Volume 2012, Article ID sjeer-109, 5 Pages, 2012. doi: 10.7237/sjeer/109 Research Article Ochratoxin a: Any Cause for Concern in Sub Saharan Africa? Felixtina Jonsyn-Ellis (PhD) Njala University School of Environmental Sciences Njala, Sierra Leone P.M. Bag Freetown Accepted 17�� May 2012 INTRODUCTION ABSTRACT Ochratoxin A (OTA) is an important secondary metabolite of different Aspergillus and Penicillium species. OTA is immunosuppressive, teratogenic, mutagenic and carcinogenic in most animal species and as a result it is classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as a group 2Ba possibly carcinogen to humans. OTA was first discovered in South Africa but while this toxin is well known and documented in Europe and North America, resulting in the establishment of stringent regulations and measures to prevent it from reaching the food chain, there is a dearth of information on OTA in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). With the exception of North African countries and a few countries in SSA little or no information is available on the prevalence of OTA in other African countries. This review is not only to highlight the significance of OTA to SSA, where this toxin has been found as a natural contaminant in several indigenous foodstuffs but also to show evidence of the widespread ingestion of this toxin, as has been determined in body fluids of peoples in North Africa and even in young children in Sierra Leone. The attention of African Governments, NGOs and scientists is drawn to the issue of ochratoxin A in the food chain with some pertinent recommendations made. Ochratoxins are secondary metabolites of several Aspergillus species, Penicillium verrucosum and Penicillium nordicum [1]. Ochratoxin A was first isolated in 1965 from cultures of Aspergillus ochraceus [2] now known as A. alutaceous. The Ochratoxins, A, B and C occur naturally and are essentially phenylalanine derivatives of an isocoumarin nucleus [3]. Chemically, they are composed of a 3, 4 dihydro3 methylisocoumarin moiety linked via the 7-carboxy group to L-B-phenylalanine by an amide bond. The chlorine containing metabolite, designated Ochratoxin A is the major component of extracts from A. ochraceus [2]. OTA is the most prevalent toxin and is classified as a group 2b potential human carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer [4] Ochratoxin A has been shown to be a potent nephrotoxin in all animal species tested with the exception of mature ruminants [5]. It has also been shown to be carcinogenic, teratogenic , mutagenic and immunosuppressive [6] KEYWORD: Ochratoxin A, Sub-Saharan Africa, Foodstuffs, Body fluids Figure 1. Chemical structures of the Ochratoxins Corresponding Author:Felixtina Jonsyn-Ellis (PhD) Njala University School of Environmental Sciences Njala, Sierra Leone P.M. Bag Freetown Email: tinajonsyn@yahoo.com Page 2 OCCURRENCE OF OCHRATOXIN A: Despite the acknowledged ubiquity of A. ochraceus, widespread across temperate and tropical regions, it is mostly referred to in the literature as occurring in temperate or continental climates [6] and as such its presence in Africa was not until recently fully recognized. Initially, the presence of OTA was mainly reported from European and North American Countries primarily in the wheat and barley growing areas [3] even though it was first discovered in South Africa [2]. Data related to the levels of OTA contamination in foods and feeds from tropical Africa is very limited. A. ochraceus has been found as a co-contaminant in a variety of foodstuffs examined in Sierra Leone, such as sesame seeds (beni seeds) maize, fermented cassava ("dry ball Foofoo") "ogiri" (fermented sesame seeds), broad beans, dried red pepper and smoke dried fish. Semi- quantitative analyses of these foodstuffs have shown that in most cases, OTA is present in appreciable quantities [7-10] In a preliminary survey of foods and feedstuffs from Senegal, Kane and colleagues [11] established levels of 34 ppb OTA in cowpeas. Aflatoxin was also detected in almost all samples, suggesting a competition between aflatoxin producing and Ochratoxin producing moulds [11]. In an earlier study in