Effects of Harmful Environmental Events on Reputations of Firms

advertisement

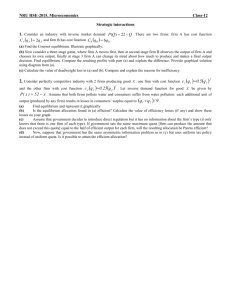

1 Effects of Harmful Environmental Events on Reputations of Firms* Kari Jones Department of Economics Emory University Atlanta, GA 30322-2240 email: kjone01@emory.edu Paul H. Rubin Department of Economics Emory University Atlanta, GA 30322-2240 email: prubin@emory.edu Abstract: Many previous event studies have found unexpectedly large losses to firms involved in negative incidents. Many of these studies’authors explain such losses as “goodwill losses” or "reputation effects." To test this hypothesis, we search for residual losses (in excess of direct costs) to firms involved in events which produce ill will, but do not affect the quality of their final products nor break implicit labor or supply contracts. We find an overall insignificant capital market response to a sample of 98 negative environmental events (representing all such incidents reported in the Wall Street Journal between 1970 and 1992 in which electric power companies or oil firms with listed stocks were involved). Although others have found similar outcomes for more limited samples, our results enhance previous research by extending similar findings to a broader range of environmental incidents over a longer time period. Further, our findings suggest that the large residual losses of other studies may be due to reputation (and not measurement errors or event study idiosyncrasies), but only when the notion of "reputation effects" is limited to punishment solely by those who are directly harmed by the firms' conduct. * We would like to thank Owen Beelders, Robert Carpenter, Joel Schrag, and Susan Griffin for providing helpful suggestions and comments. Additionally, we thank Xiaolan Wang of the Emory University Goizueta Business School for carefully, quickly, and patiently fulfilling our requests for CRSP data. Errors and omissions are attributable solely to the authors. 2 INTRODUCTION Empirically, researchers have found large unexplained capital market losses to firms involved in “negative” incidents. Implicitly and explicitly many authors attribute these residual losses to attrition of reputational capital, often for lack of another explanation. Theoretical models of reputation describe retaliation or punishment by a firm’s contractual partners when the firm deviates from: an implicit agreement on quality of its product (by consumers); a profitmaximizing strategy (by shareholders); an implicit labor contract (by employees); or an implicit purchasing agreement (by suppliers). However, some of the authors of the original event studies (and those commenting on them) also imply that reputation may include punishment by the firm’s contractual partners for harm done to others. Mainstream theoretical models of reputational mechanisms do not predict that one group will punish when another group is harmed. (Unless the group doing the punishing expects a positive probability of being harmed if the firm’s devious behavior continues, punishment requires that the harmed group’s well being enter the punishing group’s utility functions.) The factors driving the unexpected results of previous event studies are yet to be explained. Policy decisions and academic questions depend on correctly identifying the situations in which reputational mechanisms are present. This paper provides evidence that reputational mechanisms are a plausible explanation of the unexplained residual losses, when reputation is defined traditionally – that is, only those who are (potentially) harmed incur the costs of punishment. 3 The paper is organized as follows: Section I contains an overview of previous event studies that relate to the question of reputation effects. Section II includes an explanation of these past results within the traditional models of reputation and reviews examples from the academic literature and popular press of the widespread assumption that a firm’s social reputation affects its capital market value. We outline an empirical test of this assertion. Section IV includes a discussion of the empirical procedure and the data. Finally, Section V presents the empirical results and conclusions. I. UNEXPLAINED PAST EMPIRICAL FINDINGS Unexplained losses have been found in a variety of previous event studies1 designed to measure the effect (and effectiveness) of regulation on a firm or industry2, and more recently, the effect of an even wider variety of nonregulatory events. Among the regulatory event studies, significant capital market losses are associated with firms’involvement in Federal Trade Commission censures for false and deceptive advertising (Peltzman (1981) and Mathios and Plummer (1989)), government-ordered drug, automobile, and other product recalls (Jarrell and Peltzman (1985), Hoffer, et al. (1988), Rubin, et al. (1988), and Bosch and Lee (1994)), other product-safety-related regulatory (and private) actions (Viscusi and Hersch (1990)), Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) violations (Hersch (1991)), Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) violations (Davidson, et al. (1989) and Fry and Lee (1989)), and corporate crimes such as fraud and price fixing (Cloninger, et al. (1988), Karpoff and Lott (1993), and Reichert, et al. (1996)). 