01 UL 2014 LIBRARIES

advertisement

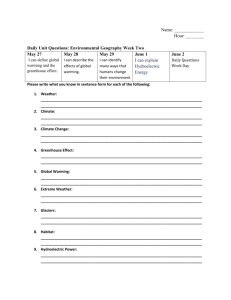

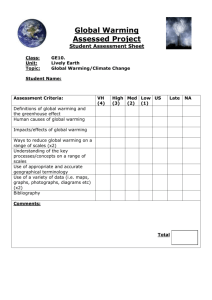

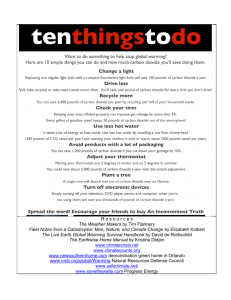

Investigating Anthropogenic Existential Risks through Art by Andrew Leigh Christie -1 -A S A I-IltW OF TECHNOLOGY B.ASc, Engineering Physics University of British Columbia 2004 UL 01 2014 LIBRARIES SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ART, CULTURE AND TECHNOLOGY AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2014 @2014 Andrew Leigh Christie. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature redacted Signature of Author: Department of Architecture, Art Culture and Technology MAY 15, 2014 Signature redacted Certified by: Renee Green Professor of Art Culture and Technology Thesis Supervisor Signature redacted Accepted by: Takehiko Nagakura Associate Professor of Design and Computation Chair of the Department Committee on Graduate Students E Investigating Anthropogenic Existential Risks through Art by Andrew Leigh Christie B.ASc, Engineering Physics University of British Columbia 2004 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE ON MAY 15, 2014 IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ART, CULTURE AND TECHNOLOGY ABSTRACT Through the creation of an art installation called Local Warming, and by analyzing energy-related art works by other artists, I was able to develop a methodology in my attempt to answer the question of what can be done about anthropogenic threats to humankind. Local Warming is a large array of 72 collimated infrared emitting robotic heaters that provide a "bubble" of heat energy around the user as they pass through the installation. This project serves as an example of how energy-technology development can seem threatening and can also be interpreted as the exact opposite: a system that provides us with direct control over our own energy. This serves as a metaphor for our relationship with energy on a global scale. While we may feel that anthropogenic existential threats, such as global warming, are beyond our control, I would argue that these threats are actually opportunities to improve our own understanding of the universe around us. Ultimately, the presence of a global risk can act as a common-cause around which humankind can rally and thrive. More specifically, my primary interest is provoking a conversation on how anthropogenic existentialrisks can be thwarted. My methodology has five repeating stages, in no particular order: identifying motivations, creating physical artwork, developing or borrowing a framework, establishing provocations, and reviewing the artwork of other artists who are creating similar work. For my motivations I make assertions that I do not intend to prove such as "human life is important" or "extinction is an undesirable outcome." The purpose of stating my motivations is not to create an argument about the meaning of life, but to help the reader understand my artistic practice as it relates to the topic of anthropogenic existential risks. The creation of a framework serves as a rudder to help guide the creative process. The questions that arise from the creation of this framework are then used as provocations. These provocations need not be iron clad or consistent in their logical makeup, and they often conflict in a way that produces tension. Lastly, the review of works by other artists enables me to put my own work into context. Thesis Supervisor: Renee Green Title: Professor of Art Culture and Technology 2 Motivation The thought of a universe with no intelligent life can evoke everything from depressive and lonely thoughts to complete indifference. This paper seeks to explore environmental and energy related risks to humankind. Through the analysis of select contemporary works of art, and by borrowing critical processes from sociology, philosophy, science and engineering, these risks will be illuminated. In addition, I will attempt to use my own creative practice to help add a layer of understanding that may not be easily expressed through any other means. Ultimately, I wish to answer the question: "what can be done about anthropogenic existential risks to humankind?" While I cannot say with any certainty that I know the answer, this paper documents my methodology, my motivations, my provocations and my physical project based attempt in the form of an installation called Local Warming. My motivations to innovate come from a deeper desire to create positive change in the world. While I am completely aware of the grandiose and subjective nature of this endeavor, I take it as a fundamental assumption that the proliferation and long term survival of creative intelligent life is a fundamentally desirable outcome for humankind. To help the reader better understand my intensions, I will define my own primary motivators as follows: Motivator 1- The fear of dying after a meaningless existence. Or, as an abstraction, the fear that we will forever be the only intelligent species in the universe. Should we become extinct, there is a finite chance that no self-aware culture producing species will take our place and that existence will cease to have meaning. Motivator 2- An acute awareness of how fragile and insecure we are as well as the desire to overcome these fragilities. From this we can extrapolate that as a single entity, humankind is similarly fearful of our precarious existence on our one and only world: Earth. 3 CreatingPhysical Artwork: Local Warming Local Warming is my attempt to create a immersive experience that gives the user a direct and visceral interaction with heat energy while at the same time offering a sense of optimism and wonder in contrast to what would otherwise seems to be threatening. On a practical level, heating systems generally waste an extraordinary amount of energy on heating empty offices, homes, and industrial buildings. Local Warming addresses this inefficiency by harmonizing heating systems with human occupancy. An array of 72 dynamic infrared heat "spotlights" are guided by location data provided by WIFI tracking the user's mobile phone. The effect creates what appears to be a localized personalized climate for each user. These individual "heat bubbles" follow the users through a room, providing them with control over their own comfort while improving energy efficiency. When thought of as a responsive environment, Local Warming exhibits a smart, data-driven, personalized form of climate control. The installation can act as a metaphor for how we can either interpret a complex system that is driven by technological innovation as oppressive, or as an enabling system that brings us closer to understanding how energy systems work. One might interpret the "spotlight of heat" as an acting agent at a distance that can impose it's will upon us. But with the advent of a mobile phone we can invert this relationship and come to understand that the device itself is completely within our control. In future versions of Local Warming, we will be able to set the temperature as we please. Likewise, the WIFI tracking can be turned off as the user pleases. The following images offer a glimpse at the process of "making." In this process, I borrowed heavily from my engineering background and from my ability to fabricate and manufacture parts and assemblies. The overall design was created in a CAD package called SolidWorks. The units and arrays were fabricated using the machine shop in the ACT and Center For Bits and Atoms machine shops inside the MIT Media Lab. I was assisted by 25 undergraduate students over two years in the process as well as three full-time research assistants. Most of the financial support was provided by the SENSEable City Laboratory with some supplemental support from CAMIT. The process of making helped me think of new ideas, provocations, hypocrisies, fears and questions that would ultimately guide me to write this paper and help me integrate through all five stages of my methodology: asses motivations, create physical artwork, develop a framework, establish provocations and review the work of similar artists. These stages were not followed in any particular order and each stage was revisited many times throughout the project. Local Warming will be installed as part of the "Elements of Architecture" exhibit, curated by Rem Koolhaas during the 2014 Venice Biennale. 