Nigeria, Adekunle and Ayeni [12] isolated A. ochraceus in most foodstuffs examined. In another study in Nigeria, even though A. ochraceus was not isolated in maize samples, OTA and Aflatoxin B1 were detected [13]. Recent studies on rice from Nigeria have shown the presence of OTA in 66.7% [14] and 98% [15] of rice samples from Lagos markets and Niger State respectively. There was also a wide gap in the levels detected in the two studies. Adejuyo and colleagues detected low levels of OTA (0.012.18 ng g-1) whereas Makum and colleagues detected levels as high as 134 - 341ug/kg. Cola nuts (Cola nitida) from Nigeria have been shown to contain OTA. Levels as high as 65.3ug/kg and 19.1ug/kg have been recorded in white and red cola nuts respectively [16]. The extensive exportation of coffee and cocoa beans to the European union, from tropical Africa, has necessitated a number of studies on the quality of these products .In one such study, it was determined that out of 162 samples of green coffee beans from different countries, the African samples were highly contaminated with OTA [17]. In North African countries where there is a prevalence of nephropathy and kidney problems, high levels of OTA has been detected in maize, rice, wheat and lentils [18-20] In South Africa, wine has been extensively studied for the presence of OTA. This toxin was detected in 15 white wines at level of >0.01 ug/l with a mean of 0.16ug/l and 9 red wines - mean 0.24ug/l [21]. OCHRATOXIN AND DISEASE Ochratoxicosis There are no reports in the literature of acute ochratoxicosis in humans. Ochratoxicosis appears to be well established disease entity in poultry and to a lesser extent in swine [22]. The immune suppressive nature [23] Anemia [24], nephropathy [25], teratogenicity [26] and carcinogenicity Science Journal of Environmental Engineering Research(ISSN:2276-7495) [27] of Ochratoxin A has been determined and documented in a number of animal species. OCCURRENCE OF OTA IN HUMANS Ochratoxin A is found in blood bound to serum albumin[28].. Low molecular weight species pass the glomerular membrane and accumulate in the kidneys and the highest concentrations of OTA are found in these tissues[29]. Ochratoxin A has a half-life of about 35 days in humans and since OTA binds readily to serum albumin, the blood concentrations are considered to represent a convenient biomarker of exposure [30] Several studies have been carried out in European countries and Canada, in order to examine human exposure to this toxin. OTA was detected in blood samples of healthy person at varying frequencies and levels [31] With the exception of some North African countries, comprehensive studies on ochratoxin levels in human body fluids, such as blood and urine samples. have only been conducted in Sierra Leone. Sangare-Tigori and colleagues [32] examined human sera in Abidjan, Ivory Coast for ochratoxin A. It was detected that 34.9% of healthy donors, had OTA concentrations ranging from 0.01 - 5.81 ug/l. whereas 20.5% nephropathy patients undergoing dialysis were OTA positive at levels of 0.167-2.42 ug/l. The nephrotoxic effect of ochratoxin A is detectable by urinary analysis, but this is relatively non-specific. Similarly, anaemia is an early manifestation but is also non-specific, and it is difficult to use this parameter for early diagnosis of the ailment. Ochratoxin A has been found in human milk samples in several European countries [31] Data on the presence of this toxin in Breast milk samples from Africa is very scarce. Two studies from Egypt [33, 34] have detected levels as high as 45ng/ml and 189ng/ml. Our study in Sierra Leone have shown considerably high levels - up to 337ng/ml in one sample [35]. OCHRATOXIN A AND HUMAN HEALTH Unlike aflatoxin which has been implicated in several diseases such as primary liver cancer, Reye's syndrome and Kwashiorkor, OTA has only been implicated in the aetiology of Balkan Endemic Nephropathy (BEN) and Urinary Tract Tumours (UTT). Endemic nephropathy is a fatal human renal disease, affecting predominantly rural populations in the central Balkan Peninsula. So far, the disease has been reported in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Romania, and