Payment System Regulation for Improving Financial Inclusion Maria Chiara Malaguti

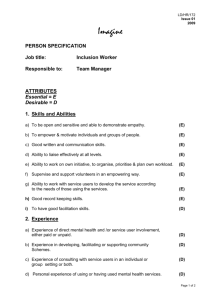

advertisement