COURSE PREPARATION ASSIGNMENTS: A STRATEGY FOR CREATING DISCUSSION-BASED COURSES*

advertisement

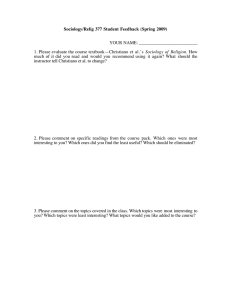

COURSE PREPARATION ASSIGNMENTS: A STRATEGY FOR CREATING DISCUSSION-BASED COURSES* crete strategies one such gests of a such course can time in guided of traditional the use rationale these material "Course on me allowing to discussions, foster the majority rather than student of class constantly David (CPA). assessment with engagement time coordinating, lecturing the This to article it to comparing reveals course at grounded the development by a discussion-based to create assignments course The the that this first exposure Assignment" describes courses, outcomes. several sug success about thinking so class activities engaging a discussion-based paper The attending for achieving Preparation assesses course and to substantively I propose This course. reading prior for discussion-based by spending leading students lack con often classes. larger a discussion-based exposure") to more the and lecture of "first The vehicle is in our particularly creating on is predicated CPAs, success, great for material the explains use and strategy discussion. course the so, (receiving be devoted lecturing, we like to get beyond for doing course material class a of us would many Although has the that a been course facilitating, and students. Yamane Wake Forest University THE DOMINANT PEDAGOGICALTREND today active over passive learning. emphasizes stu the research on college Summarizing Astin dent development, (1985) writes: learn by becoming "The theory...students to explain most of the em involved...seems gained over the years pirical knowledge influences on student about environmental Quite I mean What development.... ment involve by nor is neither mysterious student involvement simply, *I am grateful to Barbara Walvoord esoteric. refers to for teach ing me the methods described in this paper; to the Notre Dame Kaneb Center's Scholarship of Teaching and Learning Program for a grant to empirically assess this teaching strategy; to Abigail Roesch for research assistance; to all of the students in The Sociological Imagination during the 2003-2004 academic year for being a part of this quasi-experiment; and to the TS editor and reviewers for their constructive criti to the all correspondence address P.O. Box at Department of Sociology, Forest Winston-Salem, 7808, Wake University, NC 27109; e-mail: yamaned@wfu.edu. cism. Please author Editor's betical dendorf. note: order, The Jocelyn reviewers Hollander were, and in alpha Joan Mid the amount of physical and psychological energy that the student devotes to the aca demic experience" (pp. 133, 151). Simi Pascarella and Terenzini (1991) con larly, clude their review of the literature on stu dent learning by stating plainly: "The body of research on the impacts of the college The academic is extensive. experience [is that] the strongest general conclusion greater the student's involvement or engage ment in academic work or in the academic experience of college, the greater his or her level of knowledge acquisition and general (p. 616). This arti cognitive development" cle contributes to the literature on how to structure course work so as to realize these positive results. It proposes a strategy for away moving discussion-based from lecturing by courses in which creating students "Course complete Preparation Assign ments" (CPAs) as a prerequisite for in-class work. QUESTIONINGTHE LECTURECOURSE Although the exclusive use of lecturing for most courses, outmoded pedagogy Teaching Sociology, Vol. 34, 2006 (July:236-248) 236 is an lee COURSE PREPARATION ASSIGNMENTS_237 turing dominates the modern university as it In its time, this did the medieval university. sense. Before the dominance made perfect access students had limited printing press, to books and where they were available they were often too expensive for students to follows: "Now gentlemen, we have begun and finished and gone through this book as you know who have been in the class, for which we thank God and His Virgin Mother and all His saints. It is an ancient custom in this city that when a book is finished mass faculty had to read purchase. Consequently as a to books them precondition of analysis. to (1992), the dictation Gieysztor According was common more in central of texts should be sung to the Holy Ghost, and it is a good custom and hence should be ob served" (Haskins 1923:60). Things could not be more different today. Ready access to textual material means stu Europe where the pecia system for copying texts did not prevail, but "even in Paris, students asked their teachers to dictate the courses, for financial reasons" (p. 129). a representative Haskins (1923) gives picture of this system, citing jurist Odofredus's description: Concerning themethod of teaching the follow and modern own master, I shall observe: First, which method I shall I pro of each title before you summaries to the text; second, I shall give you as a statement as I can of the clear and explicit give ceed purport of each law [included in the title]; I shall third read text with the a view to cor recting it; fourth, I shall briefly repeat the contents ent of the law; contradictions, of ples [to be law and sage]... any fifth, I shall any adding extracted or distinctions solve appar general princi from the pas and use subtle ful problems (quaestiones) arising out of the law with their Providence as solutions, shall enable me. far as the Divine (P. 58) the Rait summarizes (1918) Similarly, practice at Vienna: "Ordinary lectures were delivered 'solimniter' and involved a slow and methodical analysis of the book. The statutes of Vienna prescribe that no master shall read more than one chapter of the text vel etiam quaestione ex 'ante quaestionem 140). So time intensive was it pedita'"1^. to work through texts in this way that com pletion of a book in lecture was a cause for celebration. Odofredus closed his course in the typical university is by the lecture