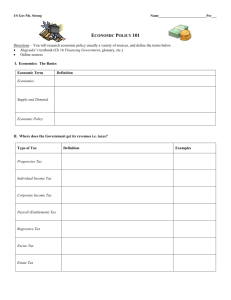

THE REDISTRIBUTIVE IMPACT OF GOVERNMENT SPENDING

advertisement