I

advertisement

N

I

A

T HE RAP EU T 1

F 0 R

S TA T E

0C

C

0 M MU N I T Y

THE

0 F

U TAH

August 10, 1959

Submitted to the Faculty of the Architecture Department,

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

in partial fulfillment for

the Degree of

Master of Architecture

Pietro Belluschi, Dean

Dept. of Architecture and Planning

Imre Halass, Ass't. Prof.

Dept. of Architecture

Nei1 A stle

ABSTRACT OF 'JHESIS

In n correspondence with Dr. Charles E. Goshen, head of the Architectural Study Project of the American Psychiatric Association, the mental

health problem was emphatically evaluated as follows:

'The field of Psychiatry has been dominated, during the past

100 years, by major architectural achievements.

This has been

due to the fact that mental health, until recently, has been

looked upon as a problem which was subject to solution by means

of building institutions.

The results of the trends during the

past century have been that we are now saddled with 6ooooo

institutional beds which are designed in such a way as to make

rehabilitation virtually impossible.

big, too remote,

These hospitals are too

too poorly staffed, too poorly designed to

serve the function of rehabilitating the patient.

As a result,

few patients get out of these institutions, and even when they

do, it

is only after such prolonged periods of hospitalization

that they have lost their rehabilitative resources on the outside and over a third of them return to the hospital.

Today we have a much different concept of what constitutes good

psychiatric care than we did in the past, and for these new

concepts we need an entirely new architectural approach.'

Realizing the need for new concepts of mental health design, it has

been the object of this thesis to explore present trends and treatment

procedures and to derive from these a working concept of a therapeutic

- ,-- . -. --.-. . ... ..-

w

h9. .~

--

---- - ---

R

-11 I li-

community.

The basic assumptions made in arriving at a concept are

based on the interviews, correspondence and writings of some of the

leading authorities in the field.

Although many factors such as cost, availability of land, etc., are

very important, the prime objective of this project will be the rehabilitation of the mental patient.

The intent of this thesis project might be stated as follows:

To aid in the resocialization of mental patients through the creation

of an environment based on organized vitality and freedom.

The en-

vironment must turn outward to the public inasmuch as the complex

must become an active part of the community which it serves and the

patient must ultimately return to this community. On the other hand,

the environment must offer privacy and security.

A maximum number of

choices must be available to the patient in the form of activities and

social relationships in order that the patient might choose and develop

those social skills that are best adapted to his individual rehabilitation.

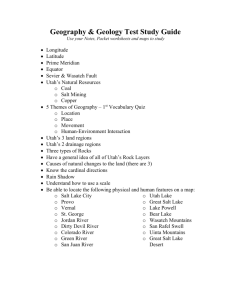

CONTENTS

Title Page

Abstract of Thesis

Page

'IILE OF

0ONTENTS... . ..

*.*.................

THE NEED

The Need for Therapeutic Comunity..........

Needs of the Patient........................

HISTORY

History of Mental Hospitals.................

History of Mental Hospitals in Utah.........

BASIC THEORY AND DESIGN CRITERI

Therapeutic Criteria....................

Hospital........................

Activities.............................

The Day

1

3

5

16

19

31

37

39

THE ROLE OF THE ARCHITECT

Visual

Order..............................

StZ.............................................

sIT.............................................

47

51

52

PROGRAM

Genra1............................

General Diagnosis and Outpatient Treatment..

Public Facilities ..........................

Staff Facilities.......*............. .......

55

58

59

59

Educational Facilities......................

Adjunct Treatment Facilities................

61

61

Indoor Activities.......... ........

........

Outdoor Activities.. ........................

Service Areas............-..-.......

62

BIBLIOGRAPHY........*.O....*................0.

63

6

THE NEED

Need For Therapeutic Community

In general, mental hospitals are misunderstood.

The large

mental hospital we know today is antiquated and obsolete.

Many

of these hospitals have patient populations in excess of 2,000

with some ranging (in size) up to 5,000.

Institutions are still

being built even though it has become impossible to staff them

and for that reason to make true hospitals out of them. Only

fifteen states have more than 50% of the total number of physicians

needed to staff their mental hospitals.

In the words of Harry 0.

Solomon, M.D., 'I do not see how any reasonably objective view of

our mental hospitals today can fail to conclude that they are

bankrupt beyond remedy.

I believe therefore, that our large mental

hospitals should be liquidated as rapidly as can be done in an

orderly and progressive fashion."

There are already many signs of self-liquidation.

In Massachusetts

for example, there has been a steady increase in the number of

patients in hospitals followed by a leveling off and an actual

decrease in the number of patients.

This trend is common to most

of the states including the state of Utah. Utah's State Mental

Hospital reached a peak patient population of 1,389 in 1955 and

then decreased to a present patient population of 1,143.

This

decrease is, in general, due to improved curative methods which

include shock and drug therapy as well as group psychotherapy.

The decrease in patient population has occurred with a corresponding

increase in the number of admissions, a decrease in death rate and

a population increase.

This suggests that if the present trend

continues even less bed space will be necessary.

We are now in a period of change. Psychiatric wards are being

opened in general hospitals; day hospitals and out-patient clinics

are being developed and services for patients staying at home are

being studied. More psychiatrists are becoming interested in

community endeavors that do not impose institutional environments

upon their practice.

There is an attitude of greater optimism

and a corresponding liberalization in the discharge of patients.

What of the less readily recoverable, however?

Their outlook

remains grim unless new ways are found to meet their needs.

They

will be sent to large mental hospitals where they will accumulate

in an atmosphere of gloom, despair, and deterioration.

We cannot

allow this to happen.

Mental hospitals should take into consideration the factors involved in community life.

The basic needs of mental patients are

no different than our own, however, they exhibit some characteristics that are different. For this reason, the mental patient does

call for certain features over and above those necessary for other

types of buildings.

The most pressing need in the state of Utah arises from the overpopulation of some 1,500 patients in a hospital that is in itself

obsolete and only adequate to house 900.

The state seems to be in a state of conflict between two major

4

philosophies.

On the one hand there are those who would favor a

continuation of the consolidated system with practically all of

the mental health facilities at Provo, Utah. On the other hand

there are those who favor the dispersed system consisting of a

state-wide hospitalization system.

This would relegate the state

hospital to a custodial function and the care of geriatric and

mentally deficient patients.

Under the first proposal, favored

by the State Hospital Administration and the Welfare Commission,

the State Hospital would continue to develop as a focal point of

mental health, care and treatment activities for the mental patients

of the state.

The second proposal (see charts pages 44-45) would involve a series

of out-patient clinics located at widespread points throughout the

state which would utilize existing facilities as much as possible

and would be staffed by either full time or part time psychiatric

teams.

These clinics would render out-patient treatment to those

who live at home.

The system would also include an intensive

treatment center where acute cases with possibility for recovery

would be given intensive treatment for a relatively short period

of time and then returned to their homes.

Under this philosophy,

which is adopted in this thesis, the state is in need of an intensive treatment unit for approximately 200 patients.

Needs of the Patient

The following are some of the principles of design as outlined

from the writings of Dr. Charles E. Goshen:

1.

The patient's viewpoint:

The mental patient is more self-centered than the average

person.

His rehabilitation demands that his attention be

directed outward, to other people and his physical environment.

The design must emphasize features which will draw

and hold his particular interest.

The design should not be

considered from an administrative or maintenance viewpoint.

2.

The patient's needst

Since the mental patient may spend many years of his life

hospitalized, it is necessary to provide him with the means

for satisfying the needs which other persons find in their

homes, communities and places of work. He must have privacy;

he must be able to express individuality; he must be able to

find entertainment for himself; he must socialize with others;

he must develop skills; and he must have contact with people

who can offer constructive leadership.

