Monolithic RF Frontends for Ubiquitous ... Connectivity Sushmit Goswami

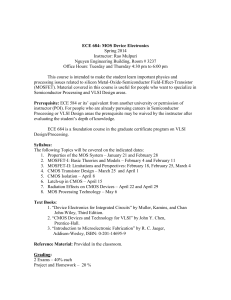

advertisement

Monolithic RF Frontends for Ubiquitous Wireless

A-CHNES

Connectivity

MASSACHUSETTSINSETt

OF TECHNOLOGY

by

Sushmit Goswami

APR

B. E., University of Delhi (2005)

M. S., Arizona State University (2007)

0 2014

-IBRARIES

Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer

Science

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

February 2014

© Massachusetts

Institute of Technology 2014. All rights reserved.

Author ..................................................

Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

A01

January 31, 2014

Certified by..

If

Certified by............

Joel L. Dawson

Associate Professor of Electrical Engineering

Thesis Supervisor

.....

..

..

...

. ..

.

Hae-Seung Lee

Professor of Electrical Engineering

Thesis Supervisor

,

Accepted by ..............

--Leslie A. Kolodziejski

Professor and Chair, Department Committee on Graduate Students

1

2

Monolithic RF Frontends for Ubiquitous Wireless

Connectivity

by

Sushmit Goswami

Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

on January 31, 2014, in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

Abstract

The desire for ubiquitous connectivity is pushing radios towards highly-integrated,

multi-standard and multi-band implementations. This thesis explores architectures

for next-generation RF frontends, which form the interface between the RF transceiver

and antenna. RF frontend performance has important implications for the energy

efficiency, frequency range and sensitivity of the radio.

Ubiquitous connectivity requires bringing online previously unconnected, closedcircuit systems. Case in point, the recently ratified 802.11p standard targets wireless

access in vehicular environments. The first part of this thesis presents an RF frontend

for 802.11p applications. Gallium Nitride is used as an enabling technology platform

for monolithic integration of high-power RF functions. A number of architectural

techniques are proposed to enhance energy efficiency.

Even in relatively mature use cases like smartphones, significant evolution is

needed to address future needs. Emerging wireless standards specify dozens of bands

covering several octaves for worldwide connectivity, which need to be supported with

a single device. However, in current multi-band radio implementations, significant

redundancy is still the norm in the RF frontend. In the second part of this thesis,

an improved architecture for multi-band, time-division duplexed radios is introduced,

which replaces multiple narrowband frontends with a frequency-agile solution, tunable over a wide frequency range. A highly digital architecture is adopted, leading

to a fully integrated solution wherein both efficiency and achievable frequency range

benefit from CMOS scaling.

Thesis Supervisor: Joel L. Dawson

Title: Associate Professor of Electrical Engineering

Thesis Supervisor: Hae-Seung Lee

Title: Professor of Electrical Engineering

3

4

Acknowledgements

I must begin by thanking my parents and sister for their unconditional love and

support for all my endeavors. Over the years, they have sacrificed much to ensure I

had the best shot at all that is worthwhile. Any achievement, however big or small,

is as much theirs as it is my own.

I am grateful to Prof. Joel Dawson for offering me a position in his group back

in 2010, and thereby facilitating my transition from industry to MIT. From the very

beginning, he was incredibly supportive of my ideas, and let me define my own research problems. I consider the opportunity to work with him a privilege and a truly

enriching experience.

I thank Prof. Harry Lee for supporting me for the latter part of my journey at

MIT, and letting me continue my research in RF. His expertise in ADC design is

truly phenomenal. I also had the pleasure of serving as a teaching assistant for him

and learned a lot from his experience as an instructor.

Prof. Anantha Chandrakasan's contribution to the completion of my studies extends far beyond just being on my committee. His unwavering commitment to supporting students in any way possible, regardless of group affiliation is a source of

inspiration to me. He facilitated my transition from one research group to another,

and generously allowed me to test in his lab despite the busy schedule of his own

students.

Prof. Li-Shiuan Peh provided financial support to start a new project with NTU

Singapore, for which I am grateful. At NTU Singapore, Dr. Pilsoon Choi served as

an active collaborator with me. I thoroughly enjoyed working with him.

Prof. Charlie Sodini generously gave me a desk in his lab area without me having

any affiliation with his group, for which I am grateful. I also thank him for free Red

Sox tickets.

The Advanced Concepts Committee at MIT Lincoln Lab (LL) provided financial

support for one of my projects. In particular, I would like to thank Dr. Helen Kim

for championing the research proposal and seeing it through the committee. Helen

5

went much beyond playing a sponsor-observer role. She made available additional

resources from LL to actively support me, without which the project would not have

succeeded. At LL, special thanks also to Dan Baker, Karen Magoon, Peter Murphy

and Jake Zwart.

At MIT, I have had the privilege to interact with many exceptional students.

Among them, there are two who directly impacted the work that I have done. Philip

Godoy built up the test infrastructure for outphasing from the ground up at MTL. His

board layouts and test setup served as reference designs for me, saving me valuable

time. Sungwon Chung has helped me constantly over the years, by patiently answering my questions and resolving a multitude of issues in the lab. Special thanks also to

Nachiket Desai, Michael Georgas, Pat Mercier, Phil Nadeau, Arun Paidimarri, Rahul

Rithe, Gilad Yahalom and Marcus Yip for many engaging technical, non-technical

and philosophical discussions.

I will conclude by saying that having attended three different universities, MIT

EECS is by far the most student friendly department I have come across anywhere.

Long live Course VI.

6

Contents

17

1 Introduction

1.1

2

3

Overview of state-of-the-art mobile radios

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

19

. . . . . . . . .

19

1.1.1

RF transceiver

1.1.2

RF frontend . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

19

1.2

Research contributions . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

22

1.3

Thesis organization . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

24

25

Challenges in RF Frontend Design

2.1

Monolithic integration . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . .

25

2.2

Energy-efficient operation

. . . . . . . . .

. . . .

28

2.3

Multi-octave frequency coverage . . . . . .

. . . .

31

35

A High-power GaN RF Frontend for Vehicular Connectivity

36

3.1

IEEE 802.11p . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3.2

GaN: An enabling technology for monolithic high-power RF integration 37

3.3

Proposed architecture . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

38

3.4

3.5

3.3.1

Performance impact of TX/RX switch

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

38

3.3.2

Modified switching scheme . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

39

TX design . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ..

.

. . .. .

.. .

41

3.4.1

GaN Class-AB efficiency analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

42

3.4.2

Dual-bias linearization . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

45

3.4.3

Matching networks and circuit implementation . . . . . . . . .

46

RX design . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

50

7

3.5.1

RX switch . . . . . . . . . . . .

50

3.5.2

Low noise amplifier (LNA) ...

51

3.6

Physical design . . . . . . . . . . . . .

54

3.7

Measurement results . . . . . . . . . .

55

3.7.1

Small-signal response . . . . . .

55

3.7.2

TX large-signal response . . . .

55

3.7.3

TX modulated tests......

58

3.7.4

RX large-signal response . . . .

58

3.8

Comparison with other published work

61

4 A Frequency-agile RF Frontend for Multi-band TDD Radios in 45nm SOI CMOS

4.1

63

Conventional multi-band TDD archit

ctu.1

re

64

..

.... .. ...

4.2

Proposed frequency-agile architectur

65

4.3

TDD operation and proposed TX/R X switching scheme .

67

4.4

Target frequency range . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

69

4.5

TX design . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

70

4.5.1

PA unit cell . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

70

4.5.2

Core architecture . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

74

4.5.3

Top-level architecture . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

77

4.5.4

Embedded TX switching

. . . . . . . . . . . .

81

RX design . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

83

4.6.1

RX switch . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

84

4.6.2

Gain and power scalable LNA . . . . . . . . . . .

