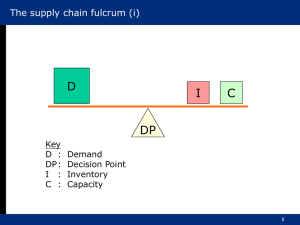

Reducing the Demand Forecast Error Due ... Computer Processor Industry

advertisement