Since most of his

contact is limited to other patients, the design must be such

that he is allowed maximum opportunity for contact with people

from the outside.

3.

Design and personnel function:

Above all, the patient needs careful personal attention of skilled personnel.

The design and location of the hospital has a

good deal to do with who will work there.

It must, therefore,

take their needs into account.

In general, the patient's schedule should be geared to that of the

"outside"; in other words, there should be little deviation in what

the patient would experience if he were out in the community. Since

the complex will ideally become a part of the commnity with an

6

interchange of participants it is important that their daily

schedules coincide.

Thefollowing is an "Expression of Human Needs" as outlined from

an article by Walter E. Barton, M.D.:

'EUPRESSIONS OF HLt

NEIDS

"The organismts systematic requirements are known as its needs.

Like its other traits, they are an outcome of the interaction between inherited predisposition and environment,$ writes Dr. Sandor

Rado.

He continues:

investigative tool.

"Need is an explanatory concept rather than an

It has proved to be far more fruitful to des-

cribe the motive forces of behavior in terms of feelings, thoughts,

and impulses to act; and the mechanisms of behavior as organized

sequences of feelings, thoughts and action."

"We should distinguish between motivating pressures according to the

nature of the goals," says Dr. Thomas M. French.

"Some motivating

pressures have only negative goals, they are urges to get away from

something; to escape from pain or from the object of one's fear, to

put an end to the distressing physiological state of hunger.

These

states of unrest we call 'needs' or krives'; they are characterized

by painful subjective 'tension', which tends to seek discharge in

diffuse muscular activity, like the restless thrashing about of a

hungry infant.'

Definitions of the concept $need" consistently mention deficits or

absences and relate these to activity around which to restore an

unstable equilibrium. One rather formidable definition, by

7

Dr. Andras Angyal, will serve as a point of departure.

"Need is a biospheric* constellation in which the environmental

factor which is necessary to carry out the given function is

absent or insufficient."

1. NEED AS AN EXPRESSION OF VEGETATION AND REFLEX FUNCTION.

Need for oxygen requires no conscious effort on the part of

the person to satisfy.

Initiation of the fulfillment of the need

may be activated by the accumulation of carbon dioxide.

The organ-

ism breathes more deeply and takes in more oxygen.

2.

NEED AS EXPRESSED IN 00MPLEX STANDARD REACTIONS SUCH AS FOOD,

SEX, FATIGUE,

(a) FOOD:

EXCRETORY FUNCTION AND PAIN.

There is a biologic need for food, associated with a

physiological state of tension familiar to us as hunger.

When

one has taken a sufficient amount of food andfluid, the tension

disappears.

We are aware of a sense of well being when

appetite is satisfied.

But suppose a person is hungry and

has no money to buy food.

He may sleep and dream of food or

look at a magazine advertisement for food or may peer through

a restaurant window and watch the chef in his high white hat

toss the dough as he makes a pizza.

steal as his hunger increases.

He may be tempted to

Customary habits and restraints

block the action and the tension increases.

Situations of

unsatisfied tension can lead to personality disorganization.

(b) SEX%

is more complicated than hunger for food because it

is less specific in the kinds of activities which reduce

*The biosphere refers to the living space of an organism in

the earth, air and water.

tension.

The emotionally starved sailor ashore after a long

sea voyage may find his need for sexual gratification stimulated by a hip-swinging, curvacious blonde.

The expression

of need from that point on will depend upon many factors;

the sailor, the blonde, the circumstances and the complicated

conditioning process of the persons involved. But on the long

sea voyage what dreams did he have and what consolation did

he give himself, and what of the inclination to choose substitute objects, which in olden times was the peril of cabin

boys?

Sexual appetite is but one small aspect of the express-

ion of the need related to the complex reaction - sex.

(a) FATIGUE: After severe physical or exhausting emotional

situations, we may be overwhelmed with a sense of fatigue and

require rest and relaxation. Adequate satisfaction of the

need will vary widely with the individual and the situations

that produce fatigue.

Rabbits kept from sleep, but otherwise

well cared for, frequently die. In one experiment with a

volunteer human subject, who maintained a waking state for two

weeks, paranoid ideas emerged.

The experiment was discontinued.

(d) EXCRETORY FUNCTION: Mioturation and defecation result in

part from a reflex function, arising from the accumulation of

waste material.

Traumatic emotional experiences and great ten-

sion may alter the excretory pattern. There may be an urge to

defecate while waiting for an athletic competition to begin.

Fear may produce involuntary elimination. Related by the earliest demanding learning situation, toilet training, the

expression of need in the excretory sphere may be tied up with

the desire to be clean in person; a concern with personal

appearance; and neatness of clothing. Some will look upon

dirt as bad, contaminating and defiling.

In the fullness of

their opposition to demands upon them, others may use excretory products aggressively in ways more distressing than our

universal tendency to "toilet talk" in states of anger.

Others may, in certain social situations, retain excretia to

the point where tensions arise that directly influence behavior.

(e) PAIN: In a normal state, every individual desires to avoid

pain, irritants, and injury.

He strives to maintain physical

health and to void physical illness.

however, are also well known.

Distortions of need,

It sometimes becomes Necessary

to protect a patient from his own hostile impulses, or he may

attempt to injure others as a result of intolerable inner tension.

The subjective experience of pain is apparently absent

in some so that illness is not signalled by pain and disability.

5.

NEED AS EXPRESSED IN CHOICE FUNCTION, LIMITED BY THE PERSONAL

EXPERIENOE OF THE INDIVIDUAL, HIS PERSONAL SITUATION AND BY

THE CULTURE.

These are, in fact, more "psychological" needs, subject to a

wider range of individual variations than those previously listed.

(a) DRIVE FOR ACTION: There is a drive within us all to do

things, to make things

happen, sometimes just for the sake

of experiencing one's self as the cause of change.

Some who

experience too much failure and frustration in life seem to

settle for fantasy or imagined activity.

(b) THE DRIVE FOR SUPERIORITY: This, we speculate is part of

our heritage if we can generalize from 'pecking orders" in

hens, dominance orders in subhuman primates and even bunting

orders in the docile cow.

We have a need to compete success-

fully with others and, where the need is free to express itself

we do one thing well or one thing better than anyone else.

Some have a need to dominate others, to inflict their will

upon those who are less self-assertive.

(o)

THE DRIVE FOR ACQUISITION: People desire to have something

of their very own, just as there are collectors of territory

and shining object among birds.

The patient, if allowed, has

his own bed, his own place to the table, his own living space.

There is a desire to extend this ownership, to accumulate

property and to accumulate material things.

Patients in mental

hospitals have less opportunity to satisfy this need, and when

there is a limitation of owned space, they may carry a shopping bag stuffed with an amazing collection of old newspapers,

a crust of bread, a glass or a spoon.

(d) THE DRIVE FOR EXPLORATION ( OR COGNITIVE MASTERY): There

is a natural curiosity within all of us that is relected in

an eagerness to know about the world.

We want to know about

things. We seek knowledge for the sake of knowing and sometimes to satisfy self-expansive tendencies.

We desire an

opportunity for growth in knowledge, in understanding and in

opportunity.

Satisfaction of this need would avoid situations

that tend to create dependency and deprivation.

(e) THE DRIVE FOR INTEGRITY:

privacy.

sometimes.

around."

We resist intrusion into our

We need a place to which we can retreat and be alone

We don't like to be dominated or to be "pushed

The trend towards self-expansion, the will to power,

aggression, are manifestations of the person's individuality

and his need to be a person, set apart from all others.