86

4.6.3

Noise analysis . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

88

Design of RF passives . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

91

4.7.1

Choice of component values . . . . . . . . . . . .

91

4.7.2

Transformer based power com ibiner . . . . . . . .

93

4.7.3

Digitally tunable capacitor bEnk . . . . . . . . . .

96

4.7.4

Tunable matching network efficiency

99

4.6

4.7

8

4.8

4.9

Impact of CMOS scaling

100

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

4.8.1

Achievable frequency range

4.8.2

PA instrinsic efficiency . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

101

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

Layout, ESD and packaging

4.10 TX measurements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106

4.10.1 TX mode setup . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

108

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

110

4.10.4 Static outphasing response . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

111

4.10.2 Turn on/off transients

4.10.3 Continuous-wave (CW) performance

4.10.5 Modulated signal performance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 113

4.11 RX measurements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 115

4.11.1 RX mode setup . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 115

4.11.2 Small-signal measurements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

115

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

117

4.12 Performance comparison and conclusions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

118

4.11.3 Third-order intercept test

4.12.1 Comparison with state-of-the-art CMOS PA's . . . . . . . . . 118

4.12.2 Comparison with state-of-the-art CMOS RF frontends

5

. . . . 121

123

Conclusion

5.1

Sum m ary of results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

123

5.2

Future w ork . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

124

A List of Abbreviations

127

B Transformer Analysis and Modeling

129

B.1 Transformer equivalent circuits

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 129

B.2 Impedance transformation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

130

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

131

B.3 Lumped model extraction

C Outphasing Control Law

133

D List of RF Test Equipment

135

9

10

List of Figures

1-1

Key components of the RF frontend . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1-2

Radio classes: (a) Time division duplexing or TDD (b) Frequency

20

division duplexing or FDD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

21

1-3

High-power GaN RF frontend architecture . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

22

1-4

Frequency-agile RF frontend architecture for multi-band TDD radios

23

2-1

RF frontends employing (a) Heterogenous integration with multiple

IC's (b) Monolithic or single-chip integration . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

26

2-2

PA topology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

27

2-3

Asymptotic efficiency limits of different PA architectures

. . . . . . .

30

2-4

Resonant RF amplifier chain (a) Fixed (b) Tunable . . . . . . . . . .

32

2-5

Conventional multi-band RF frontend employing hardware redundancy

to cover multiple bands . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

34

3-1

802.11p use-cases . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

36

3-2

Performance impact of TX/RX switch (a) TX mode (b) RX mode . .

38

3-3

Impact of TXSW loss on energy consumption

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

40

3-4

Proposed GaN RF frontend (a) TX mode (b) RX mode . . . . . . . .

41

3-5

IV characteristics of a reference GaN power transistor . . . . . . . . .

43

3-6

Class-AB efficiency limits compared for CMOS, SiGe and GaN processes 45

3-7

Composite Class-AB/C transconductor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

46

3-8

Dual-bias linearization of large-signal transconductance . . . . . . . .

46

3-9

Load-pull setup . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

47

3-10 PA schem atic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

49

11

. . .

51

. . .

52

. . .

53

3-14 Die micrograph . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

54

3-15 RF frontend frequency response . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

55

3-16 Dual-bias linearization . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

56

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

57

3-18 TX saturated power and efficiency over frequency . . . . . . . . . . .

58

3-19 Power sweep with 20MHz BW OFDM signal at 5.875 G Hz . . . . . .

59

3-20 TX performance with OFDM signal at -25 dB EVM . . . . . . . . . .

59

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

60

3-11 RX switch schematic showing TX mode waveforms

3-12 Transconductor with inductive degeneration

[44]

.

3-13 LNA schematic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3-17 TX power sweep

3-21 Rx large-signal measurements

4-1

Conventional multi-band RF frontend architecture . . . . . .

65

4-2

Proposed RF frontend architecture

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

66

4-3

Radio duplexing schemes (a) Time division duplexing or TDD (b) Frequency division duplexing or FDD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

67

4-4

Proposed TX/RX switching scheme (a) TX mode (b) RX mode . . .

69

4-5

Class-D PA unit cell in both TX mode RF switching states . . . . . .

71

4-6

Simplified electrical model of the PA unit cell . . . . . . . . . . . . .

72

4-7

Outphasing PA core (a) Implementation (b) Equivalent electrical model

at fundamental frequency

4-8

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

PA tunable matching network (a) Simplified electrical model (b) Actual

im plem entation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4-9

75

78

TX architecture: (a) Class-D PA unit cell (b) Outphasing PA core (c)

Tunable matching network . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

80

4-10 Embedded TX switching (a) PA unit cell in RX mode (b) Impact of

parasitic capacitance loading on RX signal path . . . . . . . . . . . .

82

. .

83

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

85

4-13 Complimentary gm cell response showing superposition of gm,, and gmp

87

4-11 RX architecture (a) RX switch (b) Gain and power scalable LNA

4-12 HVS off state operation details

12

4-14 LNA small-signal model including noise sources . . . . . . . . . . . .

89

4-15 Transformer based power combiner details . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

94

4-16 Transformer parameters extracted from EM simulation . . . . . . . .

96

4-17 CTUNE implementation details . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

97

4-18 Designed value of CTUNE vs. FCW . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

98

4-19 Tunable matching network - Efficiency and power factor vs. FCW . .

99

4-20 Impact of CMOS scaling on achievable frequency ratio (4 = 3.77 x 10")101

4-21 Impact of CMOS scaling on PA unit cell efficiency (v = 0.15)

. . . .

103

4-22 Die m icrograph . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105

4-23 Custom two-stage RF package details (a) Ceramic (Al 2 03) package

with flip-chip IC attachment (b) Rogers R04350B PCB . . . . . . . . 106

4-24 TX mode experimental setup

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

107

= 1.7 GHz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 108

4-25 TX step response at

fRF

4-26 TX step response at

fRF =

3.4 GHz . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 109

4-27 TX continuos-wave measurements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110

4-28 Normalized output power and efficiency vs. power control word (PCW) 112

4-29 Outphasing TX performance with 20 MHz, 64-QAM modulated signals

with PAPR = 5.2 dB . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114

4-30 RX mode experimental setup

4-31 Frequency Response

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 115

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

116

4-32 LNA small-signal measurements - Av: Voltage gain, NF: Noise figure,

lIP 3 : Input-referred third order intercept . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 117

4-33 LNA two-tone power sweep for IIP3

GHz .........

- fRF1

= 1.79 GHz,

fRF2

= 1.81

....................................

118

4-34 Comparison with state-of-the-art CMOS PA's; JSSC - [22] [53] [63]

[72]; TMTT - [73] [74]; ISSCC - [45] [52] [71] [75] [76]; ISSCC (3dB) [13] [14] [70] (these papers report 3 dB BW instead of 1dB) . . . . . .

120

B-1 Transformer equivalent circuit models . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 129

B-2 Transformer impedance transformation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 130

13

C-1 Outphasing vector representation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

14

133

List of Tables

3.1

Physical properties of various semiconductors

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

37

3.2

PA impedances at fundamental frequency . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

48

3.3

PA component values . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

49

3.4

LNA component values . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

53

3.5

TX CW performance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

57

3.6

TX performance comparison with other fully integrated solutions

. .

61

4.1

Capacitor slice simulation results

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

98

4.2

Tunable matching network - Performance at feff vs. ft

4.3

TX performance in multiple LTE bands for 64-QAM, 20 MHz signals

. . . . . . . 100

with PAPR=5.2 dB . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 113

4.4

Performance comparison with other published TDD RF frontends. . .

15

121

16

Chapter 1

Introduction

By some estimates [1], the wireless industry reached a critical juncture in 2013 in that

the number of mobile, internet-connected devices exceeded the world's population.