4 Can I beam energy at people? What is real energy? Will it make them warm? Will they feel that it is their own personal energy? Will they feel empowered? Will they feel comfortable? 5 t Can I reject visible radiation? Can I do so with a cold mirror? Can I permit only infrared to pass through? 6 Can I melt the snow? 7 Can it be a spotlight of heat? Can it be a collimated beam? Can it project heat at large distances? 8 Can I actually build it? Can I test it? 9 How long would it take to build? I had six helpers here yesterday, why am I here in the shop all alone? 10 Why does this not really look the way I wanted it to? Does it matter? What am I really trying to do? Make art? 11 Is this really great? Why? Does it seem small? 12 Should I try something new? Should I try something stationary? 13 Should I manipulate the light? What if this will never help anyone? 14 How much energy does it take to laser cut? What's the point of developing anthropogenic solutions when device production consumes so much energy? If I make a new product and develop a new concept, will anyone care? Why am I still doing this? How is this second prototype anything different from an engineering project? 15 Why am I dreaming of waterjet cutting? 16 Why is this so bright? 17 Why can't I stop thinking about arrays? 18 Can manufacturing be creative? 19 Why not? 20 What motivates me? Why am I not satisfied when something finally works? Why do I care so much what other people think? 21 How many hours have I put into this? Was it worth it? Why is it worth it? 22 Why does it feel good to control a machine? 23 I Why does it feel good to produce? 24 Why does it feel good to build tools? What is so special about power? 25 What is so good about automation? 26 Why does everything I do use so much energy? Why does this not look right? Should I care? How important are aesthetics for a project like this? 27 Why do I care so much about energy? 28 How many generations after I die to I care about? 29 One- 30 N, Two? 31 Infinite? 32 Local Warming and Energy-Awareness The above photos and thoughts are a representation of the process of innovation that I developed while exploring the creative use of energy. The photos contain a glimpse at my raw and uncensored thought process. I am self-conscious about my childlike wonder . surrounding technology and science, but I feel that it is also central to my creative process. For the past seven years my primary focus has been the scientific and technological analysis of the production and consumption of energy in the context of sustainability and "the greater good." My efforts, however, were in vain. Without fail, no one really seemed to care. Energy was always an afterthought, and the environmental damage of energy production was always a necessary evil. As an oversimplification I asked myself, "what if we use up all the resources in such a way that we forever doom future generations to either a mediocre existence or extinction?" Local Warming is my attempt to materialize and manipulate energy in an immersive manner. Energy is a lot easier to understand and relate to when anyone and everyone is able to control it. However, today I find myself less in control of energy than ever before. I have little or no say on how North America chooses to produce energy, and it's nearly impossible to tell people how to use it. We are destroying ourselves, and there is nothing I can do about it. I feel alone, confused, and powerless. Local Warming brings me comfort, warmth and hope. If I can create a device that can beam energy to anyone, at anytime, at any distance, in such a way that it is completely controlled by the user, what would that mean for society? How would we change the way we think about threats such as Global Warming? How would we change the way we behave? How would we change the way we produce and consume energy. I need to fundamentally understand what is going on in the grand scheme of things. I need to dig as deep as I can possibly go to understand what threatens humankind, and how those threats can be thwarted. The path that I have taken to this point is convoluted and confusing, but I feel that these traits serve only to the detriment of my creative practice. The bulk of this written work aims to shed light on my through process and how my innovations come to fruition. The starting point of which comes from a deep frustration with the complexities of what could be described as a "world of threats" where inaction is the norm. You can't simply yell at people and tell them what to do in order to prevent certain disaster. It does not work. The following will shed light on anthropogenic existential risks, and my own process for understanding and hopefully thwarting these risks. 33 Developing and Borrowing Frameworks Primary Scientization - Framework idea #1 While technological progress often resulted in new threats on a local level during premodern times, it was unlikely that a new technology posed a threat to all of humankind. Ulrich Beck describes what followed as primaryscientization,otherwise known as the enlightenment of Western civilization. The development of unforeseen risks and side-effects as a result of primary scientization results in what Beck refers to it as secondary scientization or reflexive scientization'. We transitioned from society facing primary risks (feudal traditionalism) to one that faces probabilistic or estimable risks that are a product of the same forces that created the risks in the first place. As an example of this transition, Beck writes "If we were previously concerned with externally caused dangers (from the gods or nature), the historically novel quality of today's risks derives from internal decision" 2 . Existential Risk - Framework idea #2 Qualities that have led us to produce and consume energy and materials at exponentially increasing rates have historically been considered to be evidence of our collective superiority, but are now in direct conflict with the possibility that we are becoming more vulnerable than ever to existential risks or, the possibility of a global terminal disaster annihilating our entire species. Nick Bolstom defines existential risk as "one where an adverse outcome would either annihilate Earth- originating intelligent life or permanently and drastically curtail its potential." 3 Bolstom clarifies that the reflexive version of this type of risk is relatively new in that, for most of our existence, human kind has not been a serious threat to itself. With the exception of a species-destroying comet or asteroid impact (an extremely rare occurrence), there were probably no significantexistential risks in human history until the mid-twentieth century, and certainly none that it was within our power to do something about4. Anthropogenic Climate Change - Framework idea #3 The most poignant and well understood anthropogenic risk is that of climate change. We will take it as a fundamental assumption that this risk is grave and near term and that the reader needs no convincing. The precautionary principal alone should be sufficient motivation for swift global action to create positive changes in the way we produce and consume energy. But in the face of overwhelming evidence that not only is anthropogenic climate change a near term risk to our economy, health and way of life, but that there is a 1Ulrich Beck, Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity (London [u.a.]: Sage, 2007). 