A COLLECTIVE BIOGRAPHY OF THE FOUNDERS OF THE AMERICAN A DISSERTATION

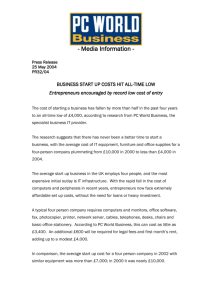

advertisement