This explosive growth in devices has been possible due to the maturation of several

enabling technologies, principal among them being the highly integrated radio. Even

after decades of work, radio design continues to be an exciting area of research due to

the continual evolution in existing use-cases and emergence of new paradigms, both

of which bring challenges and opportunities in equal measure.

In the last few years, mobile internet has come of age. Connectivity on the move

is no longer a luxury, but a base feature in most mobile devices sold today. The next

generation of mobile devices (smartphones, tablets etc.) is expected to be faster,

lighter and have longer battery life. Increased mobility of users, as evinced by declining PC sales and a fast-growing mobile market [2], also necessitates that devices offer

uninterrupted connectivity irrespective of location, while sustaining high data-rates to

support cloud-based services. Further, as the industry approaches 100 % penetration

in developed countries, user growth in the future will be mainly driven by developing

countries, which are home to the majority of the 5 billion people worldwide currently

without internet access [3], putting significant price pressure on this market.

Within the present decade, it is anticipated that internet connectivity will also

extend to entirely new classes of devices. Vehicles, parking meters, industrial sensor

nodes, home thermostats, continuous health monitors etc. are all examples of pre17

viously closed-circuit systems that are expected to come online. This proliferation

of connectivity has been termed the internet of things (IoT) [4] [5] [6].

While the

IoT paradigm will rely on both wired and wireless connectivity, the vast majority

of devices which come online will be wireless, computationally lean, battery or self

powered and extremely compact. From the radio designer's perspective, design for

next-generation applications puts forth the following challenges:

" Ubiquitous connectivity cannot become a reality at current price points. Due to

increased price pressure in the mature but still growing mobile device market,

and the emergence of an entirely new one (i.e IoT), further commoditization

of radio hardware is needed. The monolithic (single-chip) radio has been envisioned for many years, and represents the ideal solution from a cost and formfactor standpoint.

However, full integration in low-cost technology remains

elusive.

* Since the vast majority of future wireless systems will be battery or self powered,

with continually shrinking form factors, large reservoirs of energy (high-capacity

batteries or super-capacitors) are not feasible. Therefore, radio systems need

to be more energy-efficient in order to maximize up-time for a given amount of

stored or harvested energy.

" The coexistence of an exponentially growing number of wireless devices requires

the radio system to be more flexible. At any given time, the optimal frequency

band for communication is a function of geographical location, presence of other

similar coexisting devices, data-rate needs and available wireless infrastructure

(access points, routers).

Clearly, radios should support communication over

wide frequency range to enable location agnostic or ubiquitous connectivity.

Radio operation over a wide frequency range conflicts directly with the first

two objectives, and therefore presents a major challenge.

18

Overview of state-of-the-art mobile radios

1.1

Figure 1-1 shows the block diagram of a typical mobile radio system. When partitioned by power level, there are two main subsystems:

RF transceiver

1.1.1

In this work, the term RF transceiver is used to denote the low-power section of the

radio, which includes all the mixed-signal processing that occurs between digital baseband data (commonly represented with IQ pairs) and modulated RF signals. On the

transmitter (TX) side, this involves digital-analog conversion, filtering, up-conversion

to RF carrier frequency and some amplification. On the receiver (RX) side, the signal path performs down-conversion, filtering and analog-digital conversion. Since the

transceiver only comprises low-power circuitry, design has benefitted tremendously

from the scaling of CMOS technology. Increasingly, more and more functionality

has been integrated, while power consumption has gone down. For instance, multistandard transceivers have been demonstrated on a single-chip, both in the form of

multiple dedicated sections [7] and also more ambitious software-defined transceivers

[8], which can be reconfigured to work in one of several different bands at a time.

1.1.2

RF frontend

The RF frontend represents the high-power section of the radio. As shown in figure 11, a typical RF frontend consists of three key components:

1. Power amplifier (PA): The TX signal from the transceiver is not strong

enough to drive the antenna directly. The PA forms the last amplifying stage

in the TX signal path. For instance, WLAN requires a maximum output power

of at least 0.5 W or 27 dBm, which corresponds to 14 Vpp across a 50 Q load.

In addition to the stringent output power specification, PA design is further

complicated by use of linear modulation techniques in modern wireless systems

to maximize data-rates. Generally, it is easy to get high RF PA linearity or

19

(1) RF Transceiver

frx-

Q7X

+--

(2) RF Frontend

f'X

+

PA

OC

IRX '

QRX+

-LN

fRX

Figure 1-1: Key components of the RF frontend

efficiency independently, but very difficult to achieve them simultaneously [9].

Therefore, the PA is the most power hungry component of the radio and its

efficiency largely determines the efficiency of the entire radio system. The choice

of device technology plays a critical role in achievable performance. PA efficiency

and therefore power consumption also suffers if wide bandwidths are desired,

making multi-band design extremely challenging.

2. Low noise amplifier (LNA): The LNA forms the first stage in the RX signal

path and provides enough gain with low noise so that sensitivity is not compromised by the noise of subsequent stages. High linearity is also important

to preserve overall linearity of the RX path, and also for tolerating interfering

signals without corrupting the desired signal.

3. Switch or duplexer: Radios can be divided into two classes. Time-division

duplexing (TDD) radios (figure 1-2(a)) are half-duplex i.e. they time-share the

same frequency for both transmit and receive. On the other hand, frequencydivision duplexing (FDD) radios (figure 1-2(b)) utilize different frequencies to

20

enable simultaneous transmit and receive operation. For TDD, an RF switch

(controlled by the baseband processor) is used to time-multiplex between TX

and RX mode. For FDD, a duplexer is used to tailor the frequency responses

of the TX and RX path to a pair of frequencies defined by the standard, while

sharing the same antenna. Since these components lie directly in the RF signal

path, they also need to handle very high output power, while their loss adversely

impacts performance.

(a)

(b)

C.C

MM

LL

U

Time

TX

Time

Figure 1-2: Radio classes: (a) Time division duplexing or TDD (b) Frequency division

duplexing or FDD

CMOS technology evolution has not benefitted RF frontends to the same extent

as transceivers because breakdown voltages decrease with scaling, making high-power

compatibility more difficult rather than easier. Further, analog-intensive design techniques are still the norm for high-power RF circuits, and performance does not always

benefit from scaling e.g. resonant LC circuits are used extensively, occupy large die

area and do not scale. Discrete solutions using multiple device technologies are still

common. Many of the current technologies in use are expensive and a barrier to

radio commoditization. Finally, much hardware redundancy results from the lack of

compelling multi-band solutions, further increasing area and cost.

To summarize, the key to addressing many of the challenges in radio design now

lie in the RF frontend. In this thesis, new fully integratedRF frontend architectures

suitable for the next generation of wirelessly connected devices are proposed, implemented and evaluated.

21

Research contributions

1.2

The first contribution of this work is a high power RF frontend architecture which

leverages GaN technology. A vehicular connectivity application employing the new

802.11p standard is targeted. Traditionally, RF frontends for high power applications

have relied on discrete components assembled into multi-chip modules. The proposed

ultra-compact and fully integrated architecture is shown in figure 1-3. In addition to

the superior efficiency offered by GaN technology, two architectural techniques are

used to further boost performance. First, part of the TX/RX switch is absorbed

into the PA itself to reduce loss. Second, the PA employs a dual-bias technique for

transconductance linearization. To validate the proposed architecture, a prototype

IC with over 33 dBm output power at 5.9 GHz is demonstrated in GaN technology.

VDDGaN

o/p match

VTRX

LNA

-T

EN

i/p match

VEN

M1

VIN

Vb

M

b2

M1+M2

M2 - class C

Mi - class AB

VIN

PA Core

Figure 1-3: High-power GaN RF frontend architecture

The second contribution of this work is a frequency-agile RF frontend architecture

for multi-band mobile radios. A unified solution for WLAN and TDD-LTE is targeted.