2 Ibid. 3 Nick Bostrom, "Existential Risks: Analyzing Human Extinction Scenarios and Related Hazards," Journalof Evolution and Technology, Vol. 9, No. 1 (2002), http://www.nickbostrom.com/existential/risks.html. 4 Ibid. 34 very real possibility that it's effects could annihilate our entire species. In Bolstom's words, such a disaster would be, by definition, "global" and "terminal." The failure of the Kyoto Protocol and subsequent efforts to curtail C02 emissions would indicate a tragedy of the commons on an unprecedented level. Assuming we can trust the scientific consensus, and that we know what the likely and possible outcomes are, how can it be that we have reached such a perplexing state of paralysis? Perhaps it is the lack of a precedent that is part of the problem. Latourian Approach - Framework idea #4 In "Love Your Monsters" Bruno Latour uses Frankenstein as the classic cautionary tale against the unintended consequences of technology development. Latour writes, "We use the monster as an all-purpose modifier to denote technological crimes against nature."i Much like Dr. Frankenstein's ghastly reaction and subsequent abandonment of his creation, we have reacted to global warming in a similar way: our collective inaction and apathy following the unintended consequences of rampant resource consumption has been horrifying. Considering the advent of scientific consensus, global institutions, and ample plausible solutions, why is it so hard to tame our climate change monster? Part of the answer lies in the history of the scientific process itself. The example given by Latour is that of Robert Boyle's air pump where "Boyle carefully refrained from talking about vacuum pumps" and "claimed to be investigating only the weight of the air without taking sides in the dispute between plenists and vacuists.""i It was the object itself and the indisputable facts that emerged from experimentation with this object that made a deeper understanding of nature possible. Furthermore, the object lent credibility that was independent of the desires and dogmas that one might accuse the scientist of harboring. The triumph of reason over tradition allowed scientists to avoid political debate altogether and focus on uncovering the "instrumentalized nature of the facts."li We can then take comfort that "these facts will never be modified, whatever may happen elsewhere in theory, metaphysics, religion, politics or logic."iv Presumably, from this scientifically fortified position, we can then be successful at tackling local and global problems that would otherwise remain unsolved. Or, at least this is how the modern narrative goes, but clearly something has gone wrong. Ozone Layer - Framework idea #5 Is there a suitable precedent for a global threat such as climate change? Is there a case study where scientific consensus led to effective globally coordinated solutions and policies? One example is the successful international regulation of ozone depleting substances. While the thinning of the ozone layer is not yet solved, considerable slowing has been achievedv. The problem is global in scale, and in order to prevent further damage scientists had to convince policy makers across the majority of industrialized nations to self-impose regulations on their industries. The facts had to reveal the "nature" of the ozone layer as being susceptible to human influence and that its contents could be modeled and predicted with sufficient certainty to take action. However, Latour contends, "the ozone hole is too social and too narrated to be truly natural."vi In other words, it was not just the scientists who enabled global action, the solution involved considerable interactions between scientists, policy makers and the general public. One would hope that this coordinated approach could serve as a precedent for action on a global scale when it comes to an environmental issue that involves emissions. One would think that the same pattern would apply when tackling similar large-scale problems. Given that today "We run robots on Mars" and "dream of 35 further galaxies" how is it then that "we fear that the climate could destroy us"?vii So what is different about global warming? The Failure of Scientific Discourse Framework idea #6 How has scientific discourse failed to unite the world in the belief that anthropogenic climate change is real and immanent? It is tempting, at first, to simply blame the science as being inaccessible to the general public. However, these issues are entangled in a way that requires a deeper and more nuanced investigation. Latour writes, "everyday in our newspapers we read about more entanglements of all those things that were once imagined to be separable -- science, morality, religion, law, technology, finance, and politics. But these things are tangled up together everywhere: in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, in the space shuttle, and in the Fukushima nuclear power plant."viii Latour offers us critical tools to help understand the connections between the sciences and politics. "We too have to take laws, power and morality into account in order to understand what our sciences are telling us about the chemistry of the upper atmosphere."ix However, more recently Latour has found that these critical techniques have been used to obscure the facts; there is a danger in dismissing scientific facts as mere social constructions. "Entire Ph.D. programs are still running to make sure that good American kids are learning the hard way that facts are made up, that there is no such thing as natural, unmediated, unbiased access to truth, that we are always prisoners of language, that we always speak from a particular standpoint, and so on, while dangerous extremists are using the very same argument of social construction to destroy hard-won evidence that could save our lives."x Latour describes Global Warming as an "artificially maintained scientific controversy."xi Latour asks "what were we really after when we were so intent on showing the social construction of scientific facts?"xii Latour elaborates in "Pandora's Hope" by describing the reaction of some scientists to his approach: "What I would call 'adding realism to science' was actually seen, by the scientists at this gathering, as a threat to the calling of science, as a way of decreasing its stake in truth and their claims to certainty."xiii "In my view, your work and that ofyour many colleagues,your effort to establishfacts, has been taken hostage in a tired old dispute about how best to control the people. We believe the sciences deserve better than this kidnapping by Science."xiv By being skeptical of the sciences we are opening up the possibility of abuse by political actors who have a vested interest in the status quo to the extent that they are willing to bend or ignore the facts. Or worse, we open ourselves up to abuse by those who are scientifically illiterate. Blind Darwinian Process - Framework idea #7 At this stage, it is tempting to think that the solution is to simply let the war play out and to allow the truthful concepts to gradually overcome the fallacies. If a certain social construction is more beneficial to a given culture or civilization, then surely that idea will propagate as the benefits of this better understanding play out through economic, technological and other benefits such as increased health. However, Latour clarifies that this 36 is the wrong approach. "Why not let the 'outside world' invade the scene, break the glassware, spill the bubbling liquid, and turn the mind into a brain, into a neuronal machine sitting inside a Darwinian animal struggling for it's life."xv If ideas are either social constructions or facts, why not let the various understandings of reality (and the decisions that go with them) compete with one anther in Darwinian fashion? While this method of determining the most effective system of understanding would surely work on a cosmological scale, for the case of global terminal disasters, this is not a good option since the triumph of one social construction over another may not occur until the disaster has already struck! Latour concludes "a blind Darwinian process that would limit the mind's activity to a struggle for survival to 'fit' with a reality whose true nature would escape us forever? No, no, we can surely do better, we can surely