method (Smith 1990:210). There has been "no general appreciation of the fact that the printing press [has] been invented in the years since the rise of the Medieval uni struction the Bolognese was ing order kept by ancient and especially doctors by my to dictate in dents do not need professors can so it down formation copy they (McKeachie 1999)2, and yet one estimate suggests some 80 to 90 percent of all in as (Edwin Slosson, quoted in Smith versity" are mired in the instruc 1990:214). We tional methods of the 12th century. Not some only is lecturing inefficient, however; as well. For exam question its effectiveness com ple, research conducted by Walvoord paring students' class notes to their profes sor's lecture notes finds they bear little re semblance to each other (personal commu see Walvoord and McCarthy nication; 1991). The widespread of informa availability tion frees faculty to employ other pedago uni students in the medieval gies. Unlike 2Indeed, faculty today could easily distribute their forfeit or even when the investigation is at hand." their raison directly or the web-and to realize d'etre by photo some do. that they would if they "gave away" lectures, all of the same type, and on a few set books, itwas probably desirable that there should not be opportunities of possessing Thanks to Dave Johnson and Boaz Roth for help such with 1918:142). the translation. to students their lecture notes in this way to students. This was apparently the case already in themedieval university: "Were [Parisianmasters] to dictate lectures or to speak so fast that their pupils could not commit theirwords towriting? From the standpoint of teachers who delivered fre quent ^he Latin phrase is: "before the investigation notes lecture electronic mail, copy, seem But most faculty copies of a professor's lectures" (Rait 238 versity who, lacking printed materials, were truly like "empty slates," students today can be expected to play a more active role in the learning process. To foster student involve ment we must transform classes from the traditional model based on lectures to an interactive model ing, discussing, based on thinking, writ and problem-solving. THE PROBLEM AND SOLUTION: PREPARATION FOR DISCUSSION to McKeachie (1999), if we are in "retention of information after the end of a course, measures of transfer of to new situations, or measures knowledge of problem solving, thinking, or attitude or motivation for further learning" change, According interested then we should consider research in which "the results show differences favoring dis cussion methods over lecture" (p. 67). Rec is one ognizing the superiority of discussion a strategy for thing; developing practical replacing lecturing with a discussion-based is quite another. Students and pedagogy both resist discussion in part because faculty I ask, stu it is often done poorly. When that their negative discussion far their positive outnumber experiences ones. Prior research has found unstructured than lecturing in discussion may be worse dents report terms of substantive engagement and cogni tive development (Gamoran and Nystrand I say "discussion" here, when 1991). Thus, I include by ellipses "guided" or "struc tured." Indeed, the entire purpose of this strategy is to avoid the pitfalls of unreflec tive use of discussion in class. Fortunately, we now have more and bet ter ideas for discussion into incorporating and than ever (e.g., Brookfield Preskill Beck, and Heyl 1999; McKinney, 2000). As I see it, the key is for students to come to class every day prepared to actively (Walvoord and engage the course materials Pool 1998). This means they must have read and thought about the course material classrooms before sure," page class. To achieve this "first expo I create and post to my course web various "Course Preparation Assign TEACHING SOCIOLOGY (CPAs) to be completed for nearly every class meeting.3 These CPAs ask the students to read and think about a particular chapter or part of the textbook and then to ments" a written response to a question or the problem assignment sets up. Each CPA has the same basic structure: (1) an intro ductory statement, (2) an objective for the informa (3) some background assignment, produce to the topic (if appropriate or and (4) the writing assignment necessary), itself. I have included as an appendix one of the CPAs I have used successfully in the to discuss racial past inequality.4 tion relevant The reading, thinking, and writing the students do to complete the CPA prior to class provide a solid foundation for high level engagement with the course material. I do not have to spend time lecturing about the topic because they have already had a first exposure to the material. During class, we move straight into discussion of the ma terial, often in groups of three or four stu as a class. Dis dents first, then collectively in small groups first cussing the material resources and con students additional gives fidence for the large group discussion. In the case of the CPA given in the ap pendix, I begin class by having the students work for 10 minutes in small groups. The to is have them goal bring their individual answers to the assignment together into a more To this whole. better, comprehensive a I to create ask them end, path diagram, with the dependent variable being the differ ence in family income between black and white families given in the assignment and the independent variables being their hy for the inequality. pothesized explanations In smaller classes, Imay give the students a to draw their dia transparency on which 3Novak et al.'s (1999) "Just-in-Time Teach ing" (JiTT) initiative provides a model of active learning that is very similar to the one I propose here, and has been usefully adapted to introduc tory sociology by Howard (2004). Supplementary CPAs are available on the Other than the Teaching Sociology website. CPA that appears in the appendix, each specific example I give in this article can be found there. COURSE PREPARATION ASSIGNMENTS