1 2 Section IV contains an overview of the methodology for readers unfamiliar with the procedure. See Schwert (1981) for an overview 4 Nonregulatory events also lead to large and often unexplained losses. These include the changing of a product’s formula (Benjamin and Mitchell, undated manuscript), the Tylenol poisonings (Mitchell (1989) and Dowdell, et al. (1992)), and airline crashes (Mitchell and Maloney (1989) and Chalk (1987)). While these studies show the negative effects of a bad reputation, one study provides evidence that good reputations can increase a firm’s value. Chauvin and Guthrie (1994) found that firms experienced a statistically significant average gain in market value from appearing on Working Mother magazine’s list of “best” employers. In most of these studies the monetary losses to stockholders are shown to significantly outweigh the direct and estimated indirect costs of the incidents. These results are surprising to many authors. Peltzman (1981) characterized his findings as “amazing” and “… a mystery” (at 418), while Rubin, et al. (1988) label their extremely significant findings “surprisingly large” (at 37). For lack of a better explanation many authors characterize the residual losses (above and beyond explainable costs) as losses of reputation or goodwill. Dowdell, et al. (1992), Jarrell and Peltzman (1985), and Rubin, et al (1988) characterized the excess losses in their studies as losses of a firm’s goodwill. Mitchell and Maloney (1989) dubbed their residual losses a “brand name effect”. Previous event studies involving environmental events show mixed results. Muoghalu, et al. (1990) found that in hazardous waste lawsuits that allege damages from improper hazardous waste disposal, defendant firms suffered significant losses. However, Harper and Adams (1996) found that the average market reaction of a firm’s stock upon being named a potentially liable party in a Superfund cleanup effort was not significantly different from zero. Laplante and Lanoie (1994) found that for negative environmental events reported in the media, Canadianowned firms did not experience significant declines in stock market value either when an 5 environmental violation was announced or when a lawsuit was filed. This is consistent with the small average penalty paid. The authors found that significant market adjustment occurred only after a suit settlement was announced. It is not known if the firms experienced residual losses. Karpoff, Lott, and Rankine (1998) found a statistically significant average loss of 0.85 percent to firms involved in negative environmental incidents. The average loss was greater for events where initial press reports of the incident occurred either at the allegation date or the date charges were filed. However, when comparing these figures with the direct costs of the incidents, the authors found no evidence that any part of this loss could be attributed to reputation effects. Hamilton (1995) investigated the stock market effects of information releases concerning a firm’s pollution activities. Manufacturing facilities must report annual releases of chemicals to the EPA. This information is relayed to the public in a database called the Toxics Releases Inventory (TRI). Hamilton studied both how the media treated TRI information and what affects it had on stock prices of polluting firms. He found that on the day of the information release, firms suffered, on average, a statistically significant drop in capital market value. This loss was higher the greater the number of chemicals per facility. Capital market losses were also positively correlated with number of Superfund sites. Hamilton’s explanatory regressions suggested that potential liability and other direct monetary exposure issues, rather than consumer forces, drove these losses. Finally, Blacconiere and Patten (1994) reported that Union Carbide took a 27.9 percent, or approximately $1 billion, hit from the Bhopal chemical leak, while its industry rivals suffered an average 1.28 percent loss in capital market value. The authors attributed these losses to investors’revisions of possible production-side risks and increased regulatory exposure. A summary of these event studies is presented in Table 1. 