stop the downward slide and retrace our steps, retaining both the history of humans' involved in the making of scientific facts and the sciences' involvement in the making of human history."xvi If not the brute force of scientific consensus, or the heartless approach of a Darwinian competition, what technique should we then use to develop the best approach to thwarting global warming? What should our approach be in tackling the problem of climate change? The answer may reside somewhere in the analysis of the relationships between politics, science, and technology. While preserving the benefits and scientific advances of modernity, we must create mechanisms to monitor and analyze the social constructs that go beyond these facts, such that we can unravel the complex mechanisms where information is believed and is applied to policy. We must continue to measure the changes in nature such as the changes in global temperatures, melting of polar ice, C02 levels in the atmosphere, and then take these entities and treat them as objects and observe how they change public opinion. By recognizing that changes in nature become dynamic and influential entities in the global debate, we may find that a solution can be found. In combination with a careful analysis of the complex interactions between the sciences, politics, and technology, this approach may allow us to uncover potential sources of paralysis and counterproductive arguments. 37 Array of Provocations Individualism and Death - Provocation #1 Armed with a Latourian "hybrid" approach, we can now return to the motivations proposed earlier and analyze some of the contributing factors that have led to the current state of affairs. I will propose, but not prove, a simple idea to help limit the scope of risks to be analyzed. What can we learn about human motivation through culture? And conversely, what can we learn about collective paralysis by studying culture and art? The production of culture is certainly correlated with survival and death5 . Can death, or fear of death, help us to understand the collective will of humankind? The modern definition of culture is simply "the arts and other manifestations of human intellectual achievement regarded collectively." They word "achievement" implies having a purpose and a sense of progress. The word culture comes from the Latin word "cultura" meaning to "convert solar energy into nutritional energy consumable by humans"; otherwise known as agriculture. Assuming that the need to survive has been the most consistent historical source of motivation for humans, we can also assume the collective motivations to prevent the deaths of our future offspring and the offspring of others has been a lower priority. A question that sheds some light on this issue is "How many generations after I die do I care about?" How can motivators 1 and 2 (above) fit in with a world that is still suffering from disease, poverty, war, and famine? And why is it important or interesting to investigate these forms of motivation? Apex Predator - Provocation #2 The human race has evolved, through natural selection, to have characteristics that promote the survival of the individual their offspring. Through trial and error humans have evolved genetically, technologically, and culturally such that we have attained apex predatorstatus 6. However, many of the same traits that allowed us to flourish in the Pleistocene have now become threats to our existence in the Anthropocene . Where we once felt justified and dominant in our collective ability to harness energy and materials from the earth for our growth in population and technological capabilities, we now find ourselves in a state of constant threat from the side-effects of our own expansions. Collective Global Response - Provocation #3 On a local level, when discussing threats we think of war, disease and famine. The culture implications of such things manifest themselves through the collective desires and fears of a geopolitical region. It would seem silly, for example, to impress upon someone who is starving or dying of an infectious disease in a war-torn country how important it is to think s Marvin Harris, Cannibalsand Kings: Originsof Cultures (Toronto, ON: Vintage, 1991). "Evolution and General Intelligence: Three Hypotheses on the Evolution of General Intelligence," Scientific American (October 30, 1998), https://www.csulb.edu/-kmacd/3461Q.html. 7 Andrew C. Revkin, "Confronting the 'Anthropocene'," Dot Earth Blog, accessed December 3, 2013, http://dotearth.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/05/11/confrontingthe-anthropocene/. 6 38 about energy conservation for future generations. When we talk about culture in the context of human achievement we do not typically extrapolate the topic to encompass the will of humankind. It's far easier to discuss the role of the individual, the inclinations of tribes or nations, the fanaticism of religious leaders, the creativity of artists and the legacy of writers. It is for this reason that I will aim to shed light on the collective intensions and motivations, in contrast to individualist motivations. This paper will largely ignore the wants and needs of specific individuals and focus on the larger psychological and existential needs of our collective hive-mind. This is not to say that the needs of the individual are not important, or even less important than the collective needs of future generations. I will treat humankind as a long-lived single entity with pluralistic tendencies: a ferocious appetite for innovation, a need to explore, a desire to find companionship and a deeply engrained fear of extinction. Humankind is at the mercy of behavioral patterns developed over thousands of years of evolution. Much like a hormone-poisoned teenager, this single entity simultaneously battles with nihilism, narcissism, and self-destruction. Until recently, humankind had a poor sense of the limits of our own growth. Gaia Theory and Spaceship Earth - Provocation #4 Treating the human race as a single entity with a single lifespan is similar to how the Earth has been described as a single living entity by James Lovelock: Living matter, the air,the oceans, the land surface were parts of a giantsystem which was able to control temperature,the composition of the air and sea, the pH of the soil and so on so as to be optimum for survival of the biosphere. The system seemed to exhibit the behavior of a single organism, even a living creature8. In contrast to this biological conception, Buckminster Fuller describes our planet as Spaceship Earth: One of the interesting things to me about our spaceship is that it is a mechanical vehicle,just as is an automobile. Ifyou own an automobile,you realize thatyou must put oil andgas into it, andyou must put water in the radiatorand take care of the car as a whole. Regardless of ones metaphor or analogy, there is some value in thinking of our existence on earth from a holistic perspective. It enables us to consider long-range threats on time scales much larger than our own lifespans. If we assume that there is substantial value in ensuring a high quality of life for our children, grandchildren and every generation that follows, then these metaphors serve as a practical guide when examining the question: what does it mean to survive? Fermi's Paradox - Provocation #5 Should we fear that we are alone? And what is so special about Earth? Fermi's Paradox is the apparent contradiction between the large predicted number of inhabitable planets that are older than our own and the fact that we have not been contacted by extraterrestrial life. A careful combination of biodiversity, atmosphere, water, and abundant life-enabling 8 James Lovelock, "New Scientist," February 6, 1975. 9 R. Buckminster, Snyder, Jaime Fuller, OperatingManualforSpaceship Earth (Baden, Switzerland: Lars Mller Publishers, 2008). 