to be projected for the class. But I typically just ask one student in each group to take responsibility for drawing the dia on paper and recording the names of gram the group members (to create some sense of gram accountability). these During 239 (e.g., Why layer of explanatory variables are a smaller percentage of blacks than are whites black college graduates? Why children more likely to live in single-parent, female-headed homes that white children?), more and by taking racial discrimination I small group discussions, circulate through the class, sometimes just sometimes en listening to the discussions, couraging the students to broaden or deepen their ideas, sometimes answering questions for them. In most cases, knowing they will to the class have to report their findings creates pressure on the students to do the seriously. After another 10minutes of small group work, we repeat the initial discus sion. By the end of the class, we have worked actively and collectively to create a seriously. Still, as I circulate I keep my eyes and ears open for groups that are not "on-task." This happens most fre the next CPA, which asks the students to come up with public policies that will re dress the many causes of racial inequality we have just identified. work others, friends, significant quently when and/or roommates constitute groups (which can happen often given student seating pat terns). As I note in an earlier article on col laborative learning groups (Yamane 1996), students often have bad experiences in groups they form themselves. One semester a prob when I sensed this was becoming lem, I randomly assigned students to discus sion groups for the balance of the semester. That solved the problem. When we get back together as a class, I ask each group to report one of their find ings; with this information, I begin to create a large path diagram on the chalkboard or a transparency. Inevitably, some of what the students report will be too simplistic, par tially correct, or entirely wrong. Rather than just saying so, I ask other students to suggest elaborations or corrections. Or, if I I will ask suspect a student is free-riding, that person to elaborate or correct the find ing. Getting the initial path diagram on the board usually takes at least 20 minutes. In this initial path diagram will my experience, have two flaws: (1) it will be too elemen tary and (2) it will not fully consider the role of racial discrimination. Indeed, both of these flaws are reflected in the students' tendency to reduce racial inequality to class inequality. So, I ask the students to get back together in their groups to render their path diagrams more complex by adding a second very comprehensive diagram explaining racial inequality in family income. This diagram, which I reproduce after class and email to the students, creates the basis for I use this particular example in part be cause it works so well. In a 75-minute class, 20 minutes are spent in small group 45 minutes in large group dis discussion, in transitions. Of cussion, and 10 minutes course, over an entire semester, we do not spend 100 percent of class time in discus sion. As I report below, I still spend about one-quarter of class time lecturing. But I find that my lecturing is qualitatively differ ent. Most importantly, I lecture in shorter segments, typically just setting the stage for or summarizing a discussion. For example, I may need to introduce a discussion by adding some ideas not found in the text book. As a prelude to our discussion of theoretical perspectives, I lecture for about 10 minutes on what theory is because the textbook does not do as good a job as I would like. I also conclude that class with a 10-minute summary of theories as "ways of seeing" because using sociological theory is so foreign to most students. Despite the clear limitations of lecturing as a general approach to teaching, these are some of the things lectures are "good for" (McKeachie 1999:67). To keep the class from getting stale, I attempt to vary the format of our discus sions from time to time. For example, in the discussion of public policies to redress racial inequality, I ask each small group to 240_TEACHING send one person to the front of the class to act as a commissioner of the U.S. Commis sion on Civil Rights and present their public policy solution to the class. The class then committee plays the role of a congressional In our discus interrogating their proposals. sion of theory, I divide the class into thirds and have each group represent one of three theoretical perspectives covered in the text is most in a debate over which perspective useful. Constructing ments Course Assign Preparation the objective is par CPAs, One of the reasons stu important. In constructing ticularly in class is because dents dislike discussion see not often do "the point." Of they can be a discussions course, open-ended even in if themselves, they lack a good I But sympathize clearly defined "point." with students' frustrations because I too am of spending much of the two to three we get to spend together in class each in non-directed activities. Thus, hav clearly stated objective for the CPA is essential, and that objective needs to carry wary hours week ing a over that follows. into the class discussion the objective needs to go be yond simply requiring the learning of cer tain content. For example, the objective of an exercise on identity formation might be to gain a better understanding of socializa tion by describing and analyzing the process by which religious identity isformed in vari ous institutions, schools, including family, If the peer groups, and the mass media. Furthermore, go beyond objectives learning the discussions to simply a recitation content requiring more than will be test the students' knowledge. itself must be the assignment Similarly, the assign carefully constructed. Typically, ment has two components: exposure to and In this class, engagement with the material. is almost always reading the the exposure