MOVEMENT TOWARD WELL WORKPLACES, COMMON CHARACTERISTICS

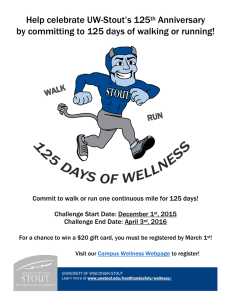

advertisement