4.

THE NEED EXPRESSED 7OWARD BEING A PART OF THINGS OR SOMETHING

LARGER THAN ONE'S SELF:

We have a need to be a part of a family, of a social group,

of a community, of a nation.

Our need is to share something with

others and to belong to a larger unit.

We wish to choose our own

associates and to have opportunities for social interchange. We

relate to our pastor or rabbi, to a particular church, to our own

faith, to our beliefs in our part of a larger spiritual world beyond

earthly things.

5.

NEED FOR RECOGNITION, APPROVAL, POSITIVE RESPONSE.

We wish to be appreciated and recognized by others, to have

a good reputation, to have a good social standing, to hold ourselves

in good esteem.

We have a desire to be loved. People usually

resent being a part of a regimented group. A nice balance is required to be one of the group and yet to be different and individual.

Most people dread to deviate too much from the group norm. We don't

like to be shorter, taller or fatter than our associates.

We do

not like to be dressed bizarrely. We want to keep to the fashion

yet to reflect our own individuality in that fashion. We do want

to be noticed; some desire this more than others. All of us have

a desire for attention.

We desire someone to talk to and a group

with which we can identify.

6.

NEEDS MAY BE EXPRESSED AS SUBSIDARY TENDENOIES.

(a) THE DRIVE FOR SECURITY: This need expresses a conservative

action to preserve the "status quo."

It has no primary goal

and is based on the anticipation that situations may arise

that would interfere with the satifactions ofadher needs.

The

drive for security may be expressed in the field of economics

or occupation, or reflect a need for love. The elderly person,

particularly, may resist change and prefer the situation to

which he is accustomed.

Some "play it safe' throughout life

while others are constatnly "sticking their neck out."

(b) THE DRIVE FOR ORIENTATION: All of us have a need to know

where we stand.

We need to know what the reasons were for

hospitalization, what the treatment plans are, who the doctor

is, what is expected of us, who are parents are, and what our

goals and ideas are.

A person needs a self-image that satisfies

"who and what I am".

We also need to know, "am I a male or

female, and what are my bodily characteristics?" - for us

normals, a silly question, perhaps, but a very serious problem

for some schizophrenic patients.

"Am I ill?

ful?

There are the questions,

If I am, how ill am I? Am I courageous or fear-

What can I remember of my past experiences?

place in a social group?

in the hospital?

I am well?

Where do I belong?

How long must I stay?

Why must I be

How can I tell when

What must I do to gain my release?

attitudes towards major life issues?

What is my

What are my

Do I regard life as

something to be treasured or a punishment for all my wrongdoings?

Do I regard death as a natural phenomenon that comes

to all individuals or is death a terrible punishing fate? What

kind of conception do I have of my own personal picture of the

HOWEVER, SOME PATIENTS FROM DREAD, PERHAPS, DENT THE REVELANCE

OF THESE QUESTIONS AND SO ASSERT THEIR UNREADINESS TO ACCEPT

In OTHER WORDS, THE DRIVE FOR ORIENTATION CAN BE

ORIENTATION.

DISTORTED OR ASKED BY ILLNESS.

13

life I live?"

(c) THE DRIVE FOR INTEGRATION: To assist a person toward selffulfillment, goals for himself and some perspective of life

are in order.

accomplish.

Goab represent the ideal of what one wants to

The child wants to be grown up.

personal accomplishment does the adult have?

What ideas of

There is a need

to do one's share in life or to live up to one's expectation

of one's self.

There is also the need not to disappoint the

others whose opinions we value.

The mental patient hopes that

he will once again regain his rightful place in the community

and may express his own aspiration toward the pursuit of happiness.

Returning now to the idea of "needs",

as a basic motivational

concept and the corollary of unfulfilled need as productive of

disorganized behavior and personalities, we may ask to what extent

can a therapeutic agency - like the mental hospital - restore the

balance of re-establishing in the patient an outgoing equilibrium?

The hospital can satisfy some needs as food, clothing and shelter.

Other needs are not easily met, such as the need for sex.

Some

other needs depend on the patient as the active person - needs

such as for approval or achievement.

The hospital can help, en-

courage, and provide a good "biosphere" but here we are "treating"

needs not meeting them.

Some optimal balance between meeting needs

and treating them is indicated."

REFERENCES

AMYAL, Andrus,-Foundations for a Science of Personality, Harvard

University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1941

BARTON, Walter E., M.D. - gpressions of Human Needs, Superintendent,

Boston State Hospital; Associate Prof. of Psychiatry, Boston

University School of Medicine.

GOSHEN, Charles E., M.D. - 'A Review of Psychiatric Architecture and

the Principles of Design', from Pyhiatric Architecture, American

Psychiatric Association, NW Washington, D.C.

OSMOND, Humphrey, M.D. - 'The Relationship Between Architect and

Psychiatrist', from Psychiatric Architecture, American Psychiatric

Ass'n. NW Washington, D.C.

SOLOMON, Harry C., M.D. - Exerpt from The American Journal of Pschiat,

Vol. 115, Number 1, July 1958.

SWENSON, Glen R., Utah State Bldg. Board 'Report on Mental Health',

Salt Lake City, Utah, 1958.

15

HISTORY

History of Mental Hospitals

In 1850 Thomas Kirkbride and his architect, Samuel Sloane, first

conceived of mental hospitals as a specialized field of architecture.

Kirkbride advocated moral treatemnt.

A period of 100 years passed

before the value of his treatment policy was realized.

In 1875

mental patients were given more freedom than in 1940.

During the

first quarter of the 20th century, there was a trend to build the

Kirkbride type of hospital but to detach it from the community.

It grew in size as it limited the patient's freedom.

Kirkbride felt

that hospitals should be limited to about 250 patients, or no more

than to make it possible for the superintendent to know everyone

in the hospital.

The hospitals built between the two world wars

were virtual warehouses.

Mental hospitals became similar in design

to prisons.

Insulin and electric shock treatments were introduced in the 1930's

and 1940's.

This type of physiological therapy still predominates

in private hospitals.

There has been a return recently to what is called moral treatmentnow called the therapeutic community or the open hospital.

The

essence of this type of treatment lies in allowing the patient to

maintain his dignity through constructive freedom.

Today then,

there exists a serious contradiction between the treatment program

and the existing hospital designs.

"All of our hospitals of the recent past have been designed for

16

efficient custodial care and isolation which is just the opposite

of contemporary treatment plans.3 according to Dr. Charles E.

Goshen of the American Psychiatric Association, 'We can learn very

little from existing hospital designs. Any study of past buildings

will only uncover many ways of not designing mental hospitals.'

The APA is crying for new ideas,as Dr. Humphry Osmond suggests

'Let us not make the same mistakes we made in the past, let us at

least make original mistakes."

Some of the factors that lead to the totally inadequate position

of our mental hospitals can be summed up by the list published by

the APA:

1.

The location of the hospital in a remote area--with a 'cordon

sanitaire" of grounds about it, to keep patients in and community

out.

2.

The construction of large, multi-story, unadorned brick build-

ings within extensive grounds; conspicuous features were window

screens or bars, 'sunporches" heavily grilled, and high fences.

3.

The housing of large numbers of patients in single buildings

and in large wards; by virtue of numbers alone the occupants were

deprived of any opportunity to express themselves as individuals.

4.

The use of obvious security devices, which not only depressed

the patients, but also had an adverse effect on staff and community

attitudes.

("this patient must be dangerous; he's in a barred room-

even the toilets are open to observation.")

5.