textbook. It could be reading a newspaper or magazine, or using a source in the li be to do some observation or It could brary. experimentation-for example, the classic SOCIOLOGY In a textbook instruc "folkway violation." tor's manual I edited, I suggest a number of exercises wherein students are asked to visit and analyze websites (Yamane 2002). These could be adapted for use in CPAs. Of course, the number and type of questions asked would need to be adjusted to meet the needs of the particular situation. In terms of the questions I ask students in the assignment section of the CPAs, it is vital that at least some of them are authentic to Nystrand and Ga questions. According moran authentic (1991), questions have no students to answer, allowing pre-specified offer opinions, points of view, or informa tion that the teacher did not previously know. An authentic question has an indeter minate number of "right" or acceptable answers. questions promote sub in the exercise, and engagement a for foundation in-class stronger provide than a series of discussion inauthentic which often end up as ("test") questions, Authentic stantive dead ends in discussions. Like any other strategy, developing involves some trial-and-error. For CPAs example, to demonstrate that the "official poverty set line" by the U.S. government underesti mates poverty, I asked the students in a CPA to (1) make a list of all the goods and services your family would need to function at a minimum subsistence level, (2) estimate the minimum monthly cost of each of them, and (3) add up your monthly estimates and multiply by 12 to determine the annual total necessary to live at a subsistence level. The of this failed because the in my class had no idea year-olds to what goods and services are necessary or retro In cost. how much survive they spect, the underlying problem was that this in-class discussion 18-20 by assignment was not primarily motivated an authentic question. I had only planned for the students to reach one "right" answer in the discussion: that the official poverty line underestimates poverty. Because good CPAs are based on authen instructors who want to use tic questions, courses them to develop discussion-based need to be able to tolerate some uncertainty. COURSEPREPARATIONASSIGNMENTS 241 I set up has a specific it and certain ground learning objective a genuine seeks to cover, but ultimately cannot be fully controlled from discussion a discussion-based course I al In above. to that remain open the possibility ways lead me down unexpected students will Each discussion paths. That / may them in the process this design. learn something from is an inherent benefit of Grading Course Preparation Assignments I require students to bring printed copies of their assignments with them to class. If they do not attend class, they do not get credit for the assignment. This reinforces the rela and discus tionship between preparation students to attend class, sion, encourages and gives them a tangible point of reference Some instruc during the class discussions. tors might consider modifying this by " " the adopting Just-in-Time-Teaching on is predicated (JiTT) approach, which students submitting "WarmUps" to the in structor electronically before class so that the instructor can tailor the class to what is revealed by the assignments (Novak et al. 1999). Instructors doing so must keep in mind the additional time and resource com mitment required by JiTT (see Howard 2004). I grade the CPAs on a credit/no credit basis. Because closely grading CPAs for class be exhausting even in a would every I simply try to en class, moderately large sure that the students have made some seri ous effort to complete I the assignments. as an "serious effort" operationalize fully If they have done swering every question. that, I give them credit. In smaller classes, I glance at every written assignment turned in I before giving credit. In larger classes, a evaluate of the randomly sample assign so students know they are taking a chance that they will get caught if they try to submit less than adequate work. How to sample cannot be es many assignments tablished a priori. An instructor considering this strategy has to determine for herself how much time she has to read assignments ments she and how big a sample of assignments needs to look at given her personal and in stitutional circumstances. I find CPAs When that I deem inade a written warning I the students quate, give to ask and them rewrite the assignment be fore I deduct credit. I have found that stu dents at my university generally attempt to the assignment in some serious complete fashion even without a warning, but defi nitely after they are issued a warning and have to rewrite an assignment. For exam ple, in the spring of 2000, I had 60 students do 18 CPAs. Of the completed assignments, I had to write only five students one time each to encourage them to do a better job the CPAs. Spot checks of their completing work after the warning showed their level of engagement with the assignments had to an acceptable level. (Note: improved Faculty at other institutions may need to issue more warnings and deduct more credit than I have had to.) ASSESSMENT In 2003-2004, I undertook a systematic as sessment of the benefits of a discussion as based course organized around CPAs, a to traditional in lecture course, compared terms of four desired outcomes: (1) getting (2) creat beyond information transmission, a in democratic culture the classroom, ing (3) fostering student engagement with the course material, students and (4) helping learn more of the informational content of the course. (An assessment of the extent to which the lecture and discussion classes of the basic the three satisfy objectives course is available on the Teaching Sociol ogy website.) To establish a baseline for comparison, in I taught introduction to the fall of 2003, as a traditional lecture course. sociology The vast majority of class time (80%) was dedicated to my lecturing. When discussion