39 elements like carbon made it possible for the emergence of human life. The Earth itself came into existence 4.54 Billion years ago, and life "shortly" thereafter at around 3.8 billion years ago. The Solar Nebula Hypothesis suggests that Earth formed from what was then a very spread out form of our modern day sun. As heavier metals clumped together the inner planets of our solar system formed. Thus, in a sense, both the matter and energy required to create Earth as we know it came from humankind's unrivaled source of energy: the sun. Above all else, the human race is dependent on abundant energy to exist. And perhaps most importantly, as Michael Perryman explains, "planetformationappearsto be a naturalbyproduct of the very process of starformation,which is ubiquitous and ongoing throughoutthe Universe.10 " With this energy has come a sense of collective ownership. The sun is "our star" and our plenitude, scientific progress, technology, culture, and art are all a result of this stellar gift. It belongs to us all, and yet the distribution of energy throughout different regions of the world and different socio-economic groups is tremendously unequal. Furthermore, it's difficult to grasp this sense of energy ownership in a world where we are so disconnected from the intricate systems upon which we depend for our current quality of life. When one sets foot into a building one does not become aware of who "owns" the heat energy they are borrowing. We simply warm or cool our bodies as a result of the temperature that is controlled by the buildings various energy systems. Not only do we not have any awareness of how much of this energy we are individually responsible for, it's rare that we ever really know where the energy comes from. The lengthy chain of machines, technology and transductions that take place to make it possible for us to live the way we do is largely ignored by all but the occasional engineer, scientist or building manager. The food supply chain is similar and the fuel we use for our vehicles is only slightly better understood. The trend, however, is clear: when we take responsibility for our own energy, much like one does in an apartment where the bill is paid by the same person who controls the thermostat, we become much more aware. This is accomplished primarily through the price of energy. I intend to show that the problem is a fundamental disconnect between culture and energy. This problem exists as a barrier to our collective understanding of what it means to progress. In relation to our survival as a species, this disconnect has done a tremendous disservice to our grandchildren and great-grandchildren and every generation that follows. What is Progress? - Provocation #6 Why should we seek to make changes at all? What is the advantage of gaining a deeper understanding of our personal relationships to energy? If we look at the history of these kinds of questions, we are quickly led down a path that reeks of hegemonic powers, paternalism, westernization, and techno-optimism. To even begin to discuss art in terms of having an agenda, we first either have to conceal our true intentions in a barrage of esoteric psychobabble, or through deliberate deception. Or we have to show our hand and reveal our true intentions, thus leaving ourselves vulnerable to scathing criticism. Staying true to my scientific erudition, I have chosen the latter. And thus, we will first discuss progress. 10 Michael Perryman, "The Origin of the Solar System," arXiv:1111.1286 (November 5, 2011), http://arxiv.org/abs/1111.1286. 40 Historically, the idea of progress is a set of theories that explain quality of life can be improved through advances in science, technology and economic development1 1 . But happiness is hard to measure and progress is often discussed in terms of expansion and economic growth. Measurable indicators such as gross domestic product, and income percapita were developed. However, inequities in wealth led to the happiness of the few and the misery of the masses. In the late 20th century, a new approach was adopted which combined life expectancy, education, and standard of living (GNI per capita) 12. With this new system, it was thought that we could be confidant in our goals and proceed unfettered. But once again, a flaw was discovered. In a world of finite resources on a single planet, how could we continue to progress indefinitely? In a world where our planet's resources are completely decimated, the "idea of progress" ceases to have meaning. What good is it to grow when our planet is a wasteland and our chances of survival as a species are near-zero? Fortunately some of these problems have been addressed by the Millennium Development Goals where goal 7 is "ensuring environmental sustainability"13. Jevon's Paradox - Provocation #7 Increasing the efficiency with which a resource is used, through technological progress, tends to increase the rate of consumption of that resource. This phenomenon has come to be known as "Jevon's Paradox"14 . It is used as an argument for why technology and science are ill-equipped to help us deal with existential threats that come from humankind's tendency to over-consume. Many believe that humans are like locusts plaguing our biosphere or like a cancer that has infected the Earth and has to be irradiated. Some would suggest that we are not the solution, but the fundamental source of the problem. We face many existential threats such as global warming, peak oil, decreasing planetary biodiversity, and our inability to accurately detect and thwart the impact of a large asteroid. These challenges can be sources of inspiration rather than pessimism. In the face of existential threats, the world can unite and thrive. In the face of existential threats, can art and culture facilitate an intuitive and intertwined understanding of our energy systems? Exponential Growth - Provocation #8 The unprecedented population and economic growth that humankind experienced, from the enlightenment to present, is exponential in nature. A great deal of investment has gone into what many refer to as "sustainable growth." The fundamental idea is that if we learn how to harness technology and curtain the harmful effects of growth that we can continue to expand as we have. That said, our planet has finite resources and basic logic would lead one to the conclusion that such an expansion cannot last forever. Dr. Albert Bartlet describes the exponential nature of growth when he says, "Sustainable growth is an oxymoron." The proposed alternative is commonly referred to as "resilience." The principal idea is that humans should reduce our impact on the planet by reducing our population. The 11 Robert A. Nisbet, History of the Idea of Progress (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1980). 12 Jeni Klugman, "The Real Wealth of Nations: Pathways to Human Development" (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010). "United Nations Millennium Development Goals," accessed May 11, 2013, http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/environ.shtml. 14William Jevons, Coal Question, 3 Reprint (Cambridge, England: Augustus M Kelley Pubs, 1906). 