6 II. EXPLAINING PAST EMPIRICAL RESULTS Traditional Theories of Reputation Some of the studies reviewed in Section I attempt to explain their estimated capital market losses by regressing them on study-specific potential explanatory factors. Others offer ad hoc explanations of possible factors affecting the magnitude of losses. However, none attempts to formally model the reputational mechanism at work when the authors refer to “reputation effects”. Traditional theories of reputational mechanisms have their roots in the concepts that are articulated in Akerlof (1970), Klein, Crawford, and Alchian (1978), Klein and Leffler (1981), Nelson (1970), and Nelson (1974), and are modeled formally in Shapiro (1983). Akerlof (1970) notes that in some situations of asymmetric information between buyers and sellers, mutually beneficial trades may be precluded by the prospects of cheating. Subsequently, economists began describing and modeling the methods that have evolved in such markets to mitigate3 this problem. In particular, firms often use reputation to guarantee product quality. Klein, et al. (1978) first suggested that potential cheaters might offer a forfeitable hostage to guarantee performance in interfirm contracting. Klein and Leffler (1981) applied this concept to the consumer-producer relationship. High prices signal high quality, but consumers pay these prices only if they receive some guarantee of high quality. Producers of high quality goods make firm-specific investments that are forfeited if consumers discontinue purchases of the firm’s output. Consumers realize that firms are unlikely to deviate from high quality because continued high quality production allows them to recoup their investments in “hostages”4. 3 As Shapiro (1982) notes, full-information quality levels are unattainable even with a reputation mechanism. Other investigations into the nature of the outcomes of various reputation mechanisms are found in the signaling models of game theorists. See, for example, Allen (1984), Kreps and Wilson (1982), Milgrom and Roberts (1986), and Kihlstrom and Riordan (1984). 4 7 Thus, if a firm deviates from a quality commitment (or even if an incident occurs that signals without one-hundred-percent certainty that the firm has deviated), customers punish the firm by lowering their willingness to pay. The net present value of the future profit stream declines and the capital market value of the firm falls.5 These notions of stochastic and nonstochastic signals of deviations from prior commitments can be generalized to include the firm’s reputation with its other contractual partners, namely its employees and suppliers. If a firm cheats in some way on a commitment it has to a supplier, the firm is likely to incur higher input costs in the future. Firms that cheat their employees may face wage premiums to attract future workers in a competitive labor market. Finally, firms also have reputations with investors. A firm’s involvement in a negative incident may lead investors to reevaluate their faith that the firm’s management will steer clear of such costly events in the future. Investors may also revise their subjective probabilities of tighter future regulatory scrutiny or additional regulations. The higher the perceived risk of such consequences, the lower the firm’s expected future profit stream, and the lower the share price. In summary, the comments concerning the findings of previous event studies, framed in the theory of reputation, suggest that “reputation effects” are transmitted several ways. (1) The incident may result in a downgrading of the firm’s reputation with its customers, employees, or suppliers. Depending on the nature of the implicit commitment, this loss of reputation may result from (a) a deviation from expected behavior (in a nonstochastic setting), or (b) consumers’, employees’, or suppliers’revision of their estimates of the probability that the firm has cheated (in a stochastic setting). 5 Ippolito (1992) reported in a study of the mutual fund market that consumers rationally react in this manner, thus preventing a “lemons” market. 8 (2) The firm also may suffer capital market losses if the event leads to decreased faith in the firm’s management on the part of investors. This may be the result of (a) perceived increased risk of future incidents, and/or perceived increased regulatory exposure. While these reputational factors are reasonable partial explanations of observed residual losses, they are incomplete interpretations for at least two reasons. First, no empirical evidence exists to show that a combination of (1) direct costs, (2) consumers’response to deviations from expected product quality, (3) employees’response to deviations from implicit employment contracts, (4) suppliers’reactions to deviations from implicit purchasing agreements, and (5) investors’decreased faith in management explain all of the losses reported in empirical studies. In fact, both Peltzman’s work, (1981) and Peltzman’s and others’comments suggest otherwise. Second, suggestions of the importance of social reputation in explaining these residual losses are pervasive in the literature. That is, it is widely suggested that the firms’contractual partners punish firms for harm done to others. Without a