did break out in class (10% of class time), it was usually unintentional. In the spring of I to introduction 2004, taught sociology as a course. Over the course of discussion-based 242 the semester, I spent 26 percent of class time lecturing to the students. By contrast, students spent nearly 60 percent of class time in small or large group discussion. (In both courses, administration or other activi ties not directly related to the course materi als took up the remainder of the time.) Both semesters the course was offered under the same number and description, assigned the same textbook, and restricted enrollment to 70 second-year students. The key difference between the two semesters was that the dis course was organized around cussion-based the CPAs. The question is whether the dis course better realized the cussion-based course. I outcomes than the lecture desired assessed the desired outcomes in three First, I used certain items from the official Teacher and Course university's Evaluation (TCE) data for the course. Sec ond, I used a number of items from a sur to get at the par vey I specially designed ticular outcomes to which I aspire. Third, I used exam scores to measure one aspect of ways. student learning.5 Getting Beyond Information Transmission A general objective of the discussion-based course transmission and is to downplay memorization of factual information and to emphasize higher order thinking skills such as synthesis of ideas and evaluation of argu ments. Table 1 compares the two courses on the extent to which they emphasized these different mental activities. students reported By significant margins, course emphasized that the discussion-based evaluation and synthesis more than the lec ture course, and that the lecture course em phasized "memorizing facts or procedures" in the same repeated "pretty much than the discussion-based form" more to be course. 5When ples t-tests significant courses. appropriate, to determine difference For t-statistics I used whether exists where sam independent a statistically between Leverne's the two test at the .05 is significant of variances for equality are assumed; or below, variances level equal are assumed. variances otherwise, unequal TEACHING SOCIOLOGY I also asked students about their level of statement: the following agreement with The instructor stimulated independent think less than half of the students ing. Whereas in the lecture course (43.5%) strongly agreed with this statement, fully 75 percent course of the students in the discussion-base I ex This is what strongly agreed. exactly pected and hoped for. Culture and Sense Creating a Democratic of Ownership and Preskill As Brookfield (1999) argue, courses hold out the prom discussion-based or ise not only of realizing course-specific skill-based but also of learning objectives, fostering respectful engagement of students with one another and with the professor, and in doing so creating a model for democ ratic civil society. One way I think about this issue is in terms of concretely of the course. Lecturing is "ownership" authoritarian in the sense of having a single individual as the source and summit of knowledge and everyone else as subordinate to that individual. This situation relieves the students of any sense of responsibility for the success of the course. A "good course" becomes one in which the professor lectures well and a "bad course" one in which the lectures poorly. But a democratic professor culture is one in which individuals feel some responsibility for the common good. I aspire to foster in students a sense that they share responsibility for the success of the course-our political community writ small. 2 and 3 display various measures of the democratic culture and sense of own ership of the course from the students' per Tables spective. Table 2 reveals that almost half of the students in the lecture course (48.6%) responded that responsibility for class being successful on a daily basis was primarily the the students' or evenly divided between and the students. These are re numbers for a course in which I spectable made no specific effort to cultivate this. But they pale in comparison to the 85.3 percent course of students in the discussion-based professor who responded that responsibility for sue 243 COURSE PREPARATION ASSIGNMENTS Activities 1.Mental Table To what extent has this Emphasis course em- phasized the following activities? (A) Memorizing so you can much facts repeat in the same (B) Synthesizing or procedures them pretty form and organizing or experi information, into new and more complex and relationships interpretations ideas, ences (C) Evaluating ments, of Course Level Lecture of % Very Little Mean (Std. Dev.) % Very Much Mean (Std. Dev.) %Very Much of (Std. Dev.) their aResponse Categories/Coding: 5 = Not at All conclu Mean Discussion Course Course Emphasis information, argu or methods and determin ing the soundness sions *p<.001 hy Type 11.4 35.3 2.57a 3.09a (.94) (.89) 27.1 44.1 2.03a 1.65a (.80) (.66) 21.4 41.2 2.36a (.93) 1 = Very Much, 2 = Quite a Bit, 3 1.81a .3.31* 3.06** 3.68* (.82) = Some, 4 Very Little, **p<.01 is primarily the students' or evenly divided. Only 14.7 percent of students in course felt the respon the discussion-based was com sibility primarily the professor's, cess pared to 51.4 percent in the lecture course. Table 3 shows that this sense of responsi bility was not limited to "students" corpo students in the discussion rately; many based course felt their contributions as indi viduals were important to the class as a whole. Table 3 also demonstrates that the discus in sion-based course was more successful bringing multiple voices into the public fo rum of the classroom. More students in the course than in the lecture discussion-based course agreed or strongly agreed that hear ing the views and experiences of other stu dents was an important part of the class and something (86.7% vs. 52.9%) they I have benefited from (88.2% vs. 55.7%). heard colleagues complain that