Yugoslavia (Serbia)[36] Striking similarities between the changes in the renal structure and function found in endemic nephropathy and in ochratoxin A-induced porcine nephropathy suggested a common causal relationship. Epidemiological similarities, in particular the endemic occurrence support the hypothesis that ochratoxin A is a causative agent of endemic nephropathy in humans[37]. Even though ochratoxin was first discovered and documented by South African scientists [2], unlike aflatoxins there is a dearth in research relating to ochratoxin and human health in Africa. The association between the presence of OTA and nephropathy in Africa has been implied in only a few studies. With the exception of some North African Countries [18-20; 37, 38] and Senegal How to Cite this Article: Felixtina Jonsyn-Ellis , “Ochratoxin a: Any Cause for Concern in Sub Saharan Africa? ,”Science Journal of Environmental Engineering Research, Volume 2012, Article ID sjeer-109, 5 Pages, 2012. doi: 10.7237/sjeer/109 Science Journal of Environmental Engineering Research(ISSN:2276-7495 ) [11], very little information on disease related to OTA ingestion has been documented in other African countries. A high prevalence of nephropathy has been reported in Tunisia [18] and Algeria [19]. Recently, it has been reported that over two million young people of both genders are suffering from kidney problems (nephropathy) of unknown aetiology in Morocco [39] In Senegal, chronic renal failure accounted for 87.6% of all deaths from urogenital disease [11]. It was discovered that in countries were BEN is present; there was an unusually high prevalence of urinary tract tumours [40]. In the North African countries, in which human nephropathy similar to BEN is observed, the disease has been tentatively called chronic interstitial nephropathy (CIN) [40]. Like BEN, the causative role of ochratoxin A in CIN is very controversial. Results of two studies from Tunisian researchers [33, 42] have clearly indicated that there is causal uncertainty. It could be assumed that just like BEN, CIN could develop as a result of OTA acting synergistically with other environmental toxins. Wafa and colleagues [43] reported that levels of OTA were higher in a sample of Egyptians patients with urinary tract tumours -UTT than on healthy controls. The presence of OTA in breast milk, cord blood, serum, urine and stool samples from Africa, could predispose the kidneys to renal disease early in life. METABOLITES OF OCHRATOXIN A IN BODY FLUIDS Page 3 4R- Hydroxyochratoxin A (4R -OTA) has been detected in several studies of urine and stool specimens from infants and school children in Sierra Leone. While the parent toxin - OTA was only detected in 27% and 23% of urine samples of boys and girls during the rainy season, 4R -OTA was detected in 29% and 52% respectively, during this same period. Similarly, dry season samples contained OTA in 21 %( boys) and 31% (girls) and 4R -OTA in 37% (boys) and 38% (girls) [45]. Urine samples of 54 infants - 24 girls and 30 boys also showed that while the parent toxin was only detected in 3% and 33% (girls and boys) respectively, 4R -OTA was detected in 50% (girls) and 40% (boys) [46] Examination of stool specimens of 32 infants revealed the presence of OTA in 33% at concentration ranges of 0.114ng/ml and 4R -OTA in 46% at concentration ranges of 0.2-2.5ng/ml [46] Although 4R -OTA is considered less toxic than ochratoxin A [47] its presence in higher frequencies in urine and stool specimens examined is an indication of the presence of the parent toxin. Castegnaro and colleagues [48] however failed to detect this metabolite in human urine. One reason that could be advanced for the failure of detection of 4R -OTA was that their subjects suffered from Balkan Endemic Nephropathy with presumably damaged kidneys while subjects from Sierra Leone were young and had healthy kidneys capable of excreting the metabolite. Like Ochratoxin B which often co-occurs in foodstuffs, urine and stool specimens examined, 4R -OTA is believed to have an ameliorating effect on the toxicity of OTA [47] OTA is converted by cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes resulting in the production of 4R-OH-OTA and 4S OH-OTA [44]. Figure 2. Chemical structure of a derivative of OTA CONCLUSION: There is paucity of data on ochratoxin A in foodstuffs in African countries and even more importantly, data on dietary exposure through assessment of body fluids, is with the exception of North African countries and Sierra Leone, non-existent. Apart from the cocoa and/or coffee growing African countries which will ultimately be made aware of the presence and levels of OTA on these commodities by importing nations, such as EU countries, other African countries must endeavour to establish the prevalence and levels of OTA in local foodstuffs, particularly rice, which is a staple food in most communities along the West African nations. Rice is a very good substrate for colonization by A, ochraceus producing strains and is naturally contaminated by the spores of this fungus during storage [49] How to Cite this Article: Felixtina Jonsyn-Ellis , “Ochratoxin a: Any Cause for Concern in Sub Saharan Africa? ,”Science Journal of Environmental Engineering Research, Volume 2012, Article ID sjeer-109, 5 Pages, 2012. doi: 10.7237/sjeer/109 Page 4 Despite the fact that the role of OTA as the causative agent of human diseases such as BEN is not well defined, nonetheless extensive experiments on animals have provided conclusive evidence of its nephrotoxicity, carcinogenicity, teratogenicity and immunosuppressive nature. As OTA is now classified as a 2B carcinogen (possible carcinogen-according to IARC) - it is therefore imperative for African Countries to empower their scientists to: Ÿ Conduct studies to determine the occurrence and ecology of ochratoxigenic fungi and toxins in local as well as imported foods such as rice Ÿ Carry out epidemiological investigation to determine the extent of human exposure to OTA and document cases of chronic renal diseases Ÿ Understand and appreciate the gravity of mycotoxin (ochratoxin, aflatoxin and fumonisin) in the food chain and conduct massive awareness campaign. Ÿ Create a National Mycotoxin Awareness Study Network, similar to the one is Nigeria; in order to forge a North -South and South-South network to (a) standardize methods of surveys and determination of these mycotoxins (b) establish regulations and guidelines on specific mycotoxins (c) conduct collaborative research and (d) promote capacity building. Ÿ Search for local foodstuffs with antioxidant properties. Vitamin A, C & E are all known to have ameliorating effects on the toxicity of certain mycotoxins [50] Ÿ Investigate the effect of climate change on the production and accumulation not only of ochratoxin but all major mycotoxins. Ÿ With the full support and collaboration of the Ministry of Health, establish a Cancer Registry REFERENCES 1. Frisvad JC, Frank JM., Houbraken JAMP, Kuijpers AFA, Samson RA. New ochratoxin A producing species of Aspergillus section Circumdati. Stud. Mycol. 2004; 50: 23-43. 2. van der Merwe KJ, Steyn PS, Fourie L, Scott DB, Theron JJ. Ochratoxin A, a toxic metabolite produced by Aspergillus ochraceus Wilh. Nature 1965; 205(4976):1112. 3. Searcy JW, Davis ND, Diener UL. Biosynthesis of Ochratoxin A. Appl. Microbiol. 1969; 18,:622-627. 4. IARC. Some naturally occurring substances: Food items and constituents, heterocyclic aromatic amines and mycotoxins. In IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; World Health Organization: Lyon, France, 1993; Volume 56, pp. 489-521. Science Journal of Environmental Engineering Research(ISSN:2276-7495 ) 8. Jonsyn FE. Fungi associated with selected fermented foods in Sierra Leone. MIRCEN Journal 1989; 5: 457-462. 9. Jonsyn FE, Lahai GP. Mycotoxic flora and mycotoxins in smoke-dried fish from Sierra Leone. Die Nahrung 1992; 36: 485-489. 10. Jonsyn F E, Maxwell SM. Detection of ochratoxin A and aflatoxin in food samples from Sierra Leone. In Creppy EE, Castegnaro M, Dirheimer G. (editors): Human ochratoxicosis and its pathologies. Colleque INSERM 1993; 231 SUP. 11. Kane A, Diop N, Diack TS. Natural occurrence of ochratoxin A in food and feedstuffs in Senegal. In: Castegnaro M, Plestina R, Dirheimer G, Chernozemsky N, Bartsch H (editors): Mycotoxins, Nephropathy and Urinary Tract Tumors. IARC Scientific Pub. 1991; 115 Lyon International Agency for Research on Cancer 12. Adekunle AA, Ayeni, O. Occurrence and distribution of mycotoxic flora in some Nigerian foods. Egypt. J. Microbiol. 