Is the Price Right? A study ... grocery shopping by Minnie Lau

advertisement

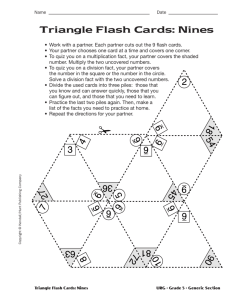

I Is the Price Right? A study of pricing effects in online grocery shopping by Minnie Lau Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Engineering in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY September 2000 @ 2000 Minnie M. Lau. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part, and to grant others the right to do so. A uthor . . . . ........... . ......................................... Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science June 7, 2000 Certified by. John D.C. Little Institute Professor Thesis Supervisor . Accepted by . . . . . . . Arthur C. Smith BARKER Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Theses MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUL 2 7 2000 LIBRARIES Is the Price Right? A study of pricing effects in online grocery shopping by Minnie Lau Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science on June 7, 2000, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Engineering in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Abstract This thesis explores the possibility that having a nine as the ending (the right most digit) of a price may increase or decrease product demand under different circumstances. An experiment simulating an on-line grocery shopping environment was designed to investigate this effect on grocery products. The findings yield significant evidence that pricing products with a nine ending will gain a sale advantage in certain situations, depending on the shoppers' budget limits and the nature of their shopping trips. Thesis Supervisor: John D.C. Little Title: Institute Professor 2 Acknowledgments Thanks are due to the following people whose assistance I could not have done without: " Professor John D.C. Little, for everything. " Robert Zeithammer, for help and guidance. " LaVerdes Owner and Manager, for providing sales information. " Friends, for believing and encouraging. " and of course my parents without whom MIT would not have been possible. 3 Contents 1 8 Introduction 1.1 Motivation for Studying Nine-Endings . . . . . . . . . . 9 1.2 Literature Review . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10 1.2.1 Underestimation of Actual Price . . . . . . . . . 10 1.2.2 Association of Meanings to Prices . . . . . . . . . 11 1.3 Current Nine-Ending Theories . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12 1.4 Modeling the Effect of Nine-Ending in Consumer Choice 13 15 2 Experimental Design . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15 2.3 Nine-Ending Phenomena to be Studied . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16 2.4 Overall Description . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18 2.5 Generation of Categories and Products . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19 2.6 Pricing Adjustment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22 2.7 Data Collection and Cleaning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22 2.8 Statistical Analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23 Statistical Properties of the Measured Difference in Shares . . 23 2.1 Objective 2.2 Nine-ending Effect Measuring Methodology. 2.8.1 3 25 Result Discussion 3.0.2 Hypothesis Testing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25 3.0.3 Main Nine-Ending Effect . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25 3.0.4 Fraction of Nines . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27 4 4 3.0.5 Ordering of Product A within a Choice Set . . . . . . . . . . . 28 3.0.6 Probability of Purchasing of the Two Budget Groups . . . . . 29 3.0.7 Budget Size . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29 3.0.8 Sequence of Choices during the Experiment . . . . . . . . . . 31 3.0.9 Budget Size and Sequence of Choices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32 33 Comments and Summary 4.1 Doing the Online Experiment in the Lab vs. Elsewhere . . . . . . . . 33 4.2 Using Hypothetical Products . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34 4.3 Future Research . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34 4.4 Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34 A Online Survey 36 B Web Experiment 38 C Categories and Products 47 D Figures 52 5 List of Figures B-i Login Page . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39 B-2 Scenario . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40 B-3 Bread Style - First part of a sample aisle . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41 B-4 Bread Choices - Second part of a sample aisle . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42 B-5 Tooth Paste Style - First part of a sample aisle . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43 B-6 Tooth Paste Choices - Second part of a sample aisle . . . . . . . . . . 44 B-7 Questionnaire - Personal Preference Sample Questions . . . . . . . . . 45 B-8 Questionnaire - Shopping Background . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46 D-1 Frequency Histograms of 25 Walk-ins . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53 D-2 Frequency Histograms of 493 Subjects 54 6 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . List of Tables 3.1 Main Nine Ending Effect . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26 3.2 Main Nine Ending Share Increase . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26 3.3 Nine Ending Share Increase vs. Fraction of Nines . . . . . . . . . . . 27 3.4 Nine Ending Share Increase vs. Lagged Fraction of Nines . . . . . . 28 3.5 Nine Ending Share Increase vs. Fraction of Nines and Lagged Fraction of N ines . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28 3.6 Probability of Purchase some item vs. High and Low Budget . . . . 29 3.7 Nine Ending Share Increase vs. Budget Size . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30 3.8 Nine Ending Share Increase vs. Budget Size and Fraction of Nines 30 3.9 Nine Ending Share Increase vs. Sequence of Choices . . . . . . . . . 3.10 Nine Ending Share Increase vs. Budget Size and Sequence of Choices 31 32 . . . . . . . . . . . . 37 . . . . . . . . . . . 48 C.2 The Most Popular Products at LaVerdes - Part II . . . . . . . . . . . 49 C.3 The Most Popular Products at LaVerdes - Part III . . . . . . . . . . 50 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51 A.1 A Survey on Online Grocery Stores - Oct 1999 C.1 The Most Popular Products at LaVerdes - Part I C.4 30 Categories by Fraction-of-Nines 7 Chapter 1 Introduction One rapidly developing area on the Internet is on-line grocery shopping. Such services, which usually include home delivery, may be either local or national. In the Boston area, on-line grocers such as HomeRuns (http://www.homeruns.com), PeaPod (http://www.peapod.com), Streamline (http://www.streamline.com) and ShopLink (http://www.shoplink.com) are facing tough competition in the electronic market. One characteristic of Internet grocery stores is that they provide a shopping environment in which prices frequently end in the digit 9, as is also the case in many physical grocery stores. Many on-line grocery stores in fact use prices that only end in 9. However, the effects of this policy are poorly understood. This thesis reports an experiment that seeks to determine whether prices ending in nine influence consumer shopping behavior in on-line grocery stores. Chapter one gives the motivation for the study and a background review of price endings, focusing on consumer behavior. Chapter two presents the experimental design and hypotheses along with the methods used for data cleaning and analysis. Chapter three gives the results and discusses their significance. Chapter four makes several observations about on-line experiments and summarizes the study's conclusions. 