The proposed architecture, which is shown in figure 1-4 eschews traditional narrow22

band analog RF circuits. Instead, both TX and RX signal paths employ broadband

topologies inspired by the CMOS inverter. The frequency response of the system is

digitally tunable over a wide range. Therefore, multiple narrowband frontend components can be replaced by this minimalistic and flexible solution. To validate the

proposed architecture, a prototype IC with over 27 dBm output power and a target

frequency range exceeding 1.8 - 3.6 GHz is demonstrated in SOI CMOS technology.

Multi-band

Antenna

Transceiver

Reciprocal

Harmonic

Filter

FCW

(Freq. Control Word)

H(f)

f

fRF=f(FCW)

Figure 1-4: Frequency-agile RF frontend architecture for multi-band TDD radios

The RF frontend architectures presented in this thesis are specific to TDD standards. Therefore, this work only considers integration of the TX/RX switch. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that techniques introduced herein for PA efficiency enhancement and frequency-agile design are generally useful to any class of radio (TDD

or FDD).

23

1.3

Thesis organization

This thesis is organized as follows. Chapter 2 discusses in more detail key challenges

in the design of RF frontends for the next generation of wirelessly connected devices.

Chapter 3 and 4 present the theory, design, implementation and measurement results

of the two RF frontend prototypes introduced in the previous section. Finally, this

work is put into perspective in chapter 5, wherein key contributions are summarized

and a few directions are proposed for future work.

24

Chapter 2

Challenges in RF Frontend Design

As highlighted in chapter 1, evolution of the RF frontend is essential for realizing

radios suitable for the next generation of wireless devices. In this chapter, principal

design challenges are discussed in detail, and relevant prior art discussed to better

differentiate the work detailed in chapters 3 and 4.

2.1

Monolithic integration

RF frontends require simultaneously high-power and high-frequency operation, thereby

posing the one of the last hurdles towards monolithic integration. Traditionally, RF

frontends have utilized heterogenous integration in the form of a multi-chip module,

wherein each component is designed in the most optimal technology. Figure 2-1(a)

shows a typical TDD example, while the desired evolution to a single-chip solution is

shown in figure 2-1(b). Monolithic integration has the following potential benefits:

" Cost: Integration on a single-chip, particularly on a CMOS platform, is typically much cheaper than fabricating two or three different chips.

Further,

packaging cost is also minimized.

* Form factor: Single-chip solutions have smaller weight and volume than multichip modules.

25

* Performance: Tight integration of RF frontend components reduces interconnect loss.

(b)

(a)

--

PA

LNA

PA

vT

-<N

CMOs

Figure 2-1: RF frontends employing (a) Heterogenous integration with multiple IC's

(b) Monolithic or single-chip integration

For moderate power (up to 30 dBm) mobile applications, CMOS technology is especially attractive due to its low-cost, continued scaling and compatibility with mostly

digital transceiver circuitry. However, CMOS integration of RF frontend components

poses challenges, particularly for the PA and TX/RX switch.

Figure 2-2 shows an idealized PA topology. The drain inductor provides DCfeed and resonates out device capacitance at the desired RF frequency. The power

extracted from the PA is maximized (saturated) when the RF component of device

current causes the drain to swing over the entire available voltage headroom of 0 to

2 VDD.

This saturated power level is denoted as PSAT. The function of the matching

network is to perform impedance transformation from the antenna impedance Zo to

Ropt for maximum power extraction. Rept can be determined by:

PSAT=

VDD

2ROt

_

VTX

2ZO

(2.1)

Fine-line CMOS technology has a very low rated VDD of about 1 V. At PSAT = 1 W

or 30 dBm, the required R,t is 0.5 Q, corresponding to a transformation ratio ( Z,)

26

VDD

2VDD

Impedance

0

S

Matching

4

VIN 0Ropt

Vrx

ZO = 50 0

Figure 2-2: PA topology

of 100. Implementing such an extreme transformation is challenging. First, the circuit

becomes very sensitive to parasitic resistance in interconnect, an issue exacerbated

by the fact that the PA device is quite large.

Second, when implementing such

circuits with conventional L or 7r impedance matching topologies, component values

become intractable and loss increases unacceptably. The search for alternate matching

networks for CMOS RF power generation that alleviate some of these issues remains

an active area of research, with power combining [10] [11] emerging as a prominent

technique. Above 2 GHz, power levels exceeding 30 dBm have been demonstrated in

CMOS [12] [13] [14].

At the same power level of 1W or 30 dBm, the voltage swing across at VTx is 20

Vpp. Recall from figure 2-1(b) that the TX/RX switch is connected in between the

antenna at the PA/LNA. Such high voltages make the design of the TX/RX switch

also very challenging. In the TX mode, the PA transmits at power levels up to PSAT.

The TX branch switch is on and needs to conduct high RF voltages up to ±10 V

centered at 0 to the antenna ZO. However, in bulk-CMOS technology, the body of the

27

transistor is always at ground, implying that for high power levels drain- and sourcebody diodes can have reverse breakdown during positive voltage excursions, and turnon during negative voltage excursions. The RX branch switch has to block the same

voltage levels, which leads to similar issues. Various body isolation techniques in

bulk-CMOS have been attempted in the past [15] [16], but adequate power handling

and reliability remains a concern. More advanced technologies like GaAs pHEMT

provide inherent isolation but necessitate multiple chips. A more attractive solution is

to use floating-body transistors found in silicon-on-insulator (SOI) technology. While

SOI is marginally more expensive than bulk CMOS, it offers an excellent integration

medium for RF frontends by combining the benefit of scaled CMOS with excellent

RF isolation.

For high-power applications beyond 30 dBm, specially tailored high-power devices,

which offer simultaneously high breakdown voltage, saturation current, transition

frequency and RF isolation are essential. Gallium Nitride (GaN) technology has

emerged as a compelling contender [17] but integration with the CMOS transceiver

remains a challenge. Fortunately, recent research has opened up the possibility of

GaN transistors as an add-on to CMOS wafers [18], which could enable monolithic

integration in the near future.

2.2

Energy-efficient operation

For medium- and long-range communication, the TX section of the RF frontend,

comprising the PA and TX branch switch, remains the most power hungry component

of the radio. Therefore, maximizing TX efficiency goes a long way in maximizing

battery life, or alternately, maximizing communication range on a given power budget.

PA architectures have been surveyed and analyzed extensively in many excellent

references, including [9] [19]. Only a brief, high-level description is provided here for

context. More details are presented in chapter 3 and 4 where appropriate. Figure 2-3

compares the asymptotic efficiency limit of various PA architectures versus power

back-off from peak power. The desire for increased data-rates leads to non-constant

28

envelope or linear modulation schemes with ever increasing peak to average power

ratios (PAPR), typically 6 dB or higher. Essentially, the dynamic range of the transmitted signal is increased in order to pack more information into a given frequency

band. PA architectures fall into two main classes:

* Classic linear architecture: Class-A/B architectures [9] are inherently linear

but suffer from poor efficiency at back-off. Their circuit topology is similar to

the simplified example shown in figure 2-2. Distinction between Class-A and

Class-B stems from the conduction angle of the active device over the RF cycle,

which is 27r (always on) and ir (on half the time) respectively, and controlled by

the gate bias voltage. Class-B improves efficiency at the cost of linearity. As

shown in figure 2-3, efficiency at 6 dB back-off is only 12.5 % and 39 % for ideal

Class-A and Class-B amplifiers, respectively. In practical design, it is common

to choose a conduction angle between 27r and 7r and refer to the amplifier as

Class-AB.