unified model of reputation (consistent with the stylized facts), the social reputation hypotheses, while not compatible with economic theory, continues to carry as much weight as the other ad hoc explanations of residual losses. The (Conjectured) Social Component of Reputation The foundations of the case for social reputation are found in suggestions and anecdotes in the literature and also in the results of experimental economics. Many of the original event studies’authors suggest that a firm’s social reputation can affect sales6. Some quotes are more direct. Hersch (1991) suggests that in the aftermath of an EEO violation “costs include … 6 In contrast, Karpoff and Lott (1993) find that firms that are penalized for committing frauds that do not affect consumers, suppliers, or stockholders (such as paperwork errors) suffer no unexplainable stock market losses. 9 adverse publicity that might result in the loss of sales … ” (at 140). Muoghalu, et al. (1990), in reference to residual losses suffered by firms involved in Superfund cases, state that “stockholder losses … include … public ill-will resulting from the lawsuit or the dumping” (at 358, note 5). Hanka (1992) noted that “image-conscious firms fear the reputation consequences of pollution” (at 26). Davidson, et al. (1994) attribute some of the significant losses subsequent to OSHA violations to “negative publicity for the firm”. These comments suggest that consumers, employees, or suppliers7 punish firms for engaging in practices that are “socially irresponsible”. The losses suffered from this type of retaliation would be in addition to other direct and indirect costs of the incident, including the reputational losses for failing to honor implicit contracts with consumers, employees, or suppliers, and any losses from decreased faith in management. Thus, such punishments would create the unexplained “goodwill” or “reputation” effects. These types of comments cover not only the negative effects of a bad reputation, but also the positive effects of a good social reputation. Chauvin and Guthrie (1994) state “… if investors believe that customers will prefer purchasing goods and services from ‘good’employers, [the positive returns to firms on Working Mother’s “best employer” list] may also reflect estimates of the effect that labor market reputation may have on sales” (at 551). Schwartz (1968) states that “(g)ifts which enhance the public image of a corporation can advantageously shift the demand curve for the corporation’s product” (at 480). Navarro (1988) concluded that giving to charity increases demand or decreases demand elasticity for a firm’s product(s). Analogously, the 7 While socially conscious investors may divest themselves of the stock of firms they consider irresponsible, this phenomenon is unlikely to affect the observed stock market loss. Assuming an efficient market, the investors interested only in risk and return will bid against each other for the divested shares until the price reflects the value of the firm. 10 tarnishing of a firm’s image could decrease demand or increase demand elasticity for a firm’s product(s). Making the “social reputation” case even stronger is the anecdotal evidence that suggests that customers gain utility and disutility from characteristics of firms’production and financing processes. Consumers readily purchase recycled products (such as notebook paper and paper towels) which function no better than nonrecycled paper products, yet command price premiums. Investors put money in socially conscious mutual funds that pay lower returns for the risk than their socially-disinterested counterparts. Rothchild (1996) states that “[o]ver the past 12 months, the 39 ethical funds tracked by Lipper [Analytical] have returned 18.2% vs. 27.2% for the S&P 500” (at 197). Rogers (1996) translates this into a $57.5 billion price investors were willing to pay to avoid investing in undesirable firms over the year. Extra-legal social enforcement mechanisms exist to enforce a wide variety of desired behaviors – both economic and social. One example is boycotts. Consumer groups boycott producers, and often successfully change producer actions. A November 8, 1990 Wall Street Journal article reports that at least 300 boycotts of producer policies occurred in 1991 alone. The authors report that “facing embarrassing publicity, many companies have changed their policies to pacify the boycotters”8. The article further reports that, according to a consumer poll in June 1991, 27% of consumers boycotted a product because of a manufacturer’s record on the environment. Talk is cheap, but firms’actions, based on such beliefs, are not. Causal observation of business practices such as voluntary divestiture from South Africa, advertisements touting a firm’s expenditures on the environment or “fairness” in hiring practices, appointment of environmentalists to boards of directors, and emphasis in stockholder reports