13 41 ethical implications of actively killing humans or allowing them to perish when they could otherwise be saved are overwhelming. The more-ethical alternative is to slowly allow the population to decrease by enforcing lower global birthrates. World population growth peaked sometime in the 1960s. Furthermore predictions show a peak population between 8 and 12 billion will be reached sometime within the next 100 years15. Malthusian catastrophe - Provocation #9 One predicted consequence of overpopulation and un-checked consumption of resources is referred to as a Malthusian catastrophe 16 . Much like bacteria in a petri dish, the shape of the population curve over time might grow exponentially until a resource limit (such as food) is reached at which point a sharp decline in population results. A New Definition of Progress - Provocation #10 Does a halt in population growth imply the end of economic progress? Not necessarily. Holding the long-term survival of the human species as a fundamentally important axiom, one can imagine a world that continues to "grow" scientifically, culturally, and in terms of planetary biodiversity. A greater sense of the long-term view is now emerging. We are discovering that the rate at which we are able to create and destroy things is rapidly increasing. We are experiencing regular shifts in optimism and pessimism. Much like a global hangover after a night of binge drinking, we are learning to cope with our newfound sense of power. "I think most people would agree that afuture where we are a spacefaring civilization is inspiring and exciting compared to one where we areforeverconfined to earth until some eventual extinction event" -Elon Musk Intelligent Life is Important - Provocation #11 What is so special about humans? Is our DNA in control? And if we are going to mutate as a species, and we know this for certain, why try to preserve our genetic and cultural whole? We have a certain genetic inertia and cultural inertia that we take for granted. It may be that what we are truly protecting is the long-term survival of intelligent life in general. We are simply unaware of any other species that is able to contemplate and perhaps thwart its own extinction. One could argue that we have a responsibility not to waste what may turn out to be a unique opportunity. Earth Vs. Humans - Provocation #12 Deep ecologists (or "Dark Green" environmentalists) adhere to the fundamental idea that our Earth will likely recover long after we become extinct. As a system of values, this form of thinking places biodiversity at the helm. Much like Gaia theory, the earth is treated like an intelligent and living creature as a massive interconnected super species. Much like the trillions of cells within the human body, the Gaian Earth is composed of its diverse species. 15 Wolfgang Lutz, Warren C. Sanderson, and Sergei Serbov, The End of World Population Growth in the 21st Century: New ChallengesforHuman CapitalFormation and Sustainable Development (Earthscan, 2004). 16 Thomas Robert Malthus, An Essay on the Principleof Population:Or, A View of Its Pastand PresentEffects on Human Happiness (London, England: Printed for J. Johnson, by T. Bensley, 1807). 42 Is humankind unimportant in comparison to the Earth? It's far more productive to think of them as equals; regardless of intrinsic value, it can be said that a planet with strong biodiversity is more likely to ensure a longer-term survival of humankind. Our futures are inextricably linked, thus we are better off treating biodiversity as equally important as any other human endeavor. I consider the promotion of biodiversity as a fundamental component of human progress. Protest Art - Provocation #13 While the topic of human extinction is a big topic and provokes grandiose fantasies of space colonies, cures for cancer, and sustainable utopic societies, more often than not it simply generates "protest art." Whenever a new fad threat suddenly gains in popularity in the media, art trends will surely follow. There is a long history of magazines such as AdBusters. These works generally focus on normative topics. Protest artists urge that things "ought to be" a certain way, and that the status quo is "evil" or "unsustainable." Threats such as peak oil and global warming are warned about in films such as "An Inconvenient Truth" (by Al Gore). As a scare tactic, this approach can motivate millions and can often create real change. However, I will argue that it does very little to foster an intimate connection between energy and culture. Responsibility of the Artist - Provocation #14 One might argue that artists should be free to create whatever they want. Why does art have to have a purpose? Scientists have a responsibility to unravel the truth about our universe, and civil engineers are sworn to never design and build structures that are dangerous. What is different about artists? Kardashev Scale - Provocation #15 The Kardashev scale is a framework for describing the amount of energy a given civilization is able to harness. The scale is composed of three levels: Type I, II and III. Type I civilizations have successfully harnessed all of the energy available to their home planet. If they are able to harness the total energy of their local star they are considered Type II. And once able to utilize the sum of all energy in their galaxy a civilization would be considered Type 11117. We will use K1, K2, and K3 for short. Dyson Spheres: Interstellar and Intergalactic Energy Collection - Provocation #16 To become a K2 or K3 civilization a very large number or collection of energy harvesting devices would have to be deployed. As radiation is emitted from stars in roughly spherical patterns with sub-fusion temperatures occurring at a relatively large radial distance from the center of the star, these systems would have to be immense. A solution was proposed by a physicist named Dr. Freeman Dyson 8 . A Dyson Sphere is a large energy collection mechanism that can be composed of a very large number of satellites or rings that ultimately absorb every useful quanta of energy emitted from the local star. 17 Nikolai S. Kardashev, "On the Inevitability and the Possible Structures of Supercivilizations," in The Searchfor ExtraterrestrialLife: Recent Developments, ed. Michael D. Papagiannis, International Astronomical Union 112 (Springer Netherlands, 1985), 497-504, http://ink.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94009-5462-5_65. 18 Freeman Dyson, Selected Papersof Freeman Dyson: With Commentary (USA: American Mathematical Soc., 1996), 555. 43 Example of Dyson Sphere artwork.19 Keep Quiet - Provocation #17 One proposed solution to Fermi's Paradox is the possibility that all successful and advanced extraterrestrial civilizations have learned to keep quiet for their own self-preservation. It's possible that all advanced extra-terrestrial civilizations are self-selecting to be "silent" to thus hide their existence from other potential competitors. In such a scenario, it may be that the only civilizations to survive might be the ones who have gone undetected by other predatory species or Von Neuman Probes 20 .If this were true, surely some of them would advance to become a K2 or K3 type civilization. This leads us to why Dyson Spheres are important to unraveling the great mystery. Their hypothetical existence is a potential solution to Fermi's Paradox. It's nearly certain that a Dyson Sphere would emit large amounts of infrared radiation, to such an extent that its signature could be easily detected should our infrared-sensitive telescopes focus on that particular star or galaxy that is enclosed by such a superstructure. The energy collection system would absorb and reradiate the waste energy as heat (infrared). The findings, so far, have come up empty handed and it's certainly possible that no such structures exist anywhere in our universe. Thus, if we are to believe the hypothesis that ancient and advanced K2 and K3 civilizations have remained quiet, we should be able to detect the infrared signature of their Dyson spheres. This lends credibility to the idea that the greatest threat to advanced life forms is resource depletion. It could turn out that every species that Adam Burn, SHield World Construction,digital, February 26, 2009, http://adamburn.daportfolio.com/gallery/124232#10. 20 Robert A. Freitas Jr., "A Self-Reproducing Interstellar Probe," A Self-Reproducing InterstellarProbe,1980, http://www.rfreitas.com/Astro/ReprojBlSjuly1980.htm. 19 44 has ever existed has encountered a Malthusian type of fate. Or it could be that we are unique in that we are the only species that can contemplate our own existence. We may be alone in our ability to thwart our own extinction. 