The use of uniformly drab furniture and colors, the almost

complete absence of accessories commonly recognized as being

expressions of individuality--pictures, draperies, floor coverings,

potted plants, a canary singing in a cage, and the absence of attention-getting and interest-holding design features such as picture

windows and so on.

6. The widespread use of building material designed primarily for

easy maintenance, such as tile walls, terrazzo floors, and so on.

7.

The absence of facilities where patients might store their

personal possessions, and the lack of opportunity for displaying

such personal items as pictures, family photographs and other

personal trivia.

8.

The use of uniform clothing for patients, somewhat resembling

prison garb.

9.

Mass feeding practices, with no choice of food, and the lack

of a full set of tableware.

10.

The mass transportation-"herding"-of patients from one place

to another.

11.

The lack of privacy for bathing and toilet facilities.

12.

The scarcity of means for the identification of time, place

arid persons--such as clocks, calendars, newspapers, photographs,

telephones, and other "normal* means of keeping in touch with reality.

13.

The absence of the traffic and activities common to ordinary

communities, such as shopping, holidays, meal getting, the "living"

activities of all kinds.

14.

The creation of construction features, such as a Usecure"

nursing station, which tend to limit personnel contact with patients.

(How often do you see a nurse "hiding" herself from patients by

busying herself with paper work in her isolated nursing station?)

15.

The use of materials and engineering features which allow

"institutional odors" to accumulate.

16.

The absence of objects which can become a matter of local

pride for individuals and groups of patients, such as pictures,

tropical fish tanks, plants and so on.

17.

The absence of facilities which would make it possible for a

patient to offer elementary hospitality- such as a snack, privacy,

conversation, etc.--to his visitors.

History of Mental Hospitalsin Utah

In 1880 the Utah Territorial Legislature made provision for what

was to become the present Utah State Mental Hospital.

The South

Wing of the 'Utah Territorial Insane Asylum" at Provo, Utah was

opened for reception of patients.

In 1927, the name was changed

to Utah State Hospital.

Since its establishment, the institution has experienced a more

or less steady growth. At the present time there are twenty-six

wards, 66,546 sq. ft. of bed space, 1303 beds and 16,491 sq. ft.

of day room space in conjunction with 34,746 sq. ft. of corridor

space.

The total admissions has increased steadily and now stands at over

630 per year. Likewise, the total number receiving care and treatment has increased on a yearly basis, until it now stands at 2667.

It is interesting to note that in spite of the rise in the rate of

admissions and the total receiving care and treatment, the average

patient population reached a peak of 1389 in the spring of 1955 and

has been decreasing since that time until it now stands at 1143.

The administration of the hospital attributes this decrease to

improvements in staff and curative methods which include shock and

drug therapy, and individual and group psychotherapy.

Four hospitals (two in Ogden and two in Salt Lake City) reported

a total of 1085 psychiatric admissions during the calendar year 1956.

Two more hospitals (both in Salt Lake) are planning to take psychiatric patients in the near future.

Compared to the 1085 psychiatric

admissions to general hospitals, the Utah State Hospital admitted

504 patients during the fiscal year, 1956-1957.

UMBER OF PSYCHIATRIC ADMISSIONS _

NAE OF HOSPITAL

UTH HOSPITALS.

d

COVERING YEAR

NUMBER OF ADMISSIONS

Dee Hospital

229

Jan. 1-Dec. 31, 1956

Salt Lake General Hospital

316

Jan. 1-Dec. 31, 1956

St. Benedict's Hospital

255

Jan. 1-Dec. 31, 1956

St. Mark's Hospital

285

Jan. 1-Dec. 31, 1956

Utah State Hospital

504

July 1956 - June 1957

TOTAL

18]

The state hospital at Provo has provisions for approximately 900

patients and yet it is presently housing about 1,143.

The buildings

are out-moded (and obsolete) and institutional in character.

Charts

on pages 22-29 perhaps best describe the present hospital situation

in Utah.

In general, the state is in a turmoil as to what policy to followwhether to continue with a consolidated system for which adequate

money has been appropriated or to switch to a decentralized plan

as favored by most psychiatrists.

ESTIMATED NUMBER OF PSYCHIATRIC PATIENTS ADMITTED TO GENERAL HOSPITALS

AND STATE HOSPITAL OF UTAH

BY COUNTY,

COUNTY

1. Beaver

2. Box Elder

3. Cache

Carbon

4.

5. Daggett

6. Davis

7. Duchesne

8. Emory

9.

Garfield

10. Grand

11.

Iron

12. Juab

13. Kane

14. Millard

15. Morgan

16. Piute

17. Rich

18. Salt Lake

19. San Juan

20. Sanpete

21. Sevier

Summit

22.

Tooele

23.

Uintah

24.

25. Utah

26. Wasatch

27. Washington

28. Wayne

29. Weber

STATE TOTAL

JAN. 1

ESTIMYA TED

NUMBER OF

ADMISSIONS

-

DEC.

31, 1956

*POPULATION

JAN. 1, 1957

4,500

21,500

35,000

21,500

PERCENT OF

TOTAL POPULATION

.54

2.59

4.16

2.59

.06

6.15

.90

.71

.42

.60

1.27

9

41

66

41

1

98

14

11

7

10

20

10

5

17

5

3

3

681

13

24

23

11

35

2Q

196

10

20

4

191

51,000

7,500

5,900

3,500

5,000

10,500

5,500

2,600

9,000

2,800

1,700

1,800

355,000

7,000

12,400

12,000

6,000

18,300

10,400

102,000

5,500

10,300

2,000

99,000

.31

1.09

34

.20

.22

42.78

-84

1.49

1.45

.72

2.21

1.27

12.29

*66

124

.24

11.93

1589

829,800

99.93

500

.66

EKISTING CONDITIONS

TOTAL AREA: 49,769 sq. ft.

ROOM AREAS

MEDICAL-SURGICAL BUILDING

UTAH STTE HOSPITAL

ADMINISTRATION:

Office

Office

Reception

175 sq. ft.

"

72

"

420

Conference

4r6

N

-

342

542

209

228

105

r00

=00

90

153

"

Office

Classroom

Office

Conference

Recording

Doctor

Nurses

Nurse

Nurse

Records

Nurse

Office

Nurse

Nurse

Nurse

Nurse

Nurse

"

N

4

"

"

N

"

*

166

"

404

228

N

404

58

58

58

58

TOTAL

a

"t

N

"

*

N

"

5,226 sq. ft.

10.5%

OPERA TORIES:

138 sq.

Exam

Exam

Exam

Exam

Autopsy

Histology

E.E.G.

Operator

EKG, BMR

Operating

Operating

Recovery

X-Ray

X-Ray

Cystoscopic

Exam

Exam

Exam

Ent

Surgical

Dental

Dental

Recovery

Ibid

Utah State Bldg.

138

138

N

'

132

a

340

153

"

"

96

N

68

100

"

"

382

"

382

126

"

"

388

N

336

"

225

99

99

94

N

213

279

"

94

N

"

N

N

94"

TOTAL

Board Report 1958

,

sq. ft.

8.4%

Page #2

LABORA TORIES:

Utility

Utility

Utility

Oxygen

Utility

170 sq. ft.

170

N

"

165

"

166

175

"

Lab

390

Preparation & Record

Film Viewing

Dark Room

Fracture

Splint Room

Plaster

225

90

189

210

41

31

66

Utility

Dark Room

85

Lab

48

Dark Room

Research Lab

TOTAL

"

"

"

"

0

"

"

'

'

33 "

340

2,594 sq. ft.

5.2%

sq. ft.