8 1.1 Motivation for Studying Nine-Endings Nine-Ending Effect The study of prices that end in nine (nine-endings) has gained increasing attention due to the high saturation of 9s in the market. A number of previous studies and experiments have already found that nine-endings have a significant positive effect on product choice. However, most of these studies have examined the effect only on scanner-panel data for grocery goods, or on sales data from non-grocery catalogs. Only one study, Ouyang [4], has examined the effect on on-line grocery shopping via a web-based experiment. Even in this experiment, the results require further testing. As mentioned earlier, not only do many physical grocery stores use almost all nineendings, but many on-line grocery stores do the same. Such high usage of nine-endings may not be an optimal strategy in the online market, especially since products are presented differently online than in the physical store. In addition, pricing strategy currently varies across online grocery stores. (see Table A.1) As more and more commerce is transacted via the Internet, it becomes increasingly important to learn how nine-endings affect electronic shopping. Such understanding would help retailers decide on pricing strategies for these environment. Fraction of Nines Effect Past studies have suggested that a high fraction of nine- ending products decreases the positive effects of nine-endings. (Ouyang [4]; Ouyang, Zeithammer and Little [5]) Similarly, in scanner-panel data, the higher the fraction of nines, the lower the nine-ending effect appears to be. A similar relationship has been found in an experiment studying sales of fashion goods in mail catalogs. (Anderson and Simester [1]) As for on-line grocery products, this effect has yet to be measured thoroughly. 9 1.2 1.2.1 Literature Review Underestimation of Actual Price Frequently, products with a nine-ending have been observed to produce a higher demand than those without it. One popular belief is that nine-endings increase product appeal, which in turn, increases the likelihood that an individual will buy. This effect has several possible explanations, one of which is the so called underestimation mechanism. The underlying theory is that consumers underestimate the actual price of the product when it ends in nine. By ignoring the right-hand digit 9 of the price, they truncate or round down the actual price. Some evidence has been observed in a study conducted by Schindler and Kibarian [7]. They find that a 99-price ending leads to an increase in total consumer sales as compared to the next higher 00-price ending. Unfortunately, that particular experiment fell short of finding statistically significant support for the mechanisms involved. The underestimation mechanism was further studied by Stiving and Unnava [8]. They consider many different price-pairs, including ones that involve nine-endings and showed that consumers underestimate prices in certain situations. In making choices between products, consumers may use a rounding down heuristic that ignores the right hand digits when the difference between two numbers is hard to calculate mentally. If the prices involve numbers that are easy to subtract, consumers are likely to subtract them. Otherwise, consumers often estimate the price difference by ignoring the right hand digits. For example, if the two prices are $3.74 and $3.69, then subtraction of 74-69 is difficult. Therefore, some people will tend to round down and hastily conclude that the difference between these two prices is 10 instead of 5. Their experiments indicate that the underestimation mechanism not only works in the abstract, but also generates potential market effects when applied to a product choice task. As hypothesized, consumers who are less comfortable manipulating numbers are more likely to use a rounding down heuristic to evaluate prices. This study not only verifies that some consumers underestimate certain prices, but also offers support for just-below pricing, a common practice used by retailers. 10 Underestimation is a well understood mechanism but not the only possible explanation for the nine-ending effect on product demand. Other explanations have been developed, particularly the "meaning" effect described below. 1.2.2 Association of Meanings to Prices A discussion of the meaning effect begins with the observation that consumers are usually not able to remember the exact prices of items they have recently purchased. Rather than paying close attention to prices, consumers acquire just enough information to make their purchase decisions. They do not consciously remember exact prices, as would be expected. For example, a study conducted by Monroe and Lee [3] shows that consumers do not fully process price information but maintain internal reference prices to evaluate products. Furthermore, Schindler [6] proposes that consumers apply their own intuitive meanings to price endings. People establish special meanings for price endings through subconscious learning of correlations that occur in the marketplace. These correlations then serve as a catalyst that connects meanings to price endings during purchase. In particular, Schindler mentions 14 possible meanings, listed below, that can be associated with the last digit of a price. For instance, the digit nine has been found to connote discount or sale prices. In general, empirical evidence has been found to support the effects of some of these meanings and possible underlying mechanisms have been discussed in literature, but most of them have not been thoroughly examined in controlled studies. Price Meanings that may be Stimulated by Price Endings 1. The price is low 2. Price has been reduced 3. Price has not been increased recently 4. Discount or sale price 5. Price results from a careful and precise process 6. Price is negotiable 7. Price is synonymous with even-dollar amount 11 8. Price is the correct price Meanings Concerning Non-Price Attributes of the Product or Retailer 1. Low quality merchandise 2. Retailer is sneaky, slick, or doesn't play it straight 3. High quality merchandise 4. Classiness, sophistication, or prestige 5. Distinctive signature of retailer 6. Playfulness 1.3 Current Nine-Ending Theories The association between meanings and prices is used in several current theories to explain the impact of nine-endings on consumer behaviors. The theories may apply differently to different people or circumstances. In particular, Zeithammer [10] focuses on possible mechanisms that would facilitate the association of low prices and nineendings in the minds of consumers. These are described below. Some of them may help explain the results of the experiment in this study. Not Aware of Existing Meaning One theory suggests that consumers have been conditioned by the high proportion of nine-endings in the current market. People need to buy products and gain value from doing so. Therefore, they subconsciously attach a meaning to nine-endings whenever they buy an item with a nine-ending. The conditioning intensifies as the number of items with nine-endings increases. Fully Aware of Existing Meaning A further hypothesis proposes not only that consumers associate nine-endings with meanings but also that retailers recognize the situation. Nine-endings serves two purposes in this case. They are a purchasing decision indicator for the consumers and also a price setting regulator for retailers. Consumers recognize that a certain amount of nine-endings in the market implies low prices. Based on this recognition, consumers then decide whether or not to buy. In 12 response, the retailers deliberately set the proportion of nine-endings at a level they have recognized to favor a sale. Thus, nine-endings can generate either a positive or a negative effect on sales, depending on the proportion of nine-endings and the amount of information they provide. Meaning Does Not Exist Two further theories examine mechanisms that could cause consumers to believe in nine-ending meanings that do not actually exist. The consumers' limited