1974; 9: 85 -95. 13. Gbodi TA, Nwude N, Aliu YO, Ikediobi CO. The mycoflora and some mycotoxins found in maize (Zea mays) in the plateau state of Nigeria. Vet. Hum. Toxicol. 1986; 26: 1-5 14. Ayejuyo OO, Williams AB, Imafidon TF. Ochratoxin A Burdens in Rice from Lagos Markets. J. Env. Sci. and Tech. 2008; 1(2): 80-84 15. Makum HA, Dutton F, Njobeh P B, Mwanza M, Kabiru AY. Natural multi-occurrence of mycotoxins in rice from Niger State, Nigeria. Mycotoxin Research 2010; 27(2): 97-104 16. Dongo LN, Manjula K, Orisajo SB. Occurrence of ochratoxin A in Nigerian kola nuts. African Crop Science Conference Proceedings 2007; 8: 2133-2135 17. Romani S, Saccheti G, Lopez CC, Pinnavaia GG, Rosa M.D. Screening on the occurrence of ochratoxin A in green coffee beans of different origins and types. J. Agr. Fd. Chem. 2000; 48(8): 3616-3619. 18. Bacha H, Maaroufi K, Achour A, Hammami F, Blouze F, Creppy EE. Ochratoxicosis humaines en Tunisie. In : Creppy EE, Castegnaro M, Dirheimer G (editors) : Human ochratoxicosis and its pathologies. Colleque INSERM 1993; 231: 111-112 19. Khalef A, Zidane C, Charef A, Gharbi A, Tadjerouna M, Betbeder AM, Creppy. EE. In : Creppy EE, Castegnaro M, Dirheimer G (editors) : Human ochratoxicosis and its pathologies. Colleque INSERM 1993; 231: 123-127. 20. Filali A, Betbeder AM, Baudrimont I, Benayada A, Souleymani R, Creppy EE. Ochratoxin A in human plasma in Morocco: A preliminary survey. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2002; 21: 241-245. 5. Steyn PS, Holzapfel CW. The isolation of the methyl and ethyl esters of ochratoxin A and B, metabolites of Aspergillus ochraceus Wilh. J. S. Afr. Chem. Inst. 1967; 20: 186-189. 21. Shephard S, Fabiani A, Stockenstroem S, Mshicileli N, Sewram V. Quantitation of ochratoxin A in South African wines. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2003; 51 (4): 1102-1106 6. Kuiper-Goodman T. Risk assessment of ochratoxin A: an update. Food Addit. Contam. 1996; 13(Suppl):53-7. 7. Jonsyn F E. Seedborne fungi of sesame (Sesamum indicum L) in Sierra Leone and their potential aflatoxin/mycotoxin production. Mycopathologia 1988; 104: 123-1 22. Schaeffer J L, Hamilton PB. Occurrence and clinical manifestations of ochratoxicosis. In: Richard JL, Thurston JR (editors): Diagnosis of mycotoxicosis. 1986; Martinus Nijhoff, Dordrecht p. 43. How to Cite this Article: Felixtina Jonsyn-Ellis , “Ochratoxin a: Any Cause for Concern in Sub Saharan Africa? ,”Science Journal of Environmental Engineering Research, Volume 2012, Article ID sjeer-109, 5 Pages, 2012. doi: 10.7237/sjeer/109 Page 5 23. Dwivedi P, Burns RB. Effect of ochratoxin A on immunoglobulins in broiler chicks. Res. Vet. Sci. 1984; 36: 117-121. 24. Huff WE, Wyatt RD, Hamilton PB. Nephrotoxicity of dietary ochratoxin A in broiler chickens. Appl. Microbiol. 1975; 30: 48-51. Science Journal of Environmental Engineering Research(ISSN:2276-7495) 39. Zinedine A. Ochratoxin A in Moroccan Foods: Occurrence and Legislation. Toxins 2010; 2: 1121-1133 40. Pfohl-Leszkowicz A, Petkova-Bocharova T, Chernozemsky IN, Castegnaro M. Balkan endemic nephropathy and associated urinary tract tumours: a review on aetiological causes and the potential role of mycotoxins. Food Addit. Contam. 2002; 19: 282-302. 25. Krogh P. Mycotoxic porcine nephropathy: a possible model for Balkan endemic nephropathy. In: Puchlev A (editor) Endemic Nephropathy. Proceedings of the second International Symposium on Endemic Nephropathy. Bulgarian Academy of Science. Sofia 1974; pp. 266-270. 41. Filali A, Betbeder A.M, Baudrimont I, Benayad A, Soulaymani R, Creppy EE. Ochratoxin A in human plasma in Morocco: a preliminary survey. Human Exper. Toxicol. 2002; 21: 241245. 26. Rajendra D, Dwivedi P, Anil P, Sharma K. Critical period and minimum single oral dose of ochratoxin A for inducing developmental toxicity in pregnant Wister rats. Reprod. Toxicol. 