students do not want to listen to their peers: these re sults suggest that this may be due to the student contributions fit into the way course. Perhaps instructors are allowing too much aimless unstructured, rumination, which students rightly feel is a waste of their time. Finally, Table 3 shows that students in course saw me as more the discussion-based interested in their points of view and more receptive to their questions. No matter how many times "Sage on the Stage" lecturers tell students they welcome and questions their actions speak louder than comments, their words. By actually modeling that re it central to the very ceptivity and making I was of the class sessions, organization able to realize these goals more in the dis course cussion-based than in the lecture course. By fostering a democratic culture based on mutual respect and a sense of stu course dent ownership, the discussion-based truly became more of a collegium than any lecture course I have taught. Fostering Student Engagement I have previously mentioned Astin's over arching conclusion "that "students learn by becoming involved. By involvement, Astin (1985) means simply "physical and psycho logical energy that the student devotes to the academic experience" (p. 151). The time a student spends on a course is a rough but appropriate of in operationalization volvement or engagement. Table 4 reports two different measures of student time spent, one from my own course evaluation and one from the univer 244 TEACHING SOCIOLOGY Table 2. Students' Sense of Responsibility Responsibility for class Lecture being successful on a daily basis was: Course (A) Primarily the professor's _ for Class by Type of Course Discussion Level of Course Pearson %2 Significance 51.4% 14.7% (B) Primarily the students' 2.9% 10.3% 21.80 .000 (df=2) (C) Evenly divided between the professor and 45.7% 75.0% the students I asked stu sity's standardized evaluation. dents how many hours per week, on aver age, they spent on my class. Students in the I asked students to respond to the statement, / looked forward to attending class, two thirds (66.2%) of the students in the discus course reported spending discussion-based 5.3 hours per week compared to 3.8 hours per week for students in the lecture course. Put otherwise, the students in the discus course spent 40 percent more sion-based time per week on my class overall, and over sion-based as much time outside of class (factoring out the 2.5 hours per week most students spent in class). Although 5.3 hours is less than most faculty would per week to a three students would devote hope data credit-hour the comparative course, here that the discussion-based suggest course does foster more engagement with the class than the lecture course. Unfortu nately, I do not have more detailed data on how students spent their time; future re search ought to be more elaborate in con twice and ceptualizing able (cf. Howard The university pare the amount this operationalizing 2005). also asks students to of time they spend to other classes they vari com on a have compared taken. Table 4 shows that 43 percent of course re students in my discussion-based more or more than much ported spending average, compared to only 7 percent of the students in my lecture course. By contrast, class 29 percent of the lecture course students time than average, reported spending to 9 percent of students in only compared course. Finally, stu the discussion-based course looked dents in the discussion-based less than stu forward to attending class more dents in the lecture course, despite the fact that the course content was the same. When course strongly pared to just 42.9 course students. Helping percent Students Learn agreed, of the com lecture Information I consider Although encouraging higher order thinking skills, fostering a democratic climate, and having students engaged with the course to be profound achievements in I also recognize that for many themselves, the bottom line faculty and administrators assessment for any pedagogy must be an measure of student objective learning. Given my course objectives and the types of mental activities and cultural sentiments I try to foster through the discussion-based course, it is difficult to create reliable meas ures of student learning across the two types of courses. So, I decided at the outset to use a blunt but reliable measure: I would simply student scores on the multiple compare choice component of exams. two midterm exams, I asked students in both courses the same multiple choice a random The questions were questions. On sample of the population of questions in the instructor's manual I edited for the textbook we used in class (Yamane 2002). These of the simply tested knowledge questions informational content of the course. A typi cal example is: to secondary What usually happens groups when A. There B. individuals exit and enter? is a change in the nature identity of the group They die out or 245 COURSE PREPARATION ASSIGNMENTS 3. Measures Table To what Culture of Democratic extent and Sense of Ownership by Type of Course do you agree with the following statements the about Level class/ instructor: (A)My individual contribu tion as a whole to the class was of Agreement % Strongly Agree/Agree Mean important (Std. Dev.) (B) Hearing the views and of other students experiences was an important part of the class (C) I benefited from hearing the views and experiences in the class students other of in students' view that were points unconven of or contradictory to the instructor's point of view tional (E) The ceptive instructor was re to questions (Std. Dev.) % Strongly Agree/Agree *p<.001 Categories/Coding: 5 = Disagree, 6 = 52.9 2.53a (1.10) (1.01) 1.82a (1.10) (.73) 1.79a (Std. Dev.) (1.12) (.72) % Strongly Agree 44.3 77.9 1.67a 1.22a (Std. Dev.) (.68) (.42) % Strongly Agree 61.4 86.8 1.40a 1.15a Mean 1= Strongly Strongly (.52) Agree, 2 = Agree, 4.19* 86.7 2.63a 88.2 5.07* 4.10* 4.70* 3.20** (.40) 3 = Tend toAgree, 4 = Tend to Disagree **p<.01 C. New