ability to process information is one possible cause. Consumers may erroneously attach meanings to nine-endings by inaccurately inferring an empirical relationship between prices and some property of interest, for example, nineendings and low price, even though the correlation is not actually there. With the high proportion of nine-ending prices in the market, it would not be surprising for consumers to find evidence to support a particular belief. The other theory suggests that consumers do not need all the information contained in the number used to denote price. They may only need a rough idea about relative cost to make subsequent decision. Therefore, consumers may underestimate prices (truncate the penny digit) or categorize products simply as relatively "cheap" or "expensive". Considering the high proportion of nine-endings in the market and the inclination to reduce mental processing (see section 1.2.1), consumers have incentives to truncate prices and unavoidably notice the nine-endings. Truncating a nine-ending leads to a price much less than the original. Thus, the consequence of this behavior is a perceived association of low prices and nine-endings. (see Zeithammer [10] for further discussion of this theory) 1.4 Modeling the Effect of Nine-Ending in Consumer Choice A common technique for testing nine-ending theories is to build a model of product choice based on an implicit utility function for the consumer. This technique can be used to predict how consumers behave toward price endings. For example, a logit 13 model by Little and Ginise [2] uncovers significant effects of prices ending in nine. Using scanner data on pancake syrup, their study discovers that a price ending in nine increases the probability of purchase. In addition to the basic logit model, Stiving and Winer [9] incorporate behavioral theories in the utility function. They design models that consider for both the underestimation effect and the meaning effect, called the "level" and "image" effect respectively in their study. They find significant image effect in the digits 0 and 9. The digit 0 suggests a higher quality and the digit 9 signals both lower quality and good price. Their work underscores the importance of accounting for individual price digits in consumer choice models. 14 Chapter 2 Experimental Design 2.1 Objective The objective of the online simulation is 1) to develop a web-based method for measuring the nine-ending effect and 2) to measure the moderating influence of several shopping conditions on the magnitude of the effect. 2.2 Nine-ending Effect Measuring Methodology The basic task of a subject in the experiment is to select a market basket of goods consisting of at most one product from each of 30 categories. Each category contains five products to choose from plus the option of not choosing anything. The experiment employs a method that uses simple calculations such as counting and taking differences to measure the average nine-ending effect across subjects. One product in each category is designated as "product A" for that category. Only the price ending of Product A changes during the experiment. The rest of the products' prices are kept constant and used only to create different shopping environments. In particular, Product A is assigned either a 9-ending or an 8-ending. The nineending effect is then measured as the difference of product A's share between the two price-ending conditions. This procedure enhances the validity of the measurement by keeping everything else (prices and products) constant and varying only the price 15 ending digit of product A between 9 and 8. 2.3 Nine-Ending Phenomena to be Studied In order to understand the strength of the nine-ending effect more thoroughly, the study is also designed to examine the influence of the following moderating variables: Fraction of Nines in the Current Choice Set The fraction of nines in the choice set is hypothesized to affect the magnitude of the nine-ending effect. Notice that the actual fraction of nines seen by a subject depends slightly on whether product A has a 9 or 8 ending. To resolve this ambiguity, fraction of nines is arbitrarily defined to be exclusive of Product A. Therefore, the fraction of nines for a specific category is simply the fraction of the 4 non-A products with a nine-ending. As mentioned in Chapter 1, fraction of nines have been observed to weaken the strength of the nineending effect with increasing fraction of nines. The measurement of this relationship in the past online grocery shopping experiment has not been statistically significant. (Ouyang, Zeithammer and Little [5]) The current study hopes to give a more accurate picture of this inverse relationship. It is hypothesized that a decreasing fraction of nines may strengthen the nine-ending effect. Lagged Fraction of Nines Similarly, the fraction of nines of the category en- countered in the period before the present category may also influence the subject's purchase decision. Notice that, if shoppers skip a category, they do not see its fraction of nines. Therefore, the relevant lagged fraction of nines corresponds to the category in which shoppers last made a choice. According to this definition, the strength of the present nine-ending effect may rise or fall depending on whether the lagged fraction of nines is higher or lower. Most likely, the relationship should resemble the one for nine-endings in the current choice set. If the shoppers have last seen a high fraction category, it is hypothesized that they are less likely to buy products with a nine ending. 16 Interactions of Fraction of Nines and Lagged Fraction of Nines Both of these moderating variables, fraction of nines and lagged fraction of nines, may jointly influence the nine-ending effect. For example, the combination of having a high present fraction of nines and a low lagged fraction of nines may weaken the nineending effect. This hypothesis is based on the same rationale as for the fraction of nine effect. It suggests that the strength of the nine-ending effect decreases as the subject's exposure to nines increases. In this case, any effect already associated with a high or low fraction of nines would be intensified. If the present fraction of nines is high, then it would seem even higher if the prior fraction of nines is low. Similarly, a high lagged fraction of nines would emphasize the effect of low fraction. Thus, the nine-ending effect may depend on the polarity between the present and the last fraction of nines. If shoppers have last seen a high fraction and the current choice set has a low fraction, then customers are expected to be more likely to make a purchase of a product that ends in nine. Order in Sequence of Choices Another moderating variable that may yield in- teresting insight is the order in which purchases are made during the experiment. The nine-ending effect is expected to become stronger in the categories that are encountered later in the experiment. Subjects may become tired as they progress. The more fatigued they are, the less attention they will pay to prices. As a result, shoppers may be more prone to the nine-ending effects. Therefore, the first 15 categories encountered are expected have a weaker nine-ending effect than the last 15 categories. Order of Product A in the Choice Set In the experiment, each aisle displays its 5 products in a list. This is how most on-line groceries present their products. However, the attention that each product receives may vary depending on its position in the list. People generally look at items from top to bottom. More attention may be given to the items near the top. Consequently, the nine-ending effect is hypothesized to be stronger for the products listed near the bottom than the top. 17 Size of the Individual's Budget The experiment subjects are assigned to either a large ($80) or a small ($40) budget and are asked to stay within it. Increasing the budget is expected to decrease the importance of price. As a result, prices matter less, making the nine-ending effect more likely. In addition, the budget constraint is expected to affect purchasing behavior. The people with a high budget will have different shopping objective and strategy than people with a low budget. This difference may either increase or reduce the nineending effect depending on the situation. For example, the low budget group may stop buying towards the end of the experiment, while the high budget group may buy more seeing that they have plenty of money left. In general, the subjects with a high budget are expected to purchase a larger total amount of products than the subjects with a low budget even though the shopping task they have been given is the same. Thus, the high budget constraint may induce a stronger fraction-of-nine effect than the low budget constraint. 