on politically 11 correct firm policies suggest that firms reap some reward from consumer or investor knowledge of these practices. Arguably, such practices do not improve the efficiency of the actual production process, but, because they are common practice, firms must expect that they add to profits. A spokesman for Reebok International Ltd. claims “[m]ore and more in the marketplace, … who you are and what you stand for is as important as the quality of the product you sell” (Hayes and Pereira, 1990, at B1). Adding to the fervor of these suggestions of social reputation are experimental economists’ reports of evidence of widespread principle-based behavior in laboratory tests9 and behavioral models in the literature which are generated to be compatible with these experimental results10. III. TESTING FOR EVIDENCE OF A SOCIAL REPUTATION EFFECT Both the formal definitions of reputation in the literature (see, for example Shapiro (1982)) and the formal discussions in the above event studies assert that “reputation effects” refer only to the reputation of a firm’s output in the goods market, its reputation for its dealings with its employees or suppliers, and its management’s reputation in the capital market11. However, the informal discussion suggests that social reputation affects profit. These assertions have significant consequences. Voters, regulators, and taxpayers make assumptions concerning retaliatory behavior trends when voting for (or otherwise affecting) government involvement in markets. 8 For example, Karpoff, et al. (1998) note that the U.S. Sentencing Commission is Hayes and Pereira (1990) See, for example, Camerer and Thaler (1995) and Kahneman, et al. (1986) in which players are willing to sacrifice money to reward players who are kind to others in previous rounds and punish those who were previously unfair to their opponents. 10 See, for example, Bolton (1991) in which relative payoffs matter and Rabin (1993) which allows for agents to reward those who are kind and punish those who are unkind. 11 Chauvin and Guthrie (1994) note that “… in all theoretical work on reputations, reputations have economic value because they improve the efficiency of markets… ” (at 546). Schwartz (1968) notes that “(h)istorically, economists have tended to ignore private philanthropic behavior and to regard it as economically irrational” (at 479). 9 12 explicitly considering the existence of reputational effects from environmental incidents in setting its sentencing guidelines for corporate environmental crimes. The goal of the empirical section of this paper is to test whether, as copious comments suggest, social reputations are a factor in the unexplained losses of previous event studies. Our procedure is to test for residual losses to firms involved in negative events that do not harm the firm’s contractual partners (except through direct losses from the incident), but do affect their social reputation by harming third-parties. Negative environmental incidents represent such events. We employ standard event study methodology to determine the effect that a negative environmental event has on the market value of a firm. Under an assumption of efficient markets, capital market participants produce an unbiased estimate of the value of a firm reflecting all available information. A firm’s abnormal return12 immediately following the release of news concerning the firm is the market’s unbiased estimate of the costs (or benefits) of the news. Thus, we calculate and analyze abnormal returns to firms involved in negative environmental incidents. Absence of residual losses suggests that agents do not punish firms for harm done to others, while presence of significant residual losses suggests that measurable reputation effects may result from deterioration of social reputation. If residual losses to such events are found, it will remain to be shown that these losses represent punishment for social reputation, and not, for example, a measurement problem common to all event studies. As such, we conjecture that consumers’propensities to punish decrease as the cost of punishment increases, but a measurement error or other extraneous factor should not vary with costs of punishment. Therefore, we prepare to test any residual losses for social reputation effects by collecting a 13 sample of environmental mishaps caused by electric power companies and oil companies. The utilities represent an industry with few substitutes (where punishment would be expensive and, therefore, less likely), while the oil companies represent an industry with many close substitutes (where punishment would be relatively cheaper, and, thus, more likely). Finally, we perform a cross-sectional analysis of the observed abnormal returns. IV. THE EMPIRICAL MODEL AND PROCEDURE The Event Study Data and Methodology13 A list of potential events was drawn from all negative environmental events suffered by oil concerns and electric