0.5%

23

PHA RMA CY:

BEDROOMS:

Wing

Wing

Wing

Wing

930 sq. ft.

930

"

"

2,376

'

2,460

B 2nd Floor

0 2nd Floor

B 1st Floor

C 1st Floor

TOTAL

7666

sq. ft.

SERVICE:

Lockers

Toilets

Toilets

Service

Janitor

Kitchen

Stretchers

Janitor

Dressing

Receiving

Washing & Sterilizing

Clean-up

Scrub-up

Service

Sub-Sterilizing

Shower & Bath

Toilets

743 sq. ft.

252

91

50

456

892

244

38

127

536

153

171

168

72

112

132

108

Shower & Bath

132

Toilets

Shower

108

149

"

*

"

0

"

N

"

'

"

"

0

0

"

"

N

"

"

"

"

13.4%

Page

#3

SERVICE, Continued

125 sq.

Toilets

Shower & Bath

Toilets

Janitor

TOTAL

ft.

N

128

105

"

l

5,123 sq. ft.

10.3%

STORAGE:

44 sq. ft.

'

44

"

44

"

44

'

127

'

81

'

150

'

96

N

88

3

30

"

709

27

"

Linen

Linen

Linen

Linen

Linen

Storage

Storage

Anesth.-storage

Storage

Storage

Supply

Storage

Storage

Storage

Linen & Clothing

Furniture storage

99

725

1,227

V

'

"

705

TOTAL

4,240 sq. ft.

8.5%

TOTAL

806 sq. ft.

"

806

"

1,405

"

1,543

770

"

755 x

a

3,801

"

4,419

2,8

17,041 sq. ft.

4.2%

CORRIDORS:

Wing

Wing

Wing

Wing

Wing

Wing

Wing

Wing

Wing

B

0

B

0

B

0

A

A

A

2nd floor

2nd floor

1st floor

1st floor

Ground floor

Ground floor

2nd floor

1st floor

Ground floor

MECHANICA L EQUIPMNT:

52 sq. ft.

Incinerator

Incinerator

Incinerator

Incinerator

Mech. Equi).

Mech. Equip.

Mech. Equip.

Mech. Equip.

M-ech. Equip.

52

TOTAL

"

52

40

750

800

'

74

'

"

"

"

210

"

2,441

4,471 sq. ft.

9-%

25

?ATIENT PoPULATION UTAH 3TATE HOSPITAL

BIENNIAL PERIODS 1948-PRESEIT

PERIoD

Total

12-1-47 to 11-30-48 - 1026

12-1-49 to 11-30-50 - 116

12-1-51 to 11-50-52 12-1-53 to 11-50-54 12-1-55 to 11-30-56 -

Under

o.&T.

1125

2151 - 91

1199

1174

1124

1174

1149

1195

1263

2310 -

97

Deaths

Discharges

77 168 - 272 338 610

79 176 -

12-1-57 to 11-30-58 -

2667 -

AVERAGE PA TENT ?OPULATION

54

54

55

1334

593

649

nd of Month

Biennial

1233

-

1285

-

1526

-

1341

1354

1361

1x48

13553

114

1284

1298

1315

1268

56

56

57

57

58

687

636

UTAH STATE HOSPITAL

1347

55

572

286

254

516

198 -

By Various Averages Based on Pts. in Hosp. at

6 Mo.

cal. yr.

Fiscal yr.

PERIOD

Periods

Jan-Dec.

July-June

Jan-June 48

1184

1195

July-Dec 48

1206

1217

Jan-June 49

125

1227

July-Dec 49

1243

1249

Jan-June 50

1254

1264

July-Dec 50

1273

1283

Jan-June 51

1294

1293

July-Dec 51

1292

1292

Jan-June 52

1292

1503

July-Dec 52

1315

1319

Jan-June 55

1527

1323

July-Dec 53

1332

1530

Jan-June

July-Dec

Jan-June

July-Dec

Jan-June

July-Dec

Jan-June

July-Dec

Jan-June

215

73 185 - 356

2323 -112

2325 -112

79 191 - 39

2450 -137 110 247 - 353

-

l-59

-

1299

PA TIENT POPULATION

1288

-

1291

1286

1502

UTAH STATE HOSPITAL

BIENIAL PERIODS 1948-?RESENT

Total

PERIOD

7-1-47/6-30-48

7-1-49/6-30--0

I

?irst Admissions

508 72o 628

354

289

643

7-1-51/6-30-52

574

7-1-53/6-30-54

7-1-55/6-30-56

7-1-57/6-50-38

351

384

257

262

317

631

615

701

Ibid.

833

Utah 3tate Bldg. Board Report 1958

Readmissions

74

119

101

902

88

139

175

144

116

150

213

294

245

208

218

272

Admissions

475

475

464 937

4o1 876

443

378 821

472

447 919

1105

PROVO UTAH STATE HOSPITAL STATISTICS

WARD

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

Ibid

SQ. FT. OF

BED SPACE

2579

2665

2592

2615

2592

2615

1796

1642

1932

1923

APA

RECOlMENDED

NO. OF BEDS

NO. OF

BEDS

264

264

2415

2404

2415

42

1076

49

44

4o

44

264

300

323

2898

2516

2549

58

559

3186

3508

46

47

5186

2346

2988

2346

47

46

34

43

34

CORRIDORS

49

50

52

51

46

FT.

OF

2404

2532

2404

45

38

26

25

27

27

41

36

A6

z186

5308

SQ-.

246

243

264

264

264

37

37

37

37

37

SQ. FT.

OF DAY RM.

SPACE

52

840

52

58

1096

830

60

1096

55

830

1096

51

52

830

1096

1096

64

2415

2404

978

937

16co

1600

800

727

800

727

800

52

830

36

53

62

1096

830

46

727

800

727

800

727

50

1096

8310

800

727

1305

16,491

54v746

46

3186

2522

3186

2884

41

66,546

953

55

Utah State Building Board Report 1958

27

COMPARISON FIGURES BETWEEN ADMISSIONS AND THE

AVERAGE PATIENT POPULATION AT UTAH STATE HOSPITAL,

PROVO, UTAH

750

1500

700

1450

650

1400

600

1350

550

1300

500

1250

450

1200

400

1150

350

1100

300

1050

250

1000

AVERAGE

PATIENT

POPULATION

ADMISSIONS

I

I

U

UK IAJ~

13

iDQC7

I

ADMINISTRATION

2

COTTAGE

3

COTTAGE

HARDY BLDG

4

5

DUNN BLDG

6

HYDE BLDG.

7

MEDICAL -SURGICAL

8

NURSES HOME

9

AMPHITHEATER

10 RECEIVING & TREATMENT

11 KITCHEN CENTER

12 GYMNASIUM

QUARTERS

13 RESIDENT TRAINEE

14 CHAPEL

I3

NO

TM

PRIOR ITY:

I

2

3

4

5

10

- 13

- 12

- Il

- 14

-

RECEIVING & TREATMENT

QUARTERS

RESIDENT

TRAINEE

GYMNASIUM

CENTER

KITCHEN

CHAPEL

NOTE:

FIRSTNUMBER = PRIORITY

SECOND NUMBER= BUILDING

NUMBER

o

so0to0

200

300

400

SYMBOLS:

PROJECTS

FEDERALLY

UNDER

DESIGN

FINANCED

OR CONSTRU/CTION

PROJECTS

(HHFA)

EXISTING

195 9

10

APPROPRIATION

YEAR

REQUEST

PROGRAM

FUTURE

U TA H

419

S T AT E

CAPI T OPL

MENTAL

BOUOI

L D IONPGOMT A R D

S ALT

LA KE

Cl TY

P R

APLO

S E D

M A SLT E R

HOS PI T A L

aUILDING

PLAANT"OE"A

P R OV 0

UTA H

JANUARY

1959

REFERENCES

KOHLER, Kivin J., Thesis, An Investigation of the Mental Hospital

Building2 Tn,

1954

PSYCHIATRIC ARCHITECTURE, American Psychiatric Association, 1700 Eighteenth Street, N.W., Washington, D. C.