2.4 Overall Description In a simulated on-line grocery store, respondents are asked to choose a list of goods from 30 selected categories. A budget constraint of $80 or $40 is assigned randomly to individual shoppers. The 30 categories are described as 30 different "aisles". The experiment assigns the aisles in a random order to each shopper. In each aisle, shoppers are first asked to pick a "style" that they prefer for the products associated with that aisle. A style is usually a prominent characteristic associated with products of a particular aisle, for example, flavor is a style of ice cream. Shoppers do not have to pick a style, they can choose to skip an aisle completely and proceed to the next. If they do pick a style, then they will see a list of 5 products, identified by brand name and price. The shopper can choose to buy any of the 5 products or not purchase any of them. After the shoppers have gone through the 30 aisles, they are asked to fill out a 18 two-page questionnaire. The first page inquires about their brand preferences. The second page asks about the subject's past on-line shopping experiences. On the first page is a list of the 30 categories with the corresponding 5 product brand names but no prices. Participants are asked to buy one product from each category as if price were not a concern. Again, the participant can choose not to buy anything. The order of the 30 categories and the 5 products in each category are both randomly generated for every participant. The experiment was conducted online for one week and also during a two-hour walk-in session at a computer cluster. I recruited respondents by posters throughout the MIT campus (including residential halls and computer clusters) and by sending email messages to several mailing lists. The participants were compensated with a free movie ticket. An additional ticket was given to participants who took the experiment during the walk-in session. Please see Appendix B for the screens of the online experiment. 2.5 Generation of Categories and Products Considerable care is required in constructing categories and products for the experiment. The guidelines were as follow: 1. Select 30 categories and a set of 5 substitutable products in each category. Each category must: (a) Contain 5 different brands, without including any house-brands. (b) Not be dominated by a single brand (e.g. Coke dominates the soft drink category). (c) Be popular among the MIT community. A popular category is defined as one that receives high volume sales at LaVerdes, the only grocery store on the MIT campus (see Appendix C for the list of high volume sales). All individual products within a category must be: 19 (a) Popular among MIT population, defined as having high volume sales at LaVerdes. (b) Not house brands. (c) Substitutes for other products in the same category (e.g. products having the same size). 2. Keep the prices of the products similar to those found in the local supermarkets and online grocery stores popular to the MIT community. To do this: (a) Obtain the real product prices and unit prices from Star Market, LaVerdes and HomeRuns. (b) Using the unit prices as a measure of relative price between products, adjust the original product prices according to the heuristic discussed in the Price Adjustment section below. 3. For each category, randomly pick one of the five products to be designated as Product A. Product A of each category will have one of two possible price endings, either 9 or 8. The prices of the other products stay constant. For each subject and each Product A, the 8 or 9 is assigned at random with equal probability. Notice that the position of product A in the list is critical since it may vary the strength of nine-ending effect. Thus, it is important to make sure that there is an equal number of Product As (6 in this case) occupying the same position on the list of 5 products. (6 * 5 possible positions = 30 categories) 4. First randomly assign 6 categories to each of the five levels of fraction of nines. Then check that the assignment satisfies the following criteria: Note that there are 5 levels of fraction of nines (0.0 0.25 0.50 0.75 1.0) as defined in the previous chapter. Since there is a total of 30 categories; therefore, each level of fraction of nines should be found in 6 different categories. 20 (a) The following categories are distributed evenly among the different levels of fraction of nines. These particular categories represent products that are similar in that the 5 products within the category differ by only one or two features (other than brand names). " " " " " " " " * " " paper towel shampoo toothpaste water dish-washing soap pasta detergent trash bags cups plates pasta (b) Categories that are price sensitive are distributed across the different levels of fraction of nines. According to data from Ouyang [4], the following four categories are significantly sensitive to price variations: 1) Frozen Dinner, 2) Juices, 3) Cereal, 4) Ice cream. (Ouyang's experiment data for ice cream was distorted by subject's misinterpretation, but ice cream is still assumed to be price sensitive because it is a non-esessential item.) (c) Ordering of Product As: In a list of five products, the product A can be placed in one of 5 possible positions (1st(top), 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th(bottom)). The different positions of product A from a specific level of fraction of nines should span the 5 possibilities. (d) To avoid biases related to the characteristics of Product A, at least one of the product As from each fraction of nines levels should be the following: i. The most popular in the category according to LaVerdes' sales information and the local Star Market sales observations. ii. The most expensive of the 5 products in the category. iii. The cheapest in the category. 21 iv. An average item that lacks the first three features. Please see Table C.4 for a list of the 30 aisles used in the experiment and their corresponding levels of fraction of nines. 2.6 Pricing Adjustment In adjusting the prices, we use a heuristic that minimizes the influence of underestimation, as defined by Stiving and Unnava [8]. According to the study, people tend to round down prices when they compare price pairs that are difficult. Since people process price information from left to right, they are more likely to round down when the difference between two prices is difficult to calculate. Individuals who are less inclined to perform numerical computation round down more frequently. Therefore, prices in this experiment are adjusted to minimize these situations, eliminating the possibility of having the underestimation effect as an important explanatory variable. 