" Switch-mode based advanced architectures: To improve efficiency under

high PAPR signal drive, there is a strong push to move from Class-AB to more

advanced PA architectures which promise better efficiency. Most such architectures employ nonlinear switch-mode amplifiers (e.g. Class-D/E/F etc.) at their

core. The output power at any given time is proportional to both the square of

the supply voltage and inversely proportional to the load impedance, but independent of the input amplitude. Therefore, output power is varied or backed-off

either through supply or load modulation techniques. Outphasing [20] is one

promising candidate which can be implemented with both lossy and lossless

combiners. With lossy combiners, efficiency reduces at back-off in proportion

to output power, just like a Class-A PA [21].

Lossless combiners are highly

preferred as the asymptotic efficiency of the architecture is 100 % irrespective

of power back-off due to load modulation, but do not offer impedance isolation

and work best with low output impedance cores like voltage-mode Class-D [22].

Polar modulation [23] is another alternative based on supply modulation with

29

the same constant 100 % asymptotic efficiency characteristic. However, implementing the supply modulator is challenging, particularly for wide bandwidths.

ML-LINC and AMO [24] are hybrids of polar and outphasing which simplify

the supply modulator while improving average efficiency.

100

Pclar/Outphasing (lossless)

90 -

80

Outphasing (lossy)

.

70I

-

60I

50

W

40Class B

30A

20- .Class

10-20

-18

-16

-14

-12

-10

-8

-6

-4

-2

0

Back-off from peak power (dBr)

Figure 2-3: Asymptotic efficiency limits of different PA architectures

For moderate power levels up to 30 dBm, CMOS technology represents an attractive but very challenging medium for efficient and linear PA design. The extreme

impedance transforms required to extract power from low voltages (see section 2.1)

lead to high-Q matching networks or power combiners which are lossy when implemented on conductive deep sub-micron CMOS substrates [11]. On the other hand,

the level of integration possible in CMOS is unrivaled and can enable new architectures with better efficiency. The key lies in exploring architectures that leverage the

strengths of CMOS and overcome the weaknesses. Best-in-class GHz-range Class-AB

30

CMOS PA's report peak efficiencies around 40 % [12]. The theoretical promise of

switching based architectures is tremendous, and there has been a lot of interest in

moving to advanced architecture like polar, outphasing and variants thereof. Interestingly, the peak efficiencies of GHz-range switching CMOS PA's is degraded by

practical issues such as matching network and switching loss, and generally not much

better than their Class-AB counterparts [25] [26]. However, the real promise of these

switching architectures is in boosting average efficiency when driven by modulated

signals, where they outperform Class-AB solutions by about 1.5 - 2.0 x.

For high power levels beyond 30 dBm, new materials such as GaN promise higher

efficiency and power density but cannot support complicated efficiency enhancing

architectures on a single-chip until hybrid GaN-CMOS platforms [18] become feasible.

Therefore, more research into minimalistic architectures, which completely integrate

all matching elements on-chip while achieving competitive efficiency and linearity is

needed.

Finally, it is worth mentioning here that TX branch switch loss should be included

when optimizing for overall TX efficiency. This aspect is given detailed treatment in

section 3.3.1.

2.3

Multi-octave frequency coverage

The number of frequency bands and wireless standards supported by mobile devices

has steadily risen in the last decade. By revenue, smartphones is the biggest market

[2] and therefore an apt use-case to consider. Most smartphones sold today support

at least the following standards, frequency bands and peak power levels:

" LTE: FDD and/or TDD, 5 - 10 out of over 40 possible bands, anywhere from

0.4 GHz to 3.8 GHz, 30 dBm

* WLAN: TDD, 2.4 - 2.5 GHz and 4.9 - 5.9 GHz, 27 dBm, possibly multiple

antennas and radios for MIMO

" Bluetooth: TDD, 2.4 - 2.5 GHz, 20 dBm

31

Even though the amount of integration and connectivity offered by current devices is

impressive, there are compelling drivers to support even more frequency bands:

" To enable universal phones, eliminating the need to build separate models for

different carriers and countries. For the manufacturer, this implies consolidation

and for the user, true worldwide connectivity.

* To make phones communicate with new classes of devices, such as those coming

online through the IoT paradigm e.g. Medical implant communications services

(MICS) band (402 - 405 MHz).

" To support MIMO in more bands with the same amount of hardware.

Unfortunately, the notion of RF circuits operating over a wide frequency contradicts well established design techniques. Figure 2-4(a) shows a generic multi-stage

RF amplifier chain. Typically, each stage employs a resonant circuit to counteract

device capacitance to achieve gain.

(h~

VDD

VDD

VDD

VDD

Vb2

Vb2

VbI

VbI

Figure 2-4: Resonant RF amplifier chain (a) Fixed (b) Tunable

A natural extension of the conventional approach leads to tunable RF circuits,

as shown in figure 2-4(b). Such circuits are indeed feasible for low-power circuitry,

32

and make up building blocks for many multi-standard CMOS transceivers [27] and

transceiver blocks [28] [29]. More recently, CMOS RX design has evolved to the point

that a filter-less solution for multi-band applications now appears in sight [30].

Unfortunately, when RF frontend integration (including a high-power TX) is considered, power levels are high enough that tunable passives with good RF performance

are not trivial to implement. With digital tuning schemes the switches used to implement tunable capacitors and/or inductors face the same issues as the TX/RX switch

at high-power levels. Similarly, analog tuning elements such as varactors perform

well only at low power levels. Indeed, all the CMOS PA research cited in sections 2.1

and 2.2 is focused on single-band operation. Due to limitations of current design

techniques, most current multi-band RF frontends employ a "brute force" approach

to multi-band coverage. Figure 2-5 shows a tri-band radio example, covering three

bands centered at fi,

f2

and

f3.

For each band, dedicated circuitry is employed and

switched in and out as needed. Since only one band per radio is active at a time, this

architecture is not area and cost optimal. Tri- and dual-band PA arrays reported in

[31] [32] [33] follow this concept, so do the more complete radio implementations found

in [34] [35]. To the best of the author's knowledge, there are currently no monolithic

high-power RF frontends tunable over multiple octaves in any CMOS technology.

Clearly, alternate design techniques need to be explored to enable more minimalistic

and flexible architectures.

33

Narrowband PA's

SP6T

TXEN2

Multi-band

Antenna

t r nsceiver

RX EN1

- TrasNarvr

L>N'

o bnf2 RXEN2

RXEN3

Narrowband LNA's

Figure 2-5: Conventional multi-band RF frontend employing hardware redundancy

to cover multiple bands

34

Chapter 3

A High-power GaN RF Frontend

for Vehicular Connectivity

The vision of ubiquitous connectivity requires bringing online previously isolated,

closed-circuit systems. One of the more interesting use-cases pertains to vehicles.

Modern automobiles include sophisticated electrical systems comprised of a vast array of sensors and actuators connected to a central computer. Sensors track vehicle

location, speed, tire pressure, collision damage and image the environment in realtime; while actuators control locks, brakes, airbags and front/rear power distribution.

Pushing sensor data into the cloud in real-time for contextual feedback enabled by

tight integration with traffic signaling and map databases has the potential to fundamentally change transportation. Indeed, it is anticipated that vehicular connectivity

will not only have implications for enhancing road navigation and safety [36], but will

also be an integral part of future paradigms like self-driving cars [37].

This chapter presents the design of an RF frontend for the recently ratified 802.1lp

standard, which aims to bring dedicated wireless connectivity to vehicles. As discussed in chapter 2, high-power RF frontends have traditionally relied on multi-chip

modules or discrete designs. The prevailing theme of this chapter is the interplay

of emerging technology and architecture, which enables monolithic high-power RF

integration. With a fixed power budget, maximizing energy efficiency is important

to enhance communication range, which is especially important for vehicles. The im35

provement in baseline energy efficiency by leveraging GaN is theoretically quantified.