2006; 22: 679-687 42. Grosso F, Saïd S, Mabrouk I, Fremy JM, Castegnaro M, Jemmali M, Dragacci S. New data on the occurrence of ochratoxin A in human sera from patients affected or not by renal diseases in Tunisia. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2003; 41: 1133-1140. 27. Bendele AM, Carlton WW, Krogh EB, Lillehoj EB. Ochratoxin A carcinogenesis in the (C57BL/&JXC?H) F1 mouse. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1985; 75(4: 733-742. 43. Wafa EW, Yahya RS, Sobh MA, Eraky I, El-Baz M, El- Gayar HAM, Betbeder AM, Creppy EE. Human ochratoxicosis and nephropathy in Egypt: A preliminary study. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 1998; 17: 124-129. 28. Galtier P. Contribution of pharmacokinetic studies to mycotoxicology- Ochratoxin A. Vet. Sci. Commun. 1978; 1: 349-358. 29. Stojkovic R, Hult K, Gamulin S, Plestina R. High affinity binding of ochratoxin A to plasma constituents. Biochem. Int. 1984; 9: 33-38. 30. Perry JL, Christensen T, Goldsmith MR, Toone EJ, Beratan DN, Simon JD. Binding of ochratoxin A to human serum albumin stabilized by a protein-ligand ion pair. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003; 107: 7884-7888. 31. OCHRATOXIN A (JECFA 47, 2001) www.inchem.org/documents/jecfa/jecmono/v47je04.htm 32. Sangare-Tigori B, Moukha S, Kouadio JH, Dano-Djedje S, Betbeder A-M, Achour A, Creppy EE. Ochratoxin A in human blood in Adidjan, Cote d'Ivoire. 2006; Toxicon. 47: 894-900 33. Abid S, Hassen W, Achour A, Skhiri H, Maaroufi K, Ellouz F, Creppy EE, Bacha H. Ochratoxin A and human chronic nephropathy in Tunisia: is the situation endemic? Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2003; 22: 77-84. 34. Hassan AM, Sheashaa HA, Fattah MF, Ibrahim AZ, Gaber OA, Sobh MA. Study of ochratoxin A as an environmental risk that causes renal injury in breast-fed Egyptian infants. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2006; 21(1): 102-105. 35. Jonsyn FE, Maxwell SM, Hendrickse RG. Ochratoxin A and aflatoxins in breast milk samples from Sierra Leone. Mycopathologia 1995; 131: 121-126 44. Omar RF, Gelboin HV, Rahimtula AD. Effect of cytochrome P450 induction on the metabolism and toxicity of ochratoxin A. Biochem. Pharm. 1996; 51(3):207-216. 45. Jonsyn-Ellis FE. Seasonal variation in exposure frequency and concentration levels of aflatoxins and ochratoxins in urine samples of boys and girls. Mycopathologia 2001; 152: 35-40 46. Jonsyn,FE. Intake of Aflatoxins and Ochratoxins by Infants in Sierra Leone: Possible Effects on the General Health of These Children. J. Nutr. Env. Med. 1999; 9: 15-22. 47. Stormer FC,. Hansen CE, Pedersen JI, Hvistendahl G, Aasen A.J. Formation of (4R) - and (4S) - 4-hydroxyochratoxin A from ochratoxin A by liver microsomes from various species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1981; 42: 1051 -1056. 48. Castegnaro M, Maru V, Petkova-Bocharova T, Nikolov I, Bartsch H. Concentrations of ochratoxin A in the urine of endemic nephropathy patients and controls in Bulgaria: Lack of detection of 4 hydroxyochratoxin A. IARC Sci Pub. 1991;115:165-169. 49. Park J W, Choi SY, Hwang HJ, Kim YB. Fungal mycoflora and mycotoxins in Korean polished rice destined for humans. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2005; 103:305-314. 50. Grosse Y, Chekir-Ghedira L, Huc A, Obrecht-Pflumio S, Dirheimer G, Bacha H, Pfohl-Leszkowicz A. Retinol, ascorbic acid and alpha-tocopherol prevent DNA Adduct formation in mice treated with the mycotoxin, ochratoxin A and Zearalenone. Cancer. Lett. 1997; 114: 225 - 229. 36. Krogh P. Epidemiology of mycotoxic porcine nephropathy. Nordisk Veternaermedicin. 1976; 28: 452-458 37. El-Sayed AM Abd Alla., Soher EA,. Neamat-Allah AA. Human Exposure to Mycotoxins in Egypt. Mycotoxin Res. 2002; 18: 23-30. 38. Zohair S, Salim A. A Study of Human Exposure to ochratoxin A in a Selected Population in Egypt. American-Eurasian J. Agric. & Environ. Sci. 2006; 1(1): 19 - 25 How to Cite this Article: Felixtina Jonsyn-Ellis , “Ochratoxin a: Any Cause for Concern in Sub Saharan Africa? ,”Science Journal of Environmental Engineering Research, Volume 2012, Article ID sjeer-109, 5 Pages, 2012. doi: 10.7237/sjeer/109