groups branch off D. Nothing much The multiple choice questions simply tested the course's content. informational An improvement in multiple choice scores from the first semester to the second would mean that students in the second semester learned more informational content. Table 5 compares the students' perform ance in the two different courses. The aver age score on the first exam (15 questions) was 6 percent higher in the discussion-based and on the second exam (20 ques tions) itwas 11 percent higher in the discus course. These sion-based average differ ences are not overwhelming, but they are both and socially significant statistically a because 2-3 for student can (e.g., points mean the difference between a B+ and A course 22.9 3.29a 55.7 (Std. Dev.) aResponse Course 2.46a Mean Disagree, Discussion Course 52.9 Mean Mean (D) The instructor showed interest % Strongly Agree/Agree Lecture for the semester). These data suggest that the active and consistent engagement with the course material required in the discus course sion-based dividends-even paid looking just at the ability to memorize factual information such as that tested for on a multiple choice exam. Unfortunately, when the approach I took in creating these multi to choice exams does not allow me speak to the question of differential learning in different domains recall versus (e.g., was not Because it clear at the application). outset that there would be any difference ple between the two types of courses, I did not seek to test for learning at this level. The measure of student learning here is blunt, by design, but the results suggest that future efforts to use more complex measures of student learning are warranted. 246 TEACHING SOCIOLOGY Table 4. Student Time Spent on Class by Type of Course Lecture Course Discussion Mean hours spent on course per week (Std. Dev.) 3.8 5.3 (1.53) (1.29) Compared to other classes you have taken, how much Course tme did you spend on this course? Much more than average 0%11% More than average 7% 32% Average 64% Less than average 29% CONCLUSION predicated on students reading and thinking about the course material (receiving "first to attending class so that exposure") prior class time can be devoted to more advanced sure to the course material in discussion. this first expo is a series of These Preparation Assignments." a success in been have great assignments me to foster student my courses, allowing "Course of the majority by spending and coordinating, facilitating, rather than constantly leading discussions, lecturing at the students. I have used this strategy in introductory courses of 35 to 85 students that fulfilled a general education engagement class time requirement (and so had few majors) at two that consistently rank in private universities the top 30 of the U.S. News rankings. The this strategy remains of whether question can be adapted to different types of institu tions and courses. I used this strategy with under Although at elite universities, it could graduates In institutions. surely be used in non-elite fact, the strategy might be more effective in less elite institutions. As 9% citing research by Rau and Durand (2000), students at less selective institutions study far less outside of class than students in selective institutions. Some of this is cer in work obliga tainly due to the differences Nathan's tions; (2005) study of her own notes, Although many of us would like to get be lack concrete lecturing, we often yond in our for so, strategies doing particularly one such classes. This paper suggests larger a discussion-based for strategy creating course. The success of such a course is learning activities grounded The vehicle I use to achieve 48% Howard (2005) suggests that faculty need to be university aware of the time constraints some students face. Still, Howard (2004) "Just-in-Time-Teaching" has used approach, the which is similar to this one in its requirement of student work outside of class, at his 1,800 commuter campus student state university where students average 27 hours of paid work per week 2005:197). (see Howard The JiTT approach itself was pioneered by Uni faculty at Indiana University-Purdue a at 4 News U.S. Tier versity Indianapolis, to JiTT the university. Moreover, according hundreds of website (http://www.jitt.org), at of all types dozens of institutions faculty have adapted the method. I have taught 85 students in a Although discussion-based is a practical course, limit to I do believe there this implementing strategy in very large classes (of perhaps As noted above, 100 students or more). in such classes must consider instructors how much time they are willing to devote to if the class is grading assignments. Also, too large, many students will not have the opportunity to actively engage in the whole This defeats the purpose class discussions. course. Further of the discussion-based one of the biggest constraints on this more, 247 COURSE PREPARATION ASSIGNMENTS Table 5. Exam Scores by Type of Course Lecture Exam 1 Mean (15 points possible) Exam 3 Mean (20 points possible) 13.3 14.2 (1.00) 88 (.93) 94 Percent 14.4 16.6 (2.06) 83 strategy is the physical design of the class room. Both the small group and full class discussions work best in classrooms where students can move their chairs and can eas So, I always re ily see their classmates. chairs and quest classrooms with moveable no more than a couple of tiers. Unfortu nately, most classrooms that can Significance (1.82) 72 Score (Std. Dev.) Mean Course Score (Std. Dev.) Mean Percent Level of Discussion Course accommo date 100 or more students are auditoriums with stadium-style fixed seating which make if not difficult, any extended discussions impossible. the very large course, I believe Beyond in many this strategy can be implemented a courses of types serving variety of stu dents. The easiest way to adapt this ap proach is in the length and complexity of the written assignments and, thereby, the level at which the in-class discussions take place. Itmay