In addition, system energy efficiency is further enhanced through two architectural

techniques: (a) A modified TX/RX switching scheme (b) Dual-bias linearization.

Chapter organization is as follows: Sections 3.1 and 3.2 provide a brief overview

of the 802.11p standard and GaN technology, respectively. Section 3.3 introduces the

proposed architecture. Design of the transmitter (TX) and receiver (RX) paths is

discussed in sections 3.4 and 3.5, respectively. Section 3.6 outlines physical design

aspects. Finally, section 3.7 presents measurement results on the fully integrated GaN

IC prototype.

3.1

IEEE 802.11p

802.11p [38], often referred to as wireless access in vehicular environments (WAVE),

is an amendment to the well established and widely used 802.11 (WLAN) standard.

802.11p utilizes a dedicated 75 MHz band from 5.850 to 5.925 GHz in the form of

seven 10 MHz channels with 64-QAM OFDM modulation to support data-rates up

to 27 Mb/s. In the standard, average RF transmit power levels up to 28.8 dBm are

supported.

(a) Vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V)

(b) Vehicle-to-basestation (V2B)

Figure 3-1: 802.11p use-cases

As shown in figure 3-1, both vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) and vehicle-to-basestation

(V2B) scenarios are possible. V2V communication can enhance road safety through

36

downstream multi-hop relay of adverse road conditions or accidents. V2B communication can improve navigation and enable traffic-optimized road signaling to reduce

delay and congestion, in addition to providing dedicated, high-quality internet access

on-the-move.

3.2

GaN: An enabling technology for monolithic

high-power RF integration

The physical properties of several semiconductors including GaN are presented for

comparison in table 3.1 [17].

Property

Si

GaAs

SiC

GaN

Bandgap (eV)

1.1

1.4

3.2

3.4

Critical e-field (MV/cm)

0.6

0.5

3.0

3.5

Charge density (x10 3 /cm 2 )

0.3

0.3

0.4

1.0

Thermal conductivity (W/cm/K)

1.5

0.5

4.9

1.5

Mobility (cm 2 /V/s)

1300

6000

600

1500

Saturation velocity (xlO7 cm/s)

1.0

1.3

2.0

2.7

Table 3.1: Physical properties of various semiconductors

To enable monolithic integration of high-power RF frontends, the adopted device

technology should have the following features:

1. High power density: The breakdown voltage of the technology, in conjunction with current density and thermal conductivity, determines the achievable

power density (Watts/mm). Breakdown voltage also determines the voltage

blocking limit of RF switches. The wide band gap and high critical field of

GaN enable breakdown voltages as high as 150 V, nearly two orders of magnitude higher than fine-line CMOS. Further, the high charge density of GaN

enables current densities as high as 0.8 - 1.5 A/mm, very competitive with

fine-line CMOS. GaN also features excellent thermal conductivity to facilitate

37

heat transfer away from high-power devices to keep junction temperatures reasonably low. Consequently, power densities achievable in GaN are typically

20 - 50x higher than CMOS.

2. High transition frequency (fT): As a rule-of-thumb, the RF operating frequency should be at least a 3 - 5 x lower than fT. The competitive mobility

and high saturation velocities in GaN enable an fT of 20 - 40 GHz for state-ofthe-art devices at breakdown voltages of about 150 V [39], which is sufficiently

high to make GaN an attractive candidate for many RF applications.

3.3

Proposed architecture

The first efficiency enhancement technique proposed in this work is a modified switching scheme that reduces TX mode switch loss. The performance impact of a conventional switching scheme is discussed first in section 3.3.1, followed by an introduction

to the modified switching scheme used in the present work in section 3.3.2.

3.3.1

Performance impact of TX/RX switch

(a)

(b)

POUTPA

--

-+PA

|

PIN

LNA

!_NA

RL,RXSW

Figure 3-2: Performance impact of TX/RX switch (a) TX mode (b) RX mode

As shown in figure 3-2, an explicit series switch is usually employed in both the

TX and RX branches in order to switch modes in a TDD radio. The design of TX

branch switch (TXSW) is particularly challenging as it needs to meet three conflicting

requirements simultaneously:

38

1. High RF power (both voltage and current) handling capability

2. Low insertion loss to minimize TX efficiency degradation

3. High linearity so as to not limit the overall linearity of the TX chain

While switches with adequate power handling and linearity have been demonstrated,

they exhibit high insertion loss of 1 to 2 dB [40] and consume significant die area.

Lossy series elements in the TX RF path (between PA and antenna) are highly undesirable due to the adverse impact on overall TX performance, which can be quantified

with the aid of figure 3-2. If the PA produces an output power of

TXSW has a loss of

PL,TXSW

POUT,PA,

and the

(in dB), then the achievable TX output power and

efficiency are:

( PL,TXSW

POUT = POUT,PA X

7 = nPA

x

10-(

10

10

)

P L,TXSW\

10

(3.1)

(3.2)

Since the PA dominates TX power consumption, the energy consumed by it is:

ETx

POUTPA X

(3.3)

t

77PA

Typically, the total output power from the TX is dictated by the standard, implying that the PA output power has to be boosted to compensate for TXSW loss;

its impact on TX energy consumption can be obtained from equations 3.1 and 3.3:

AErx

ETX

PL,TXSW

_10(

10

- 1(3.4)

ETx

3.3.2

Modified switching scheme

The proposed architecture focused on co-design of the TX and RX paths to essentially

eliminate the explicit switch from the TX branch in order to improve efficiency and

save energy. In mathematical terms, the goal is:

39

PL,TXSW =

(3.5)

0

Equation 3.4 is plotted in figure 3-3, showing that overcoming even 1 dB of loss

dramatically lowers TX energy consumption by 20 %.

100

80-

0

,x60

40

20

0

1

2

3

L,TXSW(dB)

Figure 3-3: Impact of TXSW loss on energy consumption

Figure 3-4 shows the modified GaN frontend architecture in its two modes of

operation. No explicit switch is included in the TX branch. Instead, the drain of the

PA transistors is directly connected to the RX section. Frontend operation can be

understood by considering the two modes of operation in turn:

1. TX mode: In the TX mode, the PA is active. The output matching network

is designed to present the optimum impedance ZL(w) (when loaded by a 50

Q antenna) which extracts maximum power from the GaN power transistor.

Under this condition, the drain of the PA device sees large voltage swings up

to approximately

2 VDD.

The RX branch series-shunt switch (RXSW) isolates

and protects the inactive LNA from this voltage stress.

2. RX mode: In the RX mode, the PA transistors are turned off by employing

a sufficiently large negative gate bias. Under this condition, the PA presents a

small but finite capacitance CO,PA at the drain node. Since the output matching

network is passive, its characteristics do not depend on the operating mode.

The LNA is power matched to the parallel combination of ZL and CO,PA at the

40

RF frequency w to maximize gain and minimize noise figure. In mathematical

terms:

ZX(w)

(a)

=

ZTx(w)*

=

(ZL(w) 11.

)(3.6)

(b)

VDD

PA

==

==

Mx

Zvx

LNA

ZL

t

RXSW

RXSW

Figure 3-4: Proposed GaN RF frontend (a) TX mode (b) RX mode

3.4

TX design

The TX needs to satisfy the conflicting requirements of high output power, efficiency

and linearity simultaneously. Suitability of GaN for high-power applications has already been discussed in section 3.2. In terms of overall TX efficiency, the modified

architecture outlined in section 3.3 provides an advantage. The focus of this section

is the design of an appropriate core PA topology with simultaneously high linearity

and good efficiency suitable for an ultra-compact monolithic solution.

As previously discussed in section 2.2, PA design for non-constant envelope modulation schemes has two major flavors [9]: (a) Class-AB amplifiers which are inherently

linear but somewhat inefficient (b) Switching amplifiers which are inherently nonlinear but very efficient in conjunction with more sophisticated architectures (e.g. EER,

outphasing) to synthesize non-constant envelope waveforms.