50

BASIC THEORY AND DESIGN CRITERIA

Therapeutic Criteria

Anything that contributes to an institutional atmosphere or to

individual conformity is undesirable.

"The effects of institution-

alization on people in general and on mental patients in particular

are agreed to be a deterioration of morale and a suppression of

incentive to make constructive moves." says Charles E. Goshen, M.D.

Not all patients should be forced to feel and act alike and we

should in no way hamper the freedom of the psychiatric patient.

He should feel free to develop his own character.

In general,

human beings rebel against any influence that deprives them of

freedom and individualism and mental patients, although their actions might be different, react in the same way.

Patients need an environment that includes a wide variety of

activities.

As Dr. Kenneth E. Appel describes it, "Patients must

be able to be indoors or outdoors, to play with water, to write on

walls, to run and jump, to throw sticks and stones.

It is only

through such means that patients can express themselves in harmelss

ways."

The patient should be allowed to do almost anything as long

as he does not hurt himself or other human beings. We need, in

addition, more active energy outlets in the form of art expression

and with it self-realization.

Milieu therapy, which is the constant use of the patient's environ-.

ment for treatment, has become very important inasmuch as its only

supplement, psychoanalysis, suffers from a lack of adquate personnel.

A psychiatrist if he works very hard, might treat a total of 150

patients in a lifetime. With the shortage of psychiatrists we now

have, the failure to increase the enrollment of persons entering

medical schools, and the corresponding increase in population, it

is very likely that the situation might become even more acute.

Perhaps an even more important role in the patient's life is his

living experiences, activities and relationships.

A therapeutic community suggests, on the one hand, a place where

milieu therapy is employed, and on the other hand, an orientation

toward bridging the gap between hospitals as specialized institutions

and community life in general.

Anything that is strange gives rise to fear and anxiety.

In general,

our mental institutions are very different from our homes.

The in-

stitutional athletic field and amusement halls are very different

"The patient needs buildings

from those of the ordinary community.

that do not radiate crude force, restraint, herding, loss of control,

mystery, fear, danger, destructiveness, injury, death." says Dr.

Kenneth E. Appel.

Our present hospitals reinforce the public ideas

of mystery and danger in relation to mental patients.

The criminally

insane-those requiring some form of custody.- should not be located

near the intensive treatment units.

This in itself would alleviate

some of the public anxiety felt toward mental institutions.

Security has been the keynote in designs of the past.

This has been

the result of the community thinking it must have protection from

violence.

Dr. Goshen of the American Psychiatric Ass'n. is backed

by almost every contemporary authority and everyone interviewed for

this thesis, when he says, 'The fact is that only five percent of

32

mental patients are sufficiently destructive-and these only part of

the time-to require special measures of protection, and the best

way of curbing destructiveness is not necessarily through the use

of coercion, security, or other forms of restraint.'

Some authorities suggest a relaxed environment.

Others feel that

mental illness is similar to physical illness and that treatment

should be similar to surgical hospitals with emphasis on bed care.

Others think a remote location or monastic environment is ideal for

rehabilitation.

However, since the patient is required to return

to the community, it seems that the best solution would be one that

minimizes the break between the institution and the community.

The

patient should be kept as active as possible in fields that will

add to his social skills and better prepare him to return to society.

The patient we are concerned with spends up to six months in the

hospital and very little of this time is spent in bed.

datory that he has something to do.

both individual and group needs.

It is man-

Space should be supplied for

Emphasis should be placed on the

active part of the complex and not so much on the various wards.

The personnel should act as supervisors in the development of patient

activities which will help the patient establish social skills comparable to those of the larger society.

Although the social mores of different cultures vary greatly, most

socities distinguish between the normal and abnormal.

The line that

is drawn at this point is very sharp in contrast to the various

degrees of mental illness of which practically no one is free. And

yet, the mental patient has been cast out of the society which in

33

itself holds the only keys to rehabilitation.

When a person deviates in his actions from his fellow man he is

alienated to the point where he is deprived of his civil rights

by law.

"Alienation can happen quite apart from mental illness

when for any reason a person looses his ability to communicate with

society. Among the reasons for alienation are nationality, religion, criminal record, physical incapacities, political affiliation,

disease, etc.'

'Absolute power inevitably creates abuse", says Dr. Humphrey Osmond,

'and detention is a result of a high exertion of power.'

tion is a risk involved with all custodial relationships.

DegradaFor

this reason we must be very cautious in our use of custodial relationships especially as they involve persons who are not destructive.

'Persons then come to mental hospitals because they have been alienated from their friends and relatives and finally from their

community.1

Dr. Osmond goes on to say,

'The newly admitted person

is desocialized and one of the prime objectives of the mental

hospital is to repair it and strengthen his social relations.

At

present, our mental hospitals do not re-socialize, rather they

degrade and even brutalize.

Degradation can be avoided without

too much difficulty and we have known how to do this for 150 years.

However, a more subtle danger remains which is dis-culturation.

One can learn manners, values, etc., of a sub-society and never

really master the values of the greater society.

In other words,

a patient especially if he is institutionalized for a long period

of time, can adapt himself to a sub-society present in the hospital,

but never be able to handle himself in real life or in a greater

society. We must then maintain strong contact with the community.

Buildings which meet the psycho-social needs of our patients will

not by any means solve all of the problems of the mentally ill but

they will go some way to prevent the chance of degradation, reduce

dis-culturation and encourage re-socialization.... If a hospital is

not actively socializing it cannot help but be dis-culturing.'

Dr. Beaverly Mead of Salt Lake City suggests that the therapeutic

community of the future might be similar in principle to medical

treatment in the military during wartime.

Medical facilities are

almost immediately available on the front lines.

A man only slightly

wounded can be treated without changing environments and returned

to his duties as rapidly as possible.

If the wound is more serious,

the patient is taken to a station very near the front where he

might recuperate for a few days before being returned to the front.

If the wound is quite serious perhaps the patient must retreat to

another hospital further from the front and serving many small

sub-stations.

In this environment the patient might spend several

months before returning to the front.

And finally, if the wounds

are too great the patient is made as comfortable as possible away

from the battle area.

In the therapeutic development this might

take the form of (1)treatment in the home; (2)treatment in day

hospitals scattered throughout the area; (3)treatment in an intensive treatment hospital; and (4)custodial care.

The goals of the hospital can best be stated in the words of Dr.

Osmond:

"1.

To help people who have become alienated and expelled from a

35

community regain those skills which they have lost.

2.

To prevent any further loss of social skills remaining at the

time of admission to the hospital.

3.

To help patients acquire social skills which are lacking and

whose absence have reduced social effectiveness

and

so in-

creased the chance for alienation.

4.

To prevent the acquisition while in the hospitaJ of habits and

attitudes which unfit the patient for life in the larger

cummunity.2

Theoretically, the decentralized system suggested in this thesis

would alleviate many personnel problems.

The use of private hospitals

would make available psychiatrists primarily in private practice who

would probably never be interested in a full time hospital position.

These people might be interested in accepting responsibility for a

limited number of patients.

Most psychiatrists prefer the variegated

activities of private practice to the more uniform activities of

most state hospitals.