utilities between 197014 and 199215 as reported in The Wall Street Journal Index. Potential events had to meet three criteria. First, the event must have had a negative environmental impact as the result of the actions of an oil division or electric power producing division of the firm. This is because, if consumers were distressed upon hearing of pollution by Acme Chemical, but were unaware that Acme was a subsidiary of ABC Oil Co., they would be unable to punish, if they were so inclined. Second, the event must not have affected the quality of the firm’s physical product. For example, some oil firms have been charged with switching leaded and unleaded fuel. Using the wrong type of fuel not only causes pollution, but also inflicts costly damage to a car’s engine and exhaust system. In such cases, consumers’material self-interest would lead to decreased demand; retaliation for any resulting pollution could not be separated16. Third, because all of our stock returns data are from the CRSP tapes17, the target 12 defined as the difference between the firm’s observed return and its expected return For a “how-to” guide of event study particulars, see Armitage (1995) and Peterson (1989). 14 The environmental movement was gathering steam and the EPA was created this year. 15 Environmental fervor seems to be related to political climate and this year ended a presidential administration. 16 Most event studies also exclude any events that had other news about the firm reported in the event window, because the effects of such news are inextricably summed with the effects of the event of interest. Because large oil 13 14 firm’s returns must be available on the CRSP tapes for the entire estimation period and event window. We use as our event date, the day that news of the event appears in the Wall Street Journal (WSJ), unless the report suggests a more appropriate date. When picking our event dates, we carefully considered the fact that if WSJ announcement dates are used as event dates when they do not correspond to the date of the precipitating incident, the market may have adjusted to news of the incident before the event date, consequently biasing announcement date losses downward. The information to which market participants are most likely to react is not always the precipitating incident. The market reaction to an announcement of an investigation that has a 5% chance of resulting in a $1M fine will be much different that the reaction to the commencement of an investigation that has a 95% probability of resulting in a $1M fine. The best option is to use the date most likely to contain the bulk of the market adjustment to the “event”. If the event were of the former type, this would be at the time of the precipitating incident. If the event were of the latter type, this would be at the time that news that an actual loss will occur (or, possibly, is more likely) reaches the market. The WSJ announcement date is the appropriate event date for our study for three reasons. First, there is precedent for using this methodology. Many event studies have used the WSJ announcement date as the event date. Secondly, most of the other studies with which we are comparing our results employ this methodology. To allow meaningful comparisons of our results with past studies’results, we follow comparable procedures. The third reason is that we feel the WSJ gets it right most of the time. That is, the Journal’s report of news that affects the firms are mentioned in the financial news on an almost-daily basis, we left all events with concurrent news in the sample to get as much information as possible. However, we calculated the results for various subsets of events, depending on the nature of the concurrent news. 15 market is reasonably accurate and timely. At a minimum, there is enough uncertainty left when the WSJ publishes a news story that the information is still novel. Helmuth, et al. (1994) found significant market reaction to corrections printed in the WSJ. Firms realized significantly positive returns on the day that corrections representing “good news” were reported, and suffered significant losses when corrections representing “bad news” were printed. Further, there was no post-event rebound of value. As the authors note, these results imply that the “corrections are at least partially unanticipated by the market” suggesting “that a subset of market participants depend on the WSJ for financial information.” The results of previous event studies (particularly previous environmental event studies), and the seemingly-random actions of the EPA and environmental groups, suggest that being implicated in an environmental incident often is associated with a low probability of further action or concern. Karpoff, Lott, and Rankine (1998), at 25, conclude that penalties stemming from environmental incidents are highly variable and not easy to predict. Thus, news of many potential events is unlikely to be printed until some official action is taken. However, some events (e.g. Valdez and Three-Mile Island) seem highly likely to generate further costs (and, thus, were reported very close to the precipitating incident date)18. The final sample of 98 events is summarized in Table A-1 of the appendix. Included are the name of the firm, a description of the event, the date that news of the event first appeared in the Wall Street Journal, and any other firm-specific news reported in the Journal on the days surrounding the event. 