In this work, a Class-AB design is chosen because it offers the most compact and

fully integrable solution for a linear PA. While the peak efficiency of Class-AB ampli41

fiers under linear modulation is acknowledged to be somewhat lower than switching

solutions, the features of GaN technology impact Class-AB architectures in a favorable

way for the desired power levels. Efficiency of Class-AB amplifiers in GaN technology

is theoretically quantified and compared to other technologies in section 3.4.1. On

the other hand, switching amplifier based architectures require additional circuitry.

For instance, polar modulation [23] requires a high-voltage supply modulator. Such

circuits are currently not integrable on the same chip as GaN transistors. However, it

is worth noting that with the emergence of platforms for monolithic GaN-CMOS integration [18], more complicated architectures may indeed become feasible in the future.

Finally, in these future technology platforms, efficiency enhancement in the form of

envelope tracking [19] will also be possible on the chosen Class-AB architecture.

3.4.1

GaN Class-AB efficiency analysis

Since Class-AB amplifiers are usually biased quite close to device threshold, the following analysis treats the amplifier as Class-B to arrive at an estimate for GaN Class-AB

PA performance relative to other device technologies. Figure 3-5 shows the simulated

DC I-V characteristics of a reference GaN power transistor. There are primarily two

main loss mechanisms responsible for deviation of Class-B drain efficiency from the

theoretical maximum, denoted here by riB

=

78.5 %:

1. Finite device knee voltage: Linear Class-AB operation requires the transistor to operate as a high output impedance current source. Therefore, the

VDS

across the transistor cannot fall below a certain voltage, denoted as the device

knee voltage VDSAT. The impact of finite knee voltage on efficiency is quantified

by the factor:

VDSAT

(3.7)

VDD

2. Output matching network loss: In order to extract maximum instrinsic

42

2.25-,

21.75

VDSAT

Isat

1.25 1

0.75

0.5

0.25

2

DD%%

0

10

20

40

30

VD(V)

VDD

50

-

VDSAT

60

Figure 3-5: IV characteristics of a reference GaN power transistor

power PSAT,il from the transistor, the antenna impedance ZO has to be transformed to an optimal value R,,t given by:

PSAT,i

(VDD

VDSAT)

Ropt

-

2

(3.8)

From load-line theory [9], an alternate expression for Ropt can also be derived.

RVpt = 2 DD

-

VDSAT

(39)

Isat

Substituting Rept from equation 3.8 gives

'sat,

which can be used to size the

power transistor appropriately. The impedance transformation required to ex'Maximum power extractable with device staying in saturation region, assuming matching net-

work loss is zero.

43

tract maximum power is therefore 2 :

(3.10)

r = Ropt

Zo

Where ZO is typically 50 Q. Further, assuming that the impedance transformation is realized with a single-stage L-match, with the only source of loss being

the finite inductor quality factor QL 3 , the matching network efficiency is [11]:

1

M

r(311)

The overall PA efficiency is therefore:

(3-12)

T7SAT = T7BTKTM

Due to matching network loss, not all of the power extracted from the device reaches

the output. Accounting for this loss, the actual output power realized (in watts) is:

(3-13)

PSAT = 7M PSAT,i

Representative process parameters for three different device technologies are used

to compare the achievable efficiency over a range of power levels.

TK

is independent of

power level and computed from equation 3.7. 7iM is determined by a two-step process.

First, the required r is determined from equations 3.8 and 3.10. Second, a typical QL

value of 15 is assumed to calculate 7iM from equation 3.11.

The achievable efficiency limit is plotted in figure 3-6. The low breakdown voltage

of CMOS and SiGe processes results in extreme downward impedance transforms at

watt-level output power. Consequently, qM suffers4 and lowers the overall efficiency.

2

Usually, Zo will be matched to Z 0 pt(w) = Rpt 1.CA

but the reactance is omitted here for

simplicity

3Up to 6 GHz, quality factor of integrated capacitors is typically much higher than inductor and

can be neglected

4

Some alternate matching techniques do exist that relax the tradeoff between r and r/M [11], but

the argument remains generally valid.

44

In contrast, GaN only requires a moderate transformation for watt-level output power.

At the target power level of 36 dBm (4 W), GaN can offer up to 65 % drain efficiency,

which represents a very favorable starting point for the present design.

8070

60 ---0,o

GaN

- -

---

50-_'

-r<a 40-

SiGe

::30 20- -M

10 -MS

16

18

20

22

24

26

28

30

POUT(dBm)

32

34

36

38

40

Figure 3-6: Class-AB efficiency limits compared for CMOS, SiGe and GaN processes

3.4.2

Dual-bias linearization

While the preceding section illustrates that Class-AB amplifiers in GaN technology

are capable of respectable efficiency, nothing has been said so far about linearity.

Unsurprisingly, the principal source of Class-AB PA nonlinearity is the active device,

which can essentially be modeled as a large-signal nonlinear transconductance which

is dependent on frequency, bias and drive conditions. To balance efficiency and linearity, it is standard practice to bias Class-AB amplifiers close to device threshold [9].

Under such bias conditions, the device exhibits significant compressive nonlinearity

at high drive levels, leading to a lower than desired P1dB point. Since Class-AB amplifiers have to be backed-off from their P1dB point to meet system linearity and/or

EVM requirements, a low PidB point corresponds to lower average efficiency. In this

work, the second key efficiency enhancement technique is to increase the P1dB point

of the PA through cancellation of the compressive nonlinearity with an expansive

counterpart.

As previously demonstrated in [32] [41], compressive nonlinearity in

Class-AB amplifiers can be cancelled by introducing an appropriately sized auxiliary

power transistor biased Class-C with its output current combined in phase with the

45

main Class-AB device. This arrangement is shown in figure 3-7. Figure 3-8 shows

the simulated individual transconductances GmI/Gm2 (Class-AB/C) over a range of

drive voltages, as well as the linearized composite transconductor Gm.

htot

Gmn

v, H G

Gm2

Vb1 (> Vm)

Vb2 (< VmH)

Figure 3-7: Composite Class-AB/C transconductor

0. 12

I.

I

c0.08-

GmG+

Class-AB (G 1)

0.06

C

C0

-30

-20

-10

V. (dBV)

0

10

Figure 3-8: Dual-bias linearization of large-signal transconductance

3.4.3

Matching networks and circuit implementation

The optimum load impedance derived in equation 3.9 provides intuition but is a bit

simplistic. In addition to neglecting device output capacitance, there are several effects which are not included. For instance, device capacitances are voltage-dependent,

implying that under large-signal drive, the impedance seen will vary dynamically.

Further, actual power transistors are not unilateral due to internal feedback, implying that both output and input impedances affect output power and efficiency.

46

Large-signal models [42] provided by the foundry try to capture most of these effects

to enable computer-aided design. Under large-signal drive, active devices produce

power at the desired fundamental frequency and its harmonics. Given a specific active device model, bias condition and supply voltage, PA behavior can be described

as a function of source (gate) and load (drain) impedance vectors:

77PA

=

fl([ZL(w) ZL(2w) ...], [Zs(w) ZS(2w) ...

POUT = f2K[ZL (W) ZL (2w) ...], [Zs(w) Zs(2w) ...])

(3-14)

(3.15)

PA design optimization can be partially automated through large-signal load-pull

simulation. As shown in figure 3-9, the impedance tuners are controlled by an algorithm that searches for optimal impedance vectors which maximize either efficiency

or output power. Generally, the impedance vectors corresponding to maximum output power and efficiency lie close to each other. In the present work, the design is

optimized for efficiency.