45 A Different Approach - Artists Making Similar Work Despite the advent of advanced technology and a deeper scientific understanding of our universe, the body of artistic research surrounding energy issues is relatively undeveloped. The following are examples of works of art and in some cases design projects that, to varying degrees of success, provoke discussion and thought about energy and existential threats to humankind. These works can materialize energy and environmental issues such that they transmute into ingrained patterns within our collective consciousness. Theo Jansen's "Strandbeest" series of sculptures are wind powered walking machines. Jansen has iterated upon their design over several decades. Treated by the artist as life forms, the goal is to have them evolve to the point where they can survive on the beach without human intervention. One way to interpret Jansen's work is to question what it means for an artificial life form to exist with wind as its sole source of energy. His works are poetic, and incorporate a relatively rudimentary selection of technologies. His creations are essentially autonomous robots with no electronic controls or computer programming involved. His stated goal of creating artificial life forms contrasts with the relatively organic forms he creates in such a way that one is forced to question: does the creation of new life necessitate technological progress as we know it in the 21st century? Strandbeest fails at artificial intelligence, but succeeds at inspiring awe regardless of ones comfort level with advanced technology. If his material choices were similar to those of a military attack drone, it's unlikely that the impact would be as disarming. After several hours of operation, Jansen's Strandbeests are unable to continue functioning and require human-intervention to re-animate. 46 Theo Jansen's Strandbeest (Photo by Jeff Lee Petry) 21 . Automated fabrication and the direct utilization of solar energy come together in Markus Kayser's Solar Sinter project. Much like a Von Neumann machine, the sintering device can take raw, and virtually inexhaustible materials, and directly convert them into useful objects by harnessing solar radiation directly. No conversion of energy to electricity is used in the sintering process other than the negligible power required for the control electronics. Much like Jansen, Kayser successfully portrays both the process and form through poetic and stylized video footage. He disarms the viewer by creating a stark contrast between the minimalist natural environment, in this case an Egyptian desert, and the alternative energy robot aesthetics of the solar sintering machine. The work of art is an amalgamation between the tool, the art-object, and the process. In this case the art-objects are the bowls and architectural forms created through the solar sintering process. Had Kayser chosen to create objects from sand by harnessing the power of oil or coal the meaning would be lost. Likewise, had he sintered aluminum with solar power, the concept would fall flat. It is the incomprehensible abundance of both solar energy and sand that forces the viewer to consider a future that we might have otherwise discounted in the face of paralyzing resource pessimism. Kayser's approach differs with that of Jansens' in his use high-tech Theo Jansen, Strandbeest,Plastic, fabric, 2012, http://eatart.org/wpcontent/uploads/2013/04/eatart-mag-tim-v9-3.jpg. 21 47 materials and components. While Solar Sinter is more successful as a tool than Jansen's Strandbeest, some meaning is lost due to the aesthetics of the machine overshadowing the poetic narrative. Photo of Markus Kayser's Solar Sinter Project 22 Markus Kayser, Solar Sinter, 2011, http://www.markuskayser.com/files/gimgs/22_solarsiterO 1 10.jpg. 22 48 An artistic artifact produced by Markus Kayser's Solar Sinter 23. Hehe is a collaboration between Helen Evans and Heiko Hansen that behaves as a research organization. Their aim is to address "people's undesired needs: health, security, communication, energy and the environment" 24 . Their use of ecological visualizations shows how a largely-ignored and environmentally hazardous every-day occurrence can be highlighted through public forms. In "Nuage Vert" (figure 6 below), the outline of an emissions cloud from a coal power plant is highlighted with a powerful green laser. In addition to being a powerful symbol, the project was also a social process. Hehe engaged the owners of the power-plant, as well as their customers. By gaining access to real-time user data, the size of the laser image on the cloud could be enlarged or contracted based on the amount of energy being used at any given time. When the local residents decreased their power consumption, the green visualization would grow larger as if power was being diverted to its projection. The artists were deliberately ambiguous as to where blame should be placed for the creation of the green house gasses and pollutants. Rather than preach, they allowed the material and aesthetic dimensions of the work to encourage a discourse on the subject of energy. 23 24 Ibid. Hehe, "About Hehe," 2013, http://hehe.org.free.fr/hehe/contact/. 49 Nuage Vert by Hehe - an ecological visualization 25 . Another example of the materialization of energy awareness is Mary Mattingly's "Flock House Project." Flock Houses are a group of ecologically-aware transient and public dwellings. Their deployment was choreographed throughout New York City in "three planes of living (subterranean, ground, and sky)". The process of their creation was collaborative and community oriented. By combining reused materials and industrial atrophy, Mattingly aims to promote the adoption of natural systems and renewable energy technologies. The presence of Flock Houses provokes discussion about current human displacement and catastrophe. By organizing workshops and interactive events, Mattingly's work enhances community-resourcefulness and learning while inspiring curiosity and creative exploration. The tensions between progressive city-dwelling environmentalists and the seemingly insatiable urban demand for energy and resources are highlighted through Mattingly's work. Rather than framing the discussion around negativity and protest, the installations are effective at highlighting the positive aspects of community resilience through amalgamation of ingenuity, technology and natural systems. The narrative surrounding these sustainable and natural systems are largely fictional. However, they successfully act as caravans of hope in the ecological journey that would otherwise seem to have an unavoidable and disastrous ending. 25 Hehe, Nuage Vert - Ivry 2010, Industrial environment, laser light, 2010, http://hehe.org.free.fr/hehe/NV10/index.html. 50 Mary Mattignly's Flock House Project 2 6. Anna Gartforth is able to transform the aesthetics of nature into forms that force us to consider the context of their existence. "Wandering Territory" contrasts the industrial imagery mirrored on the exterior of the polar bear with the curious animal's natural habitat. It successfully draws attention to the industrial perversion of natural environments and evokes a sense of technological loneliness. Gartforth's work is accessible and disarming in that it employs craft with common materials. Unlike the works of Kayser and Hehe, there is no implied hypocrisy since Gartforth successfully avoids energy intensive materials that one might associate with hightech components. Mary Mattingly, Flock House, Metal, fabric, plants, 2012, http://www.marymattingly.com/Default.html. 26 51 Anna Garforth's "Wandering Territory"27 . As a direct approach to energy driven processes, Kitty Kraus created a time-based sculpture composed of a incandescent light bulb surrounded by ink and embedded in ice. When the bulb was turned on, the ice was allowed to melt and thus an ink stain would remain on the gallery floor at steady state. The 2006 piece, "Untitled" serves as a minimalistic embodiment of what we fear about the future; After the lights go out and the ice has melted, our diminished view might be dominated by a large black stain. Kraus' presumably deliberate use of ambiguity is also why her work fails to provoke real change. It is easy to interpret this work as nothing more than an autonomous painting device. Garforth, Wandering Territory,2013, http://www.annagarforth.co.uk/work/wanderingterritory.html. 