The decentralized plan would allow them to

continue the practice they have chosen and at the same time utilize

their skills for the care of state hospital patients.

The cost per patient would be higher for a decentralized plan for

that which exists in our state hospitals. With the new interest in

mental health and with the loosening up of insurance policies to

include mental disorders, we can expect more available money for

such a project.

The average cost per patient is now somewhere around

$6. per day as compared to $14. or $15. per day at surgical hospitals.

We should expect more allotments to be given to mental health above

$6. per day which is barely enough to let the patient exist.

In

addition there are many who are willing and are capable to pay much

more than they are asked by the state.

The Day

rospital

In the therapeutic development as outlined in the previous discuss.

ion, we have found the need for several "day hospitals" (as we shall

call them) scattered throughout the state to serve various communities

within the communities themself.

These will vary in size and design

according to the conditions of that particular area.

Such things

as site conditions, climatic conditions, the nearness to other medical facilities, the population served, etc., will influence all of

the designs independently and will make a proto-type day hospital

impractical.

This thesis is involved with all of the possible day hospitals, however, it will specifically deal with the design of the intensive

treatment portion of the overall plan which is fed by the various

day hospitals.

The intensive treatment hospital will most likely

include one of the day hospitals.

In such an outline the present

state hospital will be converted to the custodial function of caring

for the criminally insane and mental defectives (those who offer

little or no hope of recovery) and possibly some geriatric patients.

According to Dr. A. E. Moll, the day hospital may be considered

under completely different settings and any one may be employed

throughout the state according to the needs of that area.

1.

The Day Hospital as an integral component of the psychiatric

department of a general hospital:

In this case some of the personnel

responsible for day patients may also be responsible for the care

v

of patients in other areas of the hospital.

Some of the functions

may be shared with the inpatients.

The Day Hospital affiliated with a general hospital but situated

2.

in a separate building:

type described in

The difference between this type and the

1. is in the choice of personnel.

unit becomes more independent.

The entire

There is more chance for initiative

and spontaneity.

The Day Hospital as part of the community service of an Out

3.

Patient Department:

In this case, social services play a much larger

There is more communication between the day hospital and the

part.

community surrounding it.

4.

The Day Hospital affiliated with a mental hospital and situated

within its grounds:

ent aims.

In this case the hospital may vary with differ-

For example, the hospital might treat previous inpatients

who have been discharged from the mental hospital.

It may act as

the transition for commitment to the hospital, or it may care for

the psychiatric disorders within the community.

5.

The day hospital as a completely different treatment center.

*The day hospital may include all or some of the following:

a.

Individual or group psychotherapy.

b.

Therapy other than psychotherapy such as sub-coma, insulin,

E.C.T., narco-analysis, chemotherapy.

c. Occupational therapy.

d.

Educational diversional therapy such as the use of films,

discussion groups, etc.

*As outlined from article by Dr. A. E. Moll, 'The Nature of Day

Hospitals', from book, Psychiatric Architecture, A.P.A., 1959.

e.

Rehabilitation, vocational and training.

f. Therapy of the patient's family.

Day hospitals may fulfill different roles and the therapeutic management may emphasize one of many:

a. The hospital may be geared for patients reporting daily

such as from 8:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. (day patients),

b. Over and above day patients, it can also be geared to take

patients that spend only part of the day on the premises.

c. The Day Hospital premises may be used for treatment of

night patients, that is for patients who report daily after

working hours.*

The beds in the day hospital might be used for 24 hours of each day

by three different groups:

day patients for sub-coma or insulin

therapy in the morning, the O.P.D. patients for electric shock

treatments in the afternoon and the night patients from 6:00 p.m.

to 8:00 a.m. the following morning.

The day hospital is best located near public transportation and

patients' residences.

Urban or suburban settings are desired inas-

much as they should be readily accessable to community facilities

such as parks, civic centers, museums, shopping areas and others.

It should be inconspicious yet unhidden.

Activities

Persons who are well in addition to those who are hospitalized find

that activity is therapeutic.

A disturbed person is given the

*As outlined from article by Dr. A. E. Mll, 'The Nature of Day

Hospitals' from book, Psychiatric Architecture, A.P.A., 1939.

b

opportunity to find socially accepted ways of expressing himself

and of gaining self-confidence.

The patient can use activities as

a proving ground to seek out and apply himself to certain situations

that he will encounter in the greater society. He is given the

opportunity through activity to relate himself to himself and to

other human beings.

The patient should be made to feel normal in his surroundings.

should never feel that he is trapped into an activity.

He

There should

be a wide range of activities so that every individual might have

the opportunity to choose that to which he is best suited.

More than twenty individuals seldom act as a group.

It is advisable

then to design the activities to be used for several smaller groups.

Eight or ten is an ideal number. Isolation is undesirable but

privacy is essential.

The activity areas are the heart of the commnity and should be

located centrally if possible.

They should be readily accessible

to all of the patients.

Occupational therapy should include provisions for the usual crafts

such as wood working leather working, ceramics and weaving.

Vocational rehabilitation is becoming more and more important and

facilities should be provided to simulate vocational circumstances.

The patient should be placed in working conditions that test both

his innate ability and his capacity to perform during an eight hour

period.

In addition, provisions should be made to let patients work

within the community.

40

The design of the occupational therapy and the recreational therapy

areas should be such that they attract the patients and motivate

them to participate.

In addition tophysical activities there should also be a wide range

of social activities available such as theatres, kitchens, social

halls, barber shops, beauty shops, etc.

Some general recommendations for activities as set forth by the

American Psychiatric Association are as follows:

1.

All hospitals, special or general, should have facilities for

adequate recreation programs; the use of these facilities

should be promoted for the mental health of all patients,

even those who are confined for short periods of time.

2.

The detailed design and equipment of recreation facilities in

a hospital is a function in which professional recreation

leaders should participate jointly with administrators, architects, and other specialists.

5.

Maximum use should be made of community facilities, not only

to supplement institutional facilities, but also for the

therapeutic and public relations values of increasing contacts

with the community.

Conversely, the use of hospital facilities

should be offered to community groups whenever possible.

4.

Institutions and outpatient treatment centers for the mentally

ill should be encouraged to enter into agreements with schools,

parks, and other community agencies for the cooperative planning and joint use of their recreation facilities.

Such

cooperation would tend to lessen the problems resulting from

41

the isolation of the institution from the community.

5.

Recreation should be given strong consideration in planning

hospital landscapingto encourage a proper balance between

emphasis on the values of scenic beauty and on the values of

maximum and effective use of the areas for recreation. Where

large, undeveloped or reclaimed areas exist, they should be

incorporated in plans for recreation use.

6.

Indoor space allotted for activities should comprise at least

50 percent of the total patient space within the institution.

7.

The design of any recreation area should consider the flow of

traffic, safety hazards, durability of materials, ease of control, ease of maintanance, and ease of accessibility, as well

as aesthetic appearanoe.

8.

In planning recreation buildings or areas, careful attention

should be given to allowance for adequate parking space.

9.

Recreation buildings and athletic areas should be centrally

located with respect to the patients who are to use the areas.

10.

Outdoor areas require easily accessible service facilities,

which include toilet facilities, drinking water, and shower

and dressing rooms when necessary. Any area where patients

gather should provide the items mentioned above within a distance of 100 feet.

11.

Outdoor sports areas should be located sufficiently near

building units to permit patient spectatorship as well as

patient participation.

12.

All facilities should, where practical, be equipped with sufficient lighting to insure maximum use of the area.

15.

Adequate storage space for equipment is of paramount importance

42

to all activities.

14.