17 The CRSP tapes are a database of stock prices and other securities information administered by the Center for Research in Stock Prices at the University of Chicago. 18 Additionally, to test for upward bias of abnormal returns resulting from late reports of important stories, we control for the timeliness of the report in our explanatory regression of these returns. 16 Our goal is to identify the firms’abnormal returns from these negative environmental incidents. The abnormal return to a firm from the event is the difference between the firm’s actual return and the return we would expect for the firm in the absence of the incident. We employ the market model to obtain parameters for generating expected returns. Specifically, for each event, using returns for days just prior to the event date, we obtain an OLS estimate of: RETit = α i + β i MRETt + eit where RETit ≡ the percentage return to the target firm of event i at date t, MRETt ≡ the percentage return at time t to the NYSE/AMEX value-weighted portfolio, and eit is random disturbance to the event i target firm’s return at date t. For each event, the et are distributed with a mean of zero and standard deviation of σi2. Accordingly, α is a constant and β is the systematic risk of firm i’s stock over the estimation period (beta in the CAPM model). Time is indexed t, such that t=0 on the event date. The timespan used to estimate α and β is referred to as the estimation period. We calculate expected returns using the 199 days immediately prior to the event date. The resulting estimates of αi and βi, denoted ai and bi respectively, are used to calculate expected returns to the target firm of event i around the event date. The difference between the actual return on any day and the expected return calculated for that day (the prediction error) is the day’s abnormal return: ARit = RETit − (ai + bi MRETt ) where ARit is the abnormal return to the target firm of event i on day t. 17 The average abnormal return to the entire sample on any day t, denoted AARt, is the average of the abnormal returns on day t for each event in the sample: n AARt = ∑ i =1 ARit n , where n is the number of firms in the sample. The time span over which the market is assumed to fully adjust to news of the event is called the event window. The abnormal return to the firm accumulated over this adjustment period is our best estimate of losses (or gains) to the firm from the event19. This measure is called the cumulative abnormal return. For a given event window [e.g. the event window consisting of days t=-1 and t=0, denoted (-1,0)], the cumulative abnormal return for event i, denoted CARi, is defined as the sum of the abnormal returns for each day in the event window: b CARi = ∑ ARit , t =a where a ≡ the first day in i’s event window, and b ≡ the last day in i’s event window. For any given event window [e.g. the (-1,0) window], the average cumulative abnormal return to the full sample, ACAR, is the average over the sample of each CARi: 19 We assume that the market reacts immediately to news of the event. However, because it was unclear for many of our events whether this news reached the market before 4:00 p.m. on the day before it appeared in the Journal, we use the (-1,0) event window. For comparison, we also calculate results for the day t=-1, day t=0, day t=1, and the (-5,0), and (-1,9) windows. 18 n ACAR = ∑ CAR i i =1 n . For a given event window, the total monetary loss to the firm’s shareholders (in dollars) from the event is simply the product of the firm’s CAR and the value of the firm’s shares outstanding on the day t=-2. Cross-Sectional Analysis of the Event Study Results After we calculate the cumulative abnormal returns to each event, we investigate the factors contributing to these observed abnormal returns. The (-1,0) window CARs for all events are regressed on event-specific explanatory variables in an attempt to identify other causal factors that may explain the event study results. The first explanatory variable is report type. This is a proxy for how novel the news reported on the event date is to market participants. The second explanatory variable, action type, accounts for the possibility that different types of accusers impose different costs on polluters. The third explanatory variable is concurrent news. Events are categorized by type of concurrent news in the (-1,0,1) window. The concurrent news on day t=1