27 52 "Untitled" by Kitty Kraus 28 . Conclusion Existing works of art do exist in the region that lies between art and energy. However, it remains unclear what the broader impacts of these works are. How can we measure impact? Is it problematic to investigate art through measureable impacts? What are the consequences of developing clear goals in the pursuit of artistic research? I intend to treat this body of work as an exploratory and creative endeavor, while strongly adhering to scientific principals. My methodology is grounded in the belief that art can help answer difficult questions about anthropogenic existential risks such as Global Warming. My aim with this methodology is to travel to the fertile and relatively unexplored valley that lies between mountains of fears, predictions of the future and the mistakes of my predecessors. I aspire to have my own projects, Local Warming in particular, to serve as a creative tool that helps bring a sense of awareness about how we interact with energy related technologies that I hope will be part of the solution to our long term anthropogenic existential risks. Kitty Kraus, Untitled, lamp, ice, ink, plexiglas, 2006, http://www.galerieneu.net/artists/show/id/8. 28 53 Credits Readers: John May, Assistant Professor of Architecture , MIT Kate Armstrong, Director, Sim Centre, Emily Carr University Supporters: Kara Henderson, My infinitely supportive and patient partner in life Paul and Louise Christie, My parents MIT Senseable City Lab Lab Leadership: Carlo Ratti - director Assaf Biderman - associate director Yaniv Jacob Turgeman - research lead Rex Britter - environmental advisor Local Warming Project Team: Miriam Roure - project lead Matthew Claudel - curator Carlos Graeves - electrical engineer Saverio Panata - architect Matthias Danzmayr - software lead Jacob Fenwick - hacker/coder Shan He - Visualizations Pierrick Thebault - Visualizations Fabrication, assembly and design assistance: Ricardo Alvarez, Thomas Altmann, Dorothy Bassett, Clara Cibrario Assereto, David Dowling, Feifei Feng, Sebastian Grauwin, Chris Green, Elyud Ismail, Sam Judd, Aaron Nevin, Jessica Marcus, Oleguer Sagarra Pascual, Kristopher Swick, Michael Szell, Remi Tachet des Combes, Gean "Computer Builder" MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab Dina Katabi - director Deepak Vasisht - motion tracking designer Jue Wang - motion tracking designer MIT UROPs Thomas A Altmann, Elyud Ismail, Alan E Casallas, Brian Alvarez, Antonio N Rivera, Aurimas Bukauskas, Bradley Eckert, Chennah P Heroor, Chris Cook, Dana Gretton, Jamie L Voros, Jorrie M Brettin, Mike Klinker, John Mofor, Mosa Issachar, Nikolas Albarran, Oleksandr Chaykovskyy, Sam Judd, Alexander, Alexander D Campillanos, Gracie Fang, Kristopher Swick, Jacob Tims, Damien W Martin. 54 Bibliography Beck, Ulrich. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London [u.a.]: Sage, 2007. Bostrom, Nick. "Existential Risks: Analyzing Human Extinction Scenarios and Related Hazards." Journalof Evolution and Technology, Vol. 9, No. 1 (2002). http://www.nickbostrom.com/existential/risks.html. Burn, Adam. SHield World Construction.Digital, February 26, 2009. http://adamburn.daportfolio.com/gallery/124232#10. Dyson, Freeman. Selected Papersof Freeman Dyson: With Commentary. USA: American Mathematical Soc., 1996. "Evolution and General Intelligence: Three Hypotheses on the Evolution of General Intelligence." Scientific American (October 30, 1998). https://www.csulb.edu/-kmacd/3461Q.html. Freitas Jr., Robert A. "A Self-Reproducing Interstellar Probe." A Self-Reproducing Interstellar Probe, 1980. http://www.rfreitas.com/Astro/ReprojBlSjuly1980.htm. Fuller, R. Buckminster, Snyder, Jaime. OperatingManualforSpaceship Earth. Baden, Switzerland: Lars Muller Publishers, 2008. Galison, Peter, Gerald James Holton, and S. S Schweber. Einsteinfor the 21st Century: His Legacy in Science, Art, and Modern Culture. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008. Garforth. Wandering Territory, 2013. http://www.annagarforth.co.uk/work/wanderingterritory.html. Gere, Charlie. Art, Time, and Technology. Oxford; New York: Berg, 2006. Grey, Alex. "Alex Grey." Alex Grey. Accessed May 7, 2013. http://alexgrey.com/. Psychic Energy System. Acrylic on linen, 1980. http://alexgrey.com/art/paintings/sacred-mirrors/psychic-energy-system/. Harris, Marvin. Cannibalsand Kings: Originsof Cultures.Toronto, ON: Vintage, 1991. Hehe. "About Hehe," 2013. http://hehe.org.free.fr/hehe/contact/. Nuage Vert - Ivry 2010. Industrial environment, laser light, 2010. http://hehe.org.free.fr/hehe/NV10/index.html. Jansen, Theo. Strandbeest.Plastic, fabric, 2012. http://eatart.org/wpcontent/uploads/20 13/04/eatart-mag-tim-v9-3.jpg. Jevons, William. Coal Question. 3 Reprint. Cambridge, England: Augustus M Kelley Pubs, 1906. Kardashev, Nikolai S. "On the Inevitability and the Possible Structures of Supercivilizations." In The Searchfor ExtraterrestrialLife: Recent Developments, edited by Michael D. Papagiannis, 497-504. International Astronomical Union 112. Springer Netherlands, 1985. http://ink.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-009-5462-5_65. Kayser, Markus. Solar Sin ter, 2011. http://www.markuskayser.com/files/gimgs/22_solarsiterO110.jpg. Klugman, Jeni. "The Real Wealth of Nations: Pathways to Human Development." Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. Kraus, Kitty. Untitled. Lamp, ice, ink, plexiglas, 2006. http://www.galerieneu.net/artists/show/id/8. Lovelock, James. "New Scientist," February 6, 1975. Lutz, Wolfgang, Warren C. Sanderson, and Sergei Serbov. The End of World Population Growth in the 21st Century: New ChallengesforHuman CapitalFormationand Sustainable Development. Earthscan, 2004. 55 Malthus, Thomas Robert. An Essay on the Principleof Population:Or, A View of Its Pastand PresentEffects on Human Happiness.London, England: Printed for J. Johnson, by T. Bensley, 1807. Mattingly, Mary. Flock House. Metal, fabric, plants, 2012. http://www.marymattingly.com/Default.html. Nisbet, Robert A. History of the Idea of Progress.New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1980. Perryman, Michael. "The Origin of the Solar System." arXiv:1111.1286 (November 5, 2011). http://arxiv.org/abs/1111.1286. Postman, Neil. Technopoly: The Surrenderof Culture to Technology. New York, NY: Knopf, 1992. Revkin, Andrew C. "Confronting the 'Anthropocene'." Dot Earth Blog. Accessed December 3, 2013. http://dotearth.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/05/11/confronting-theanthropocene/. Ristinen, Robert A., and Jack P. Kraushaar. Energy and the Environment.2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2005. "United Nations Millennium Development Goals." Accessed May 11, 2013. http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/environ.shtml. Wilson, Stephen. InformationArts: IntersectionsofArt, Science, and Technology. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2002. Your Monsters -- Why We Must Care for Our Technologies As We Do Our Children," accessed December 23, 2013, http://thebreakthrough.org/index.php/journal/past-issues/issue-2/love-yourmonsters/. u Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern (Harvard University Press, 2012). P 17 'i Ibid., 18. I "Love iv Ibid. V"WMO Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion," 2010, http://acdbext.gsfc.nasa.gov/Documents/03_Assessments/#WM02010. vi Latour, We Have Never Been Modern, 6. vii "Love Your Monsters -- Why We Must Care for Our Technologies As We Do Our Children." viii "Love Your Monsters -- Why We Must Care for Our Technologies As We Do Our Children." ix Ibid., 7. x Bruno Latour, "Why Has Critique Run Out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern," CriticalInquiry 30, no. 2 (January 2004): 227, doi:10.1086/421123. Ibid., 226. xi Ibid., 227. xiii Bruno Latour, Pandora'sHope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies (Cambridge, xii Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999), 3. Ibid., 22. xv Ibid., 9. xvi Ibid., 10. xiv 56