be that less elite students who have large time commitments outside of class need shorter and simpler questions discussions. leading to less wide-ranging classes at all uni Students in upper-division versities may be able to handle more sophis ticated preparatory assignments and discus in sions than students lower-division classes. The same may be true of classes which enroll primarily majors compared to those service classes that enroll mostly non of level. Presumably majors, regardless students require less struc upper-division tured guidance than lower-division students, to pre and majors require less motivation pare for and participate in class than non majors. But even upper-division majors can so whether the assignments are disappoint, constricted or elaborate they give students a and motivation vehicle for engaging the to class reading material, coming prepared 5.45 .000 6.58 .000 for discussion, and ultimately becoming more actively involved in learning in gen eral. APPENDIX: COURSE PREPARATION ASSIGNMENT EXAMPLE Chapter 12 Course Preparation Assignment: Hypothesis on Racial Inequality inAmerica Introduction: Still an American Dilemma? In 1944, Swedish sociologist Gunnar Myrdal published a landmark study of American race He relations. maintained that the of principles equality at the heart of the U.S. Constitution with clashed the unequal treatment of African Americans which he observed historically and at the time he was was for Myrdal, This, writing. An American Dilemma (the title of his famous book). While the position of African-Americans (and other racial inequalities great interest minorities) remain. has since improved These inequalities then, are of to sociologists. Objective To describe quality and analyze in the contemporary Background Consider the following the causes of United States. from the U.S. data racial ine Census Bureau for 2001: Median Family Income Whites $47,041 Blacks $29,939 64 Percent of White Income 100 Assignment 1. Read Chapter 12 of the textbook on racial inequality to familiarize yourself with its 2. and consequences. causes, forms, at least five Generate testable you hypotheses believe might account for the differences income given above. In other words, the dif in TEACHINGSOCIOLOGY 248 are your are the independent with the hypotheses in income ferences able. What Note: Start most important or plausible; vari dependent variables? Christian, think you then on go Novak, to are In-Time list Hall. rival hypotheses that you think are less important or and would less plausible therefore to test want as a sociologist. Remember: since disprove want to testable you you generate hypotheses, as possible to be as specific in formulating need and your answers. Jossey-Bass. Brookfield, Stephen and Stephen Preskill. 1999. Discussion as a Way of Teaching: Tools and Techniques Democratic for CA: Francisco, San Classrooms. Adam 1991. Nystrand. Effects Instructional and "Background on 1:277-300. Aleksander. 1992. and "Management Pp. 108-43 in A History of the University in Europe, Vol. 1, Universities in theMiddle Ages, edited by Hilde de Ridder Symoens. Cambridge, England: Cambridge Resources." 1923. The Rise Charles Homer. Universities. New Jay R. York: Henry "Just-in-Time 2004. of Holt. 2005. Learning in Teaching "An of Examination in Introductory at a Com Sociology 33:195 Frank Kathleen, Beck, and Barbara Heyl. 2000. Sociology Through Active Learn ing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press. Student. Patrick Terenzini. 1991. CA: and San Jossey-Bass. sity Press. William Ann and Rau, Durand. 2000. "The Academic Ethic and College Grades: Does Hard Work Help Students to 'Make the 74:19-38. of Education Sociology Smith, Page. 1990. Killing the Spirit: Higher Education inAmerica. New York: Viking. Barbara Walvoord, and Lucille Parkinson 1991. Thinking and Writing in McCarthy. College: A Naturalistic Study of Students in Four Disciplines. Urbana, IL: NCTE. Barbara Walvoord, "Enhancing and Kristen 1998. Pool. Pp. 35 Productivity." Pedagogical 48 in Enhancing Productivity: Administrative, and Instructional, Technological Miller. CA: San Francisco, David. Steps to Successful ers Jossey-Bass. "Collaboration 1996. Discontents: Strategies, and Judith E. Toward Group and Projects." Its Barri Overcoming Teaching Sociology 24:378-83. ed. 2002. Instructor's Resource Manual Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press. McKeachie, Wilbert. 1999. Teaching Tips, 10th ed. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. What in the Rait, Robert. 1918. Life in theMedieval Univer sity. Cambridge, England: Cambridge Univer Newman. 205. Nathan, Research to accompany Sociology: Exploring the Archi tecture of Everyday Life, 4th ed., by David Student muter Campus." Teaching Sociology McKinney, and Ernest Pascarella, Yamane, Sociology or How I Convinced My Students to Teaching Actually Read the Assignment." _, Sociology 32:385-90. _. Achievement." and Literature edited by James E. Groccia Press. University Howard, Prentice Teaching of English 25:261-90. Grade'?" Jossey-Bass. and Martin in Eighth-Grade English and Achievement Social Studies." Journal of Research in Ado Haskins, NJ: and Adam Gamoran. 1991. Martin Nystrand, "Instructional Student Engagement, Discourse, Francisco, CA: San Francisco, Excellence. Gieysztor, Wolfgang 1999. Just College Affects Students: Findings Insights from Twenty Years of Research. 1985. Achieving Educational Astin, Alexander. lescence Gavrin, Patterson. Evelyn Saddle River, Teaching. How REFERENCES Gamoran, Andrew Gregor, and Rebekah. 2005. a Professor Ithaca, NY: My Learned Cornell Freshman University Press. Yamane Forest Littlefield Year: by Becoming at of sociology is assistant professor He is the author of The University. Pro in State Politics: Church Catholic Negotiating Realities and Political (Rowman & phetic Demands David Wake turalism: a Higher 2001). 2005) and Student Movements for Multicul in Color Line the Curricular Challenging Press Education (Johns Hopkins University