GmZ

GrLoad

port

ZL

Source port

Zs

Figure 3-9: Load-pull setup

With load-pull based designs, it is common to specify impedance vectors up to

the third harmonic 3w. However, accurate control of harmonic impedances is more

appropriate for distributed designs and not always possible in lumped, integrated

designs such as the present one. Further, with lumped designs the efficiency enhancement resulting from optimized harmonic impedances is often negated by losses arising

47

from the additional passive components needed. Since the device capacitance tends

to rotate towards a short at higher frequencies, ZL(2w)/ZL(3w) and Zs(2w)/Zs(3w)

are set to 0 leaving ZL(w) and Zs(w) as the only degrees of freedom. Augmenting

equation 3.9 to include device capacitance, the theoretical Zpt(w) serves as a good

starting point:

Zopt (w) = Ro

.

jWCO,PA

(3.16)

Initially, the source impedance is set to Zo to determine ZL(w) with load-pull,

and then a source-pull is performed to find Zs(w). Since efficiency is more sensitive

to load impedance, the optimal ZL(w) is used, while a somewhat sub-optimal Zs(w)

is used in order to improve stability. The final load and source impedances used are

presented in table 3.2.

Impedance

Value

ZL (w)

Zo(0.57 + jl.33)

Zs(w)

Zo(0.66 + jO.36)

Table 3.2: PA impedances at fundamental frequency

The complete PA schematic is shown in figure 3-10, while the corresponding component values are listed in table 3.3. At the drain, the shunt-L series-C match provides

impedance matching from ZO to ZL(w), DC bias and RF signal coupling with only

two elements. A series-C shunt-L match is chosen for the gate as it performs the

transformation from Zo to Zs(w) while also a symmetrical split of the RF signal to

feed the two gates in phase for the dual-bias topology.

48

VDD

TXEN

KR3 VTRX

L1

M3

C2

VB1

M2

C2

VB2

Figure 3-10: PA schematic

Component

Value

M1 , M 2

180x2 pum

M3

80x4 pm

L,

1.22 nH

L2

1.25 nH

Ci, C2

2.20 pF

C3

0.33 pF

300 Q

R 1, R 2

2 KQ

R3_

Table 3.3: PA component values

49

..--VD (tO RXSW)

3.5

RX design

3.5.1

RX switch

Since the RX incident power is quite low the RX switch is not required to conduct a

lot of current. However, it must meet two other requirements:

1. In TX mode, isolate and protect the LNA from the high-power PA which is

transmitting.

2. In RX mode, provide sufficiently low insertion loss to not significantly degrade

the noise figure of the RX path.

The series-shunt configuration is the preferred switch topology to improve isolation

and power handling [43]. In general, GaN is an excellent technology to implement

high-voltage RF switches. The high breakdown voltage of GaN devices allows use

of just a single device in the series path, which reduces on resistance and therefore

insertion loss in the RX mode.

The RX switch schematic is shown in figure 3-11, with waveforms corresponding

to the TX mode, which represents the high voltage stress case. Recall that in this

modified frontend architecture (see figure 3-4(a)), the RX switch is directly connected

to the drain of the PA device denoted here by VD. As shown in figure 3-5, the

maximum RF voltage amplitude at VD in the TX mode is simply:

Vmax

=

(3.17)

VDD - VDSAT

The capacitor C1 can be assumed to be an ideal DC block for the present analysis.

The LNA input VLNA is grounded through M 2 , which is on. The voltage stress at VD

is shared equally in the divider formed by the gate-source/drain parasitic capacitors

Cp of M 1 , which is off. The control voltage VOFF should be chosen such that the RF

voltage stress does not accidentally turn on M 1 . Therefore, VOFF should satisfy:

VTH

> max(Vcp)

50

= VOFF + Vmax

2

(3.18)

RXEN (= VOFF)

VCP(-t

R1

Cp

+ CP

~ (0)

VD

VNA

C1

M2

VD ()R2

TX_EN (= VoN)

Figure 3-11: RX switch schematic showing TX mode waveforms

Where it should be noted that the threshold voltage VTH is negative in this depletionmode technology. Using the process parameters with the maximum expected VDD,

VOFF = -25 V is found to provide adequate margin for this design. In choosing the

switch device size, insertion loss trades off against isolation and area. The switch is

sized to keep loss under 1 dB.

3.5.2

Low noise amplifier (LNA)

The primary difference between the required LNA and most other implementations

is the need for a reactive input impedance ZLNA which forms the conjugate power

match with ZTX and the RX switch. In the RX mode, the RX switch is simply a

small series resistance RON, therefore the matching condition is:

ZRx(w) = Re(ZLNA(w)) + RON + jIm(ZLNA(w)) = ZTX(W)*

51

(3.19)

It is well known that inductively degenerated LNA's [44] are capable of synthesizing a reactive input impedance with independent control of real and imaginary parts.

Further, they provide good noise figure by providing some resonant voltage gain before the signal reaches gate-source junction of the active device. This topology is also

inherently narrowband, which suits the 802.11p application well. For the inductively

degenerated transconductor shown in figure 3-12, the input impedance Zin is given

as:

Zin = WTLs +j

wLs - WCg)

(3.20)

Depending on the technology and desired real part of Zin, the overall impedance

may be either capacitive or inductive. However, it is relatively simple to rotate the

impedance to the correct half of the smith chart by simply adding a compensating

reactance +Xc such that:

ZLNA =

±jXc +

WTLs + j

wLS -

(3.21)

Xc

F

ZLNA

Ls

ZIN

Figure 3-12: Transconductor with inductive degeneration [44]

Figure 3-13 shows the complete LNA schematic, while the corresponding component values are listed in table 3.4. The LNA active device is not downsized aggressively to maintain correlation with device models, which are not fitted to very small

geometries. For the input matching network, some co-optimization is performed with

the RX switch to improve performance. The output matching network performs an

upward impedance transformation similar to the PA in order to extract more gain

52

from the device, in addition to conveniently providing both DC bias and RF signal

coupling.

VDDLNA

L2

VRX

VLNA

C'1

M1B

R1

L3

VB3

Figure 3-13: LNA schematic

Component

M

Value

100x2

_

pm

L,

2.60 nH

L2

2.40 nH

L3

0.37 nH

C1

2.20 pF

C2

0.30 pF

R,

2 KQ

Table 3.4: LNA component values

53

-2

3.6

Physical design

A prototype based on the proposed architecture is designed in commercially accessible

GaN technology [39]. The die micrograph is shown in figure 3-14. Total die area is

only 2.0 mm x 1.2 mm. The area split between the TX and RX is about 50/50

owing to the large number of passives in the RX path. Spiral inductors and metalinsulator-metal capacitors are used to design all matching networks. Co-simulation

with foundry supplied device models and EM simulation-based models5 is used for

final verification of the design.

Package inductance is a major concern at 6 GHz. However, flip-chip packing is

not an option as the metallized die backside must make good thermal and electrical

connection to achieve specified performance.

As a compromise, a combination of

eutectic die attachment followed by wire bonding directly on board is selected. The

PCB is designed on a high dielectric constant, low-loss material (Rogers 3010).

5

for interconnect in the signal path and passive components

Figure 3-14: Die micrograph

54

Measurement results

3.7

Small-signal response

3.7.1

Figure 3-15(a) shows the small-signal response of the RF frontend in the TX mode,

with the RX port terminated. Input return loss (s11 ) is better than -20 dB, while

power gain (s2 1) is around 10 dB for the band of interest (5.850 - 5.925 GHz). Changing the port configuration and control voltages gives the small-signal response of the

RX mode, which is shown in figure 3-15(b). Again good alignment with the band of

better than -13 dB and power gain

interest is observed, with input return loss (s1)

(s2 1 ) around 8 dB. Noise figure is measured with a calibrated noise source, and is

found to be 3.7 - 4.0 dB in-band. TX/RX path isolation (not shown) is better than

-45 dB in band.