2.7 Data Collection and Cleaning Over 500 subjects were recruited during a one week period in which the experiment operated. An additional 25 people participated during a two-hour walk-in session conducted at a computer cluster. The walk-in sample formed a control group to develop norms for screening outliers. Individuals were eliminated for whom " Average time spent per aisle visited was too long (greater than 25 seconds) or too short (less than 5 seconds). " Total number of aisles visited was too few (less than 15). These two parameters measure the engagement level of our subjects. Time spent per aisle measures the time subjects take to make a choice in a particular aisle. A choice could be the act of either buying one of the 5 products or making no purchase. The time spent in choosing the style of products is excluded, since the subjects have 22 not seen the product list at that point. The total number of aisles visited includes only the aisles in which a subject bought a product or chose not to buy anything after examining the 5 products. See Figures D-1 and D-2 for histograms of the walk-in and on-line subjects used for data analysis. Statistical Analysis 2.8 Statistical Properties of the Measured Difference in 2.8.1 Shares The notations and equations used in the discussion of the various nine-ending effects are as follows: " N denotes the number of participants " K denotes the number of categories of products " M denotes the number of distinct levels that change the strength of nine-ending effect (e.g. Each category can appear early or late during the experiment, thus M = 2 in this case.) * Slk,m denotes the share of Product A with a nine-ending in category k and level m * SOk,m denotes the share of Product A without a nine-ending in category k with m levels * Slk,m-SOk,m yields the estimate of the nine-ending effect for category k and level m. " Sk,m is defined as Slk,m-SOk,m Since the nine and non-nine ending of Product A is randomized, approximately N/M participants will input an observation in each condition. To estimate variance, each choice of Product A is modeled as a Bernoulli process with an underlying probabilities POk,m and Plk,m respectively. Bernoulli choice implies E[Slk,m - SOk,m1=Plk,m - POk,m 23 Var[Slk,m - SOk,m]=(2M/N)[Plk,m(1 - Plk,m) + POk,m(1 - POk,m)] Estimates are aggregated across categories to gain precision. Using the assumption that each m-specific nine-ending effect is a fixed incremental gain in probability of choosing Product A, the estimate of the average difference across categories is the precision-weighted average of the differences in share A Sk,m, where precision is the inverse of the variance: A Sm = (Totar1Pecision) Zk11 precision(A Sk,m) ASk,m where precision(ASk,m) Var[zXSk,m] (2M/N) = N2M Plk,m(1-Plk,m)+POk,m(1-PI,m) N12M zKi-k1Plk,m,(l-Plk,m)+POk,m(1-POk,M) 24 - Chapter 3 Result Discussion 3.0.2 Hypothesis Testing The effects proposed in the previous chapter are considered using a null hypothesis that the phenomena discussed have no effect. Values for averages and standard errors are computed using the equations defined in the previous chapter. This chapter presents the results and discusses the findings. 3.0.3 Main Nine-Ending Effect The basic measure of the nine-ending effect is the difference in Product A's share with a nine ending and Product A's share with an eight ending. As shown on Table 3.1, a little more than half of the categories have positive effects and only four have a significant positive effect (taken to be a t >= 1.6). With so many categories showing negative values, the average nine-ending effect is rather small and analysis shows it not to be statistically significant. See Table 3.2. A possible reason for this is the noise inherent to the design of the experiment. The budget constraint may have caused the low budget people to shop quite differently from the high budget group. Since the low budget group contributes roughly half of the sample, their behavior may introduce noise that obscures a positive effect in the high budget group. Thus, the nine-ending effect may be important in online shopping, but experimental noise has made it hard to detect in aggregate analysis. 25 Table 3.1: Main Nine Ending Effect Ranking Category Name Increase in Standard Error t-value 0.063 0.069 0.039 0.031 0.060 0.033 0.054 0.068 0.057 0.038 0.058 0.045 0.027 0.023 0.059 0.018 0.028 0.049 0.055 0.062 0.063 0.058 0.054 0.020 0.035 0.055 0.063 0.050 0.066 0.065 2.031 1.347 2.076 2.290 0.983 1.666 0.907 0.617 0.666 0.973 0.620 0.733 1.148 1.217 0.389 0.333 -0.142 -0.102 -0.127 -0.209 -0.222 -0.344 -0.629 -1.75 -1.114 -0.818 -1.015 -1.48 -1.439 -1.830 Product A Share 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Disposable Plates Pasta in a Bag Ice Cream-1 Pint Paper Towels Pasta Sauce Water Bread Chocolate Chip Cookies Pasta in a Box Toothpaste Breakfast Cereal Yogurt Jam or Jellies Corn flakes Orange Juice Laundry Detergent Tea Bag Canned Vegetables Cranberry Juice Shampoo Frozen Entree Dish Washing Liquid Trash Bags Mayonnaise Soup Disposable Cups Potato Chips Milk Coffee Ice Cream-1/2 Gallon 0.128 0.093 0.081 0.071 0.059 0.055 0.049 0.042 0.038 0.037 0.036 0.033 0.031 0.028 0.023 0.006 -0.004 -0.005 -0.007 -0.013 -0.014 -0.020 -0.034 -0.035 -0.039 -0.045 -0.064 -0.074 -0.095 -0.119 Table 3.2: Main Nine Ending Share Increase Nine-Ending across 30 categories Increase in Product A Share 0.009 26 Standard Error t-value 0.007 1.285 Table 3.3: Nine Ending Share Increase vs. Fraction of Nines Frac9 Level 0 0.25 0.5 0.75 1 3.0.4 Increase in Product A Share 0.023 -0.008 -0.004 0.021 0.040 Standard Error t-value 0.024 0.012 0.017 0.014 0.019 0.958 -0.666 -0.235 1.5 2.105 Fraction of Nines Contrary to expectations, the result for the fraction of nines effect, as shown on Table 3.3, does not show a diminishing effect for increasing fraction of nines. If anything, the results suggest the opposite. High fraction of nines seems to produce a higher nine-ending effect. The absence of the expected relationship again suggest that the low budget constraint may be adding noise. Also, the type of categories representing the different fractions may introduce more variance than originally expected. Nine Ending Share Increase vs. Lagged Fraction of Nines Effect Lagged fraction of nines, i.e. nines encountered in the prior period, was expected to affect the strength of nine-endings in the current period. However, no statistically significant relationship is apparent between nine-endings and the lagged fraction of nines, as can be seen in Table 3.4. This may have been affected by the experimental design. In each aisle, shoppers go through a style page before seeing the list of products, the actual fraction of nines. Consequently, the effect of the nines encountered in the previous aisle may be attenuated. Interactions of Fraction of Nines and Lagged Fraction of Nines Not sur- prisingly, given the results just discussed, the interaction between fraction of nines and lagged fraction of nines is found to be insignificant as well. The high and low fractions shown in Table 3.5 are defined as follows. 1) fraction of nines of zero or a quarter are considered to be low, 2) high fraction of nines refer to the fraction of 27 Table 3.4: Nine Ending Share Increase vs. Lagged Fraction of Nines Lagged Frac9 Level Increase in Standard Error t-value 0.023 0.012 0.022 0.025 0.023 0.130 -0.666 1.045 -0.480 1.347 Product A Share 0 0.25 0.5 0.75 1 0.003 -0.008 0.023 -0.012 0.031 Table 3.5: Nine Ending Share Increase vs. Fraction of Nines and Lagged Fraction of Nines Fraction of Nines- Increase in Lagged Frac9 Product A Share High-Low High-High Low-Low Low-High 0.035 0.04 0.006 0.032 Standard Error t-value 0.026 0.028 0.026 0.026 1.346 1.428 0.230 1.230 three quarters or one and 3) fraction of nines of a half is considered as neither high nor low. 3.0.5 Ordering of Product A within a Choice Set The effect of nine-endings was hypothesized to increase as the item appears lower on the list of choices. However, the experimental results yield no clear pattern that would support this prediction. A likely reason is that our list is short. The original prediction assumes that shoppers become tired from looking at a list, and as a result, gives less attention to the items on the bottom of the list. This does not seem to apply to our list of only 5 products. In such a short list, all products in each choice set may receive an equivalent amount of attention. 