Wherever structurally feasible, ramps should be used in preference to steps.

15.

Careful attention should be given to acoustic problems in areas

where large groups gather.

16.

Fences should be used around areas only when they serve a specific recreation purpose rather than the confinement of patients.

Terraces or hedges may be used to confine activities to certain

areas.

17.

Sufficient benches should be provided for outside areas.

18.

Regardless of the size of the hospital, at least one bus and

one station wagon should be assigned for the full time use of

the recreation department.

19.

The specific equipment standards already established by other

agencies concerned with recreation should be adopted when, in

the opinion of the total therapeutic staff of the hospital or

the representative national societies, these standards are in

keeping with the therapeutic mission of the hospital.

20.

In order to keep equipment standards abreast of changes, an

agency should be established for testing and approving various

kinds of equipment for use with the mentally ill.

Such an

agency might be established by the cooperating agencies.

21.

An investigation should be made of those recreation facilities

needed for psychiatric wards in general hospitals and for such

special groups as geriatric patients.

*

Planning Facilities for Health, Physical Education and Recreation,

(Chicago: The Athletic Institute, 1956)

POSSIBLE STATE-WIDE HOSPITALIZATION SYSTEM FOR MENTAL ILLNESS IN UTAH

# Now available

##Participation

practically certain

##f Participation probable

#### Not presently available

1.

Utah State Hospital, Provo (#) including both

a. A Rehabilitation Hospital designed to care for

chronic, geriatric, custodial and long-term

rehabilitation patients.

b. An Intensive Treatment Center designed to provide

intensive treatment for patients received from

any county in the State but concentrating on

patients from Utah County.

2.

Dee Hospital, Ogden

(##)

3. St. Benedict's Hospital, Ogden

(46)

4.

(#4k)

L.D.S. Hospital, Salt Lake City

5. St. Mark's Hospital, Salt Lake City

(##4)

6.

University of Utah Medical Center, Salt Lake City

(###)

7.

Holy Cross Hospital, Salt Lake City

(#4&##)

8. Price City-County Hospital, Price

9.

Iron County Hospital, Cedar City

(###

10.

(Hospital in the planning stage), Richfield

(####)

11.

Dixie Memorial Hospital, St. George

(###)

12.

Uintah County Hospital, Vernal

(#-h*)

13.

Grand County Hospital, Moab

(##4)

14.

Logan L.D.S. Hospital, Logan

(###f)

44

POSSIBLE STATE-WIDE HOSP;TALIZATION SYSTEM FOR MENTAL ILLNESS

\N-HOSPITALS NOW GIVING

INTENSIVE PSYCHIATRIC

TREATMENT.

2-HOSPITALS SUGGESTED AS INTENSIVE PSYCHIATREC TREATMENT CENTERS.

[g.STATE HOSPITALS FOR BOTH LONG-TERM AND INTENSIVE TREATMENT.

50

OPEOPLE

}.ESTIMATED

OF

MILES

WITHIN

COULD

IHIS

HOMES.

THEIR AREA

BE

HOSPITILIZED FOR MENTAL

ILLNESS WITHIN

THESE

HOSPITAL ADMISSIONS FOR 1956 PER COUNTY.

BE HOSPITALIZED LOCALLY UNDER THE SUGGESTED

PEOPLE COULD

PLAN.

PREPARED BY DEPT OF PSYCHIATRY, UNIVERSITY OF UTAH, COLLEGE OF

FOR THE UTAH ASSOCIATION FOR MENTAL HEALTH.

MEDICINE

RE!FERENCES

APPEL, Kenneth E., M.D., 'Emotional Impacts', Design For Therapy;

Conference at Mayflower Hotel, Washington, D.C., 1952, American

Psychiatric Association.

BRILL, A. A., M.D., Pychoanalytic Pchiatry, Vintage Books, New York,

1956.

CAMERON, E. Owen, MD, 'The Development of the Day Hospital', selected

from 'Mental Hospital Design Clinic', _Pschiatric Architecture,

American Psychiatric Association, Washington, D.C., 1959.

GOSHEN, Charles E., 'Physical Facilities and Equipment', Psychiatric

Architecture, American Psychiatric Association, Washington, D.C.

GOSHEN, Charles E., M.D., 'A Review of Psychiatric Architecture and

the Principles of Design', Psychiatric Architecture, American

Psychiatric Association, Washington, D.C., 1959

MARTIN, Harold P., M.D., 'Architectural Planning for Activity Programs',

Psychiatric Architecture., American Psychiatric Association,

Washington, D.C., 1959.

MOLL, A. E., M.D., 'The Nature of Day Hospitals', Psychiatric Architecture

American Psychiatric Association, Washington, D.C., 1959.

OSMOND, Humphry, M.D., 'The History and Deciological Development of

Mental Hospitals', Psychiatric Architectur, American Psychiatric

Association, Washington, D.C., 1959.

OSMOND, Humphry, M.D., 'The Relationship Between Architect and Psychiatrist', Psychiatric Architecture, American Psychiatric Association,

Washington, D.C., 1959.

STANTON,- Alfred H. and SCHWARTZ, Morris S., Mental Hositals, Basic

Books, 1954.

SWENSON, Glen R., A.I.A., Director, Utah State Bldg., Board, Salt Lake

City, Utah, 'Report to State of Utah on Mental Health'.

INTERVIEWS

MEAD, Beaverly, M.D.,

SNYDER,

STANTON,

Benson R., M.D., Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Alfred, M.D., Director, McLean Hospital, Belmont, Massachusetts

HARRIS, Herbert I.,

Technology

SWENSON,

Salt Lake City, Utah

M.D., Psychiatrist, Massachusetts Institute of

Glen R., Salt Lake City, Utah

THE ROLE OF THE ARCHITECT--VISUAL ORDER

Man cannot tolerate chaos.

Out of the visual world, man must make order

and meaning so that he might live.

The mental patient is perhaps even

more acutely in need of a visual structuring of his entire environment.

He must be confronted with straight-forward, simply articulated spaces,

sounds and textures in order that he might easily relate himself to his

total environment.

The visual structure of the environment is important

along with the various functional requirements.

Man orders himself physically as well as mentally--the eye adapts to

light, sweat glands adjust to temperature, etc.

lated to a basic equilibrium.

The entire body is regu-

It is a dynamic equilibrium since bodies

and ideas are constantly changing.

There are, however, certain constant

identities that are retained by the person from the past that make up

the individual.

It is for this reason that the individual cannot isolate

himself from the world.

A psychological or a physical rigidity is un-

healthy for the individual, (since it has ceased to grow and man must

create new orders both physical and psychological to cope with the everchanging world.)

When someone creates a complete order, which is possible only in a work

of art, the degree of impact is much greater than usual since the degree

of order is much greater than that to which we are accustomed.

To obtain

a complete unity, one common denominator should be found in every aspect

of the surface.

Impulses such as color, form, scale, light, rhythm, etc.,

are always changing into infinite varities.

of possible impulses.

There are an infinite number

To relate yourself to another object, therefore,

you must find a common reference point and this can be in the form of

47

any one of the impulses mentioned above.

We respond more readily to

these common reference points because we are oriented by them.

We must

develop a continuity and heirarchy of spaces, rhythms, textures and colors

and we must find connecting links (analogies) that can orient all of the

parts to the whole.

Strong feelings are not enough for a work of art.

Artistic ability is

necessary to transform feelings into a visual form that can be enjoyed

by others.

Space is a quantity and space itself does not include all of ones experiences.

We are also concerned with quality of experience which is

necessary in a work of art.

Great architecture is not alone caused by a well formed building.

Great