AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF

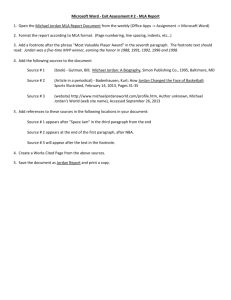

advertisement