28 Table 3.6: Probability of Purchase some item vs. High and Low Budget Budget Size High Budget Low Budget 3.0.6 Probability of Purchase 0.851 0.565 Standard Error 0.006 0.009 Probability of Purchasing of the Two Budget Groups Before moving into the analysis related to budget sizes, Table 3.6 provides the likelihood of purchasing some item (any item), regardless of its price ending, for the two budget groups. The people given an $80 budget are much more likely to make a purchase than the people with a $40 budget, almost 30 percent more. Such differences are to be expected. People with different amount of spending money are expected to use different shopping strategies. Moreover, this probability difference can be interpreted as an indicator that the experiment participants are behaving as if they were shopping for real. They shop according to the budget assigned and try to stay within their spending limits. 3.0.7 Budget Size Since the budget size is suspected of introducing variance, both the nine-ending and fraction of nines are evaluated by budget size as shown in Table 3.7 and Table 3.8. The high budget group shows a positive nine-ending effect of 2.6%, which is significantly greater than zero. The low budget group shows a non-significant negative effect. The two effects together, one positive and the other a near zero, indicate that the budget constraint was an effective control variable, strong enough to turn the nine-ending effect on and off. These results also support the contention that the reason the main effect is not significant is that the low budget group has no effect and is simply adding noise that dilutes the significant effect of the high group. It turns out that the fraction of nines effect does not yield the expected pattern even in the high budget group. See Table 3.8. However, the consistency of having 29 Table 3.7: Nine Ending Share Increase vs. Budget Size Budget Size Increase in Standard Error t-value 0.01 0.01 -0.600 2.600 Product A Share Low High -0.006 0.026 Table 3.8: Nine Ending Share Increase vs. Budget Size and Fraction of Nines Budget SizeFraction of Nines High-Frac9=0 High-Frac9=0.25 High-Frac9=0.5 High-Frac9=0.75 High-Frac9=1 Low-Frac9=0 Low-Frac9=0.25 Low-Frac9=0.5 Low-Frac9=0.75 Low-Frac9=1 Increase in Product A Share 0.017 0.023 0.007 0.023 0.075 0.041 -0.017 -0.032 0.009 -0.008 Standard Error t-value 0.031 0.022 0.021 0.020 0.027 0.038 0.017 0.026 0.018 0.028 0.548 1.045 0.333 1.150 2.777 1.078 -1.000 -1.230 0.500 -0.285 positive effect in all the high budget's fractions confirms that the high budget people indeed are shopping differently than the low budget group. More importantly, this result supports the initial prediction that people with more spending money are less concerned with prices and therefore, more easily influenced by the nine-ending effect. The high budget people were given more than enough money to buy every most expensive product in all 30 aisles. With hardly any pressure from the budget constraint, they not only buy more products but also become more susceptible to the nine-ending effect. Looking from the retailers point of view, the result indicates that people pay less attention to prices and become more likely to buy products with a nine price-ending when money is less of a concern. On the other hand, there appears to be less advantages for using a nine-ending when the economy is bad. As seen in the low budget group, people are less attracted to prices ending in nine when prices become important. 30 Table 3.9: Nine Ending Share Increase vs. Sequence of Choices 3.0.8 Sequence Increase in of Choices Product A Share Early Late 0.002 0.017 Standard Error t-value 0.010 0.010 0.200 1.700 Sequence of Choices during the Experiment One interesting result has emerged from an examination of the sequence of choices during the experiment. The entire sample of choices is divided into two sets: choices that are made in the first half of the shopping trip and choices that are made in the second half of the trip. These two sets are denoted as "early" and "late" respectively. The two sets display different results. The late set shows a strong nine-ending effect of 1.7 share points, which is much higher than the approximately zero effect in the early set. As can be seen in Table 3.9, this result suggests that shoppers are more susceptible to nine-ending effect during the latter part of the shopping trip. The reason may be shopping fatigue, the longer people shop, the less attention they pay to prices and the more susceptible they become to the nine-ending effect. Furthermore, it may be possible that time becomes a concern for people towards the end of the experiment. This may suggest that shoppers with limited amount of shopping time are more likely to buy products with a nine ending. As most of the Internet shoppers are pressed for time, this may suggest that Internet grocery stores should set many price endings to nine, especially at the "express" shopping section if available. In general, retailers may benefit from implementing this policy if they know that the majority of their customers are purchasing in a hurry. In terms of the underlying mechanism, the nine-ending effect may be caused by the meaning effect as described in Chapter 1. The more tired the shoppers become, the less they fully process price information and the more they rely on price meanings in making a purchase decision. 31 Table 3.10: Nine Ending Share Increase vs. Budget Size and Sequence of Choices Budget SizeSequence of Choices Low-Early Low-Late High-Early High-Late 3.0.9 Increase in Product A Share -0.006 -0.002 0.024 0.029 Standard Error t-value 0.014 0.016 0.014 0.013 -0.428 -0.125 1.714 2.230 Budget Size and Sequence of Choices In light of the previous finding, the sample is now separated into the following four subgroups to examine the combinational effect of budget size and order in sequence of choices: 1) choices that are made early in the shopping trip by a high budget person, 2) choices that are made late in the trip by a high budget person, 3) choices made early in the trip by a low budget person and 4) choices that are made late in the experiment by a low budget person. The results are tabulated in Figure 3.10 The sequence of choice effect appears in both high budget and low budget groups, although the reduction in sample size required in sorting observations into more cells leaves the results short of statistical significant. 32 Chapter 4 Comments and Summary 4.1 Doing the Online Experiment in the Lab vs. Elsewhere The web is a good medium for collecting a large set of diverse data in a short period of time. However, it also allows room for many sources of distractions. Capturing the full attention of the subjects becomes more challenging since many other activities can be done at the same time as the experiment, for example, playing computer games. Thus, an interesting aspect of the experiment is to try to compare the engagement level of our subjects, in lab versus anywhere else. The walk-in session provided a traditional lab environment that is considered to provide the control needed for running an experiment. The experimenter found that the walk-ins were more engaged in their tasks than the subjects who performed the experiment in unsupervised locations. The walk-in session also proved to be useful for getting direct feedback about specific concerns of the subjects. Some of these issues had been uncovered in pilot testing, but the larger walk-in sample provided further insights. As has been seen in the previous chapter, the walk-in samples provided parameters for reliably cleaning the rest of the samples. For future web-based experiments, it would be beneficial to conduct a controlled session in parallel, in addition to the pilot testing done in advance. 33 4.2 Using Hypothetical Products The use of hypothetical products did not generate distraction for the subjects. The subjects were warned in advance that some hypothetical products would be used and were comfortable shopping with them. Ideally, hypothetical products would not have been used, but they were required to implement the design structure. Comments from the walk-ins and other subjects actually reported that they found the grocery store realistic. 4.3 Future Research The experiment was designed so that a first level of analysis could be performed by simple counts and averages, and those are the results reported here. However, the data collected will be further explored using various models. One example would be a logit model where the loyalty preference from the subjects will be considered in the measurement of the nine-ending effect. Further investigation of other possible moderating variables on the nine-ending effect may yield further insights into shopping behavior of the high and low budget groups. Possible moderating variables are the relative price and popularity of product A as compared to the other products in the same category. Future measurements of the nine-ending effect should consider and try to eliminate any biases detected in the design of this experiment. As for future testing, one particular area of interest would be to examine how the choice of online stores is related to the number of nine-ending products carried by the store. Another area would involve further investigation of the various possible meanings associated with nine endings under different circumstances. 4.4 Conclusion Two clear pictures emerge from the discussion in the previous chapters. The nineending effect is most influential when it is seen towards the end of a shopping trip. Perhaps all the products near the check out counter should be priced with a nine 34 ending! The second picture suggests that nine endings will be most effective whenever the economy is good. People with more spending money are more likely to buy products with a nine price ending. This also suggests that gourmet food stores, tailoring to expensive shoppers, might gain an advantage from pricing many of their products with a nine ending. 35 Appendix A Online Survey 36 Table A.1: A Survey on Online Grocery Stores - Oct 1999 OnLine Grocers Price Ending Unit Price Product Description Homeruns Mostly 9 Yes Text optional Detailed Price Info Yes Size Info Yes On Sale Icon Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No No Yes Yes No No Yes Yes No No No Yes No No No Yes No No No Yes No No No No Yes Yes No No Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes No No No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Personal List images Peapod 9 only Yes Text optional images Yourgrocer 9 only No Netgrocer Mostly 9 Yes Grocexp Mostly 9 No Harryanddavid All in 5 No Northwestgrocer Mostly 9 No Latingrocer All Digits No Text and images Text only, extra images for featured items Text and Peachtreenetwork Webvan Mostly 9 Many 7 No No Text Text and Gourmet-grocer Groceronline Mostly 0 or 5 All Digits Streamline Mostly 9 Text, optional images Text and images Text and images images images No Yes Text Text and images No Text, optional images 37 Appendix B Web Experiment 38 Figure B-1: Login Page The ART of Shopping Mini Mart is an online shopping research project at MIT. Our goal is to understand how shopping in the future will be done and to find ways to improve the experience for both the customer and the seller. In particular, we wish to understand the customers' tradeoff among price and quality characteristics in an online setting so that customers' needs can best be met by the seller's offerings. In the current experiment, we invite participation from the MIT community only. It involves choosing groceries from available products in several categories and answering three questions at the end of the study. No groceries are actually purchased. Participation is entirely voluntary. The time required is about 15 minutes. You can stop at any time by clicking the QUIT button. Responses will be anonymous. You will be recognized with a random number only. You may skip any question, although if you skip very many, your response may be unusable. For your participation in the simulated shopping trip, you will be offered a reward of SONY movie ticket. Even though early withdrawal from the study is discouraged, you will be compensated with a movie ticket regardless. If you have any questions or problems, please contact Minnie Lau (scarb@mit.edu, 617-441-3569) or Professor John D. C. Little (jlittle@mit.edu, ext. 3-3738). I understandthat I may contact the Chairmanof the Committee on the Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects, MIT 253-6787, if Ifeel I have been treatedunfairly as a subject. * I've read the above and would like to participate * No, I do not wish to participate at this time 39 Figure B-2: Scenario Scenario It's only the middle of the week and your fridge is already running out of food. You've also realized how busy your schedule will be, so you decide to order your next week's groceries from your favorite online grocer, Mini Mart. Mini Mart is an on-line grocery store that offers all the products you want with FREE delivery. However, it is currently undergoing restructuring to test a new "electronic-aisle" concept, designed to ease your shopping experience. The new structure will guide you through the store and present the store "aisles" one by one. There are a total of 30 aisles, each containing one category of product. Please select one item per aisle. If you never purchase in that aisle, you may skip it altogether by selecting this tag: . If you do not wish to purchase any of the items offered, indicate "no purchase". Also note that a few products are hypothetical for the purpose of this experiment and may not exist in the real world. Please stay within your budget limit! 95% of the experiment consist of the shopping simulation above and the remaining 5% involve a short survey. PLEASE: * DO NOT participate more than once in the experiment, but feel free to ask others to participate. * Make your choices carefully, your input is valuable to our research. * Have fun. Thank you very much for your time and participation. Enter Here! 40 Figure B-3: Bread Style - First part of a sample aisle 'Maft What kind of bread do you prefer? 0 Oat & Oatmeal 0 Pumpernickel 0 Raisin & Cinnamon Rye 0 SourDough 0 White 0 12, 9 or 7 Grain Please make your choices carefully!O Whole Wheat Your input is important to our research. 05b ths categbry 41 Figure B-4: Bread Choices - Second part of a sample aisle Your Current Cart Total : $8.21 You have 22 aisles left to visit. Please plan ahead to stay within your BUDGET: $ 80 Rye Bread - 16oz packaged Price Choice Brand $1.79 0 Bouyea Fassetts $1.99 0 Country Kitchen $1.89 0 J.J.Nissen $1.49 Wonder $1.58 0 0 Arnold's 0 no purchase Next] 42 Please make your choices carefully. You input is important to our research. Figure B-5: Tooth Paste Style - First part of a sample aisle )Mart Please pick your favorite kind of toothpaste: o Regular 0With Baking Soda Please make your choicesOWith Tartar Control carefully! Your input is important to our 0 Extra Whitening research. 43 Figure B-6: Tooth Paste Choices - Second part of a sample aisle Your Current Cart Total: $10.10 You have 21 aisles left to visit. Please plan ahead to stay within your BUDGET: $ 80 With Tartar Control Toothpaste - 6oz regular tube - e. Brand urn Price Choice Aim $2.09 0 Aquafresh $2.79 0 Colgate $2.58 @ Crest $2.69 Q Dental Care $2.89 0 no purchase 0 Please make your choices carefully. You input is important to our research. 44 Figure B-7: Questionnaire - Personal Preference Sample Questions Free Shopping For the following 30 categories, shop as if price were not a consideration. 1. 1/2 Gallon Milk: O Hood 0 Beatrice 0 Sealtest183 0 Garelick Natural 0 West Lynn Creamery 0 none 2. l6oz Box of Pasta: O Barilla 0 Prince 0 President's Choice 0 Ronzoni 0 Mueller's 0 none 3. Toothpaste - 6oz regular tube: O Aquafresh 0 Colgate 0 Aim 4 Dental Care Q Crest 0 none 4. 100 Regular Tea Bags: O Lipton 0 Red Rose 0 Salada ® Twinings 0 Tetley 0 none 5. Packaged Bread (16 oz packaged): O Country Kitchen Cl Arnold's 0 Bouyea Fassetts 0 J.J.Nissen C Wonder ()none 6. Paper Towels - I Roll: o Scott 0 TopCrest 0 Kleenex 0 Bounty 0 Cottonelle ) none 7. 26oz Pasta Sauce Jar/Can: O Prego C Classico ( Hunt's 0 Healthy Choice of Ragu 0 none 8. Chocolate Chip Cookies (- 8oz): O Chips Ahoy-Nabisco 0 Chips Deluxe-Keebler 0 Pepperidge Farm 0 Famous Amos o President's Choice 0 none 9. Detergents - Liquid or Powder(-50oz): o All 0 Xtra 0 Tide 0 Cheer 0 Wisk 0 none 10. Disposable Cups (20ct): o Dixie C Dart 0 Royal Chinet C)Top Crest 0 Solo () none 11. Flavored Chips - Large Bag(~ Ooz): O Lays Chips 0 Wise Potato Chips C) Sun Chips * Doritos 0 Ruffles Chips 0 none 12. Orange Juice (-64oz): 0 Veryfine C Minute Maid 0 Tropicana C Dole 0 Floridas Natural 0 none 27. Coffee (~12 oz can): C Chock Full of Nuts 0 Hills Brothers Colombian C Maxwell House 0 Eight O'Clock 0 Folgers 0 none 28. Cranberry Juice (-48oz): 0 President's Choice * NorthLand 0 Ocean Spray 0 Seneca 0 V8 Splash 0 none 29. Yogurt (-8oz): C Dannon C Stonyfield Farm 0 Columbo 0 Breyers 0 Yoplait C none 30. Mayonnaise (~16oz): o Kraft 0 Hellmann's 0 Bright Day * Cain's 0 Master Choice 0 none 45 Figure B-8: Questionnaire - Shopping Background Questionnaire 1. Do you regularly shop for groceries online? Yes No Approximate number per year: E 2. Do you regularly shop for other non-grocery products online? Yes No Approximate number per month: (~] 3. Have you participated in any on-line experiment before? Yes No If so, approximately how many? >= 5 3 to 5 =< 2 4. Other comments: Methods of receiving your rewards:Pick up in personInterdepartmental mailNone, I am voluntary Please provide your name and address for interdepartmental mailing: 46 Appendix C Categories and Products 47 Table C.1: The Most Popular Products at LaVerdes - Part I Categories Candy Canned Vegetables Cereals Chips and Snacks Coffee and Tea Cookies and Crackers Condiments Popular Products Snickers Milky Way Snack 3 Musketeers Snack Reese's Peanut Butter Cups M+M Plain Candy M+M Peanuts Candy Del Monte Corn Del Monte Green Beans Del Monte Peas Green Giant Niblets Corn Size 13 oz 13 oz 13 oz 13 oz 16 oz 16 oz 15 oz 15 oz 15 oz 11 oz Cheerios - General Mills 15 oz Kellogg's Corn Flakes Kellogg's Raisin Bran Kellogg's Frosted Flakes Kellogg's Rice Krispies Pringles Chips Lays Chips Ruffles Chips Doritos Wise Potato Chips Maxwell House Instant Coffee Maxwell House Instant Coffee Maxwell House Coffee Chock Full 0 Nuts coffee Salada Tea Bags Chips Ahoy Oreo Triscuts Crackers Wheat Thins Crackers Ritz Crackers Fig Newtons Heinz Ketchup French's Mustard Hellmann's Mayo Cains Mayo Daily Pickle Spears 18 oz 20 oz 20 oz 13.5 oz 7 oz 7 oz 7 oz 7 oz 7 oz 8 oz 4 oz 13 oz 13 oz 100 ct 18 oz 20 oz 8.5 oz 10 oz 16 oz 16 oz 36 oz 16 oz 16 oz 16 oz 24 oz 48 Table C.2: The Most Popular Products at LaVerdes - Part II Dairy Milk 1/2 Gallons Land-o-Lakes Butter Detergents Philadelphia Cream Cheese Colombo Yogurt Tide Liquid Tide Powder All Liquid Cheer Liquid Clorox Bleach Joy Dish Liquid Ivory Dish Liquid Irish Spring Ivory Soap Ivory Liquid Hand Soap Stouffer's Entrees Stouffer's Entrees Healthy Choice Dinners Celeste Cheese Pizza Eggo Waffles Lender's Bagels 8 oz 8 oz 50 oz 33 oz 50 oz 50 oz 64 oz 40 cf 14.7 oz 14.7 oz 5 oz 4 pack 7.5 oz 10 oz 11 oz 11 oz 6 oz 12.3 oz 12 oz Green Giant Veggies 16 oz Mott's Apple Juice Ocean Spray Cranberry Juice Veryfine Apple Juice Veryfine Apple Juice V-8 Juice Tropicana O.J. Snapple Nantucket Nectars Gatorade Gatorade Arizona Teas 64 oz 64 oz 64 oz 10 oz 48 oz 1/2 Gallons 16 oz 17.5 oz 32 oz 20 oz 16 oz Veryfine Juices 16 oz Bounce Fabric Softener - Sheets Dish and Hand Soaps Frozen Foods Juices Single Serve Juices 49 Table C.3: The Most Popular Products at LaVerdes - Part III Ice Cream Ben and Jerry's Haagen Daz Breyer's Brigham's Ice Cream Sandwiches Health and Beauty Care Advil Aim Toothpaste Pantene Shampoo Gillette Deodorant Secret Deodorant Pasta and Sauces Prince Spaghetti Prince Elbows Prince Ziti Prince Rotini Prego Spaghetti sauce Ragu Spaghetti Sauce Kraft Parmesan Cheese Soups Campbell's Chicken Noodle Campbell's Cream of Mushroom Campbell's Vegetable Beef Campbell's Tomato Soup Ramen Dry Noodles Paper Goods Bounty Towels Cottonelle Bathroom Paper Kleenex Facial Tissues Scott Napkins Kleenex Facials Plates, Cups and Wraps Dixie Plates Solo Cups Styrofoam Cups Reynolds Warp Glad Trash Bags Water Poland Springs Poland Springs Poland Springs 50 1 Pint 1 Pint 1/2 Gallons 1 Quart 12 ct 24 ct Tablets 6 oz 13 oz 2 oz 2 oz 16 oz 16 oz 16 oz 16 oz 26 oz 26 oz 8 oz 10.7 oz 10.7 oz 10.7 oz 10.7 oz 3 oz 1 Jumbo Roll 4 Pack 175 ct 50 ct 250 ct 48 ct 20 ct 51 ct 25 ft 10 ct 1.5 Liter 1 Liter 2.5 Gallons Table C.4: 30 Categories by Fraction-of-Nines Fractions-of-Nines 1.00 0.75 0.50 0.25 0.00 Categories/Aisles 48 oz Bottled Juices Canned Vegetables - 15 oz Categories/Aisles Bread - 16 oz Packaged Paper Towels Jumbo Roll 16 oz Bag of Pasta Shampoo - 13 oz Corn Flake Cereal 18 oz Chocolate Chip Cookies - 18 oz Toothpaste - 6 oz Water - 1 L Bottle Dishwashing Soaps - 15 oz Liquid Ice Cream - 1/2 Gallons Jam or Jellies - 10 oz Liquid Detergents - 50 oz Milk - 1/2 Gallons Trash Bags - 10 ct Coffee - 12 oz Can Tea - Regular 100 ct Frozen Entrees - 11 oz Soup - Ready-to-Serve 10 oz Can Yogurt - 8 oz Mayonnaise - 16oz Orange Juice - 64 oz 100% Natural Ice Cream - 1 Pint Cereal - approx 16 oz 16 oz Box of Pasta Cups - 20 oz Potato Chips - 10 oz Large Bag Plates - 48 ct Spaghetti Sauce - 26 oz Jar 51 Appendix D Figures 52 Average Time per Aisle - Walkins 3 2.5 a) 0 C a) 1.5 a) .0 E .1 z 0.5 0 3 10 8 20 22 14 16 18 12 Average Time Spent on a Purchase/No-Purchase (sec) 24 26 Total Number of Aisles Visited - Walkins 4 S3 0 a.02 I I E zi1 0 16 18 20 26 24 22 Total Number of Purchase/No-Purchase Figure D-1: Frequency Histograms of 25 Walk-ins 53 28 30 32 Avergae Time Spent per Aisle Visited - 493 Subjects 40 -T-300 a) 0 20- E z 10- 0 - 20 15 10 Average Time Spent on a Purchase/No-Purchase (sec) 5 25 Total Number of Aisles Visited - 493 Subjects 50 a) 40CL 0 a) 30 - CL .0 E z 20 10 0 " 16 18 20 26 22 24 Total Number of Purchase/No-Purchase Figure D-2: Frequency Histograms of 493 Subjects 54 28 30 Bibliography [1] Eric Anderson and Duncan Simester. $9 endings: Why stores sell more at $49 than at $44. Working Paper, October 1999. [2] Joan Ginise. Does psychological pricing really work? a test using scanner data. Master thesis, MIT, Sloan School of Management, 1987. [3] Kent B. Monroe and Angela Y. Lee. Remembering versus knowing: Issues in buyers' processing of price information. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27(2):207-225, 1999. [4] Li Ouyang. An online shopping study. Master thesis, MIT, Operations Research Center, May 1998. [5] Li Ouyang, Robert Zeithammer, and John D.C. Little. Modeling the impact of nine-ending pricing on consumer choice. Working Paper, July 1999. [6] Robert M. Schindler. Symbolic meanings of a price ending. Advances in Consumer Research, 18:794-801, 1991. [7] Robert M. Schindler and Thomas M. Kibarian. Increased consumer sales response though use of 99-ending prices. Journal of Retailing, 72(2):187-199, 1996. [8] Mark Stiving and H. Rao Unnava. How consumers process price endings: A cost of thinking approach. Paper under second review at Journal of Marketing Research, 1999. [9] Mark Stiving and Russel S. Winer. An empirical analysis of price endings with scanner data. Journal of Consumer Research, 24:57-67, June 1997. 55 [10] Robert Zeithammer. Effects of price-endings on consumer choice: 9-ending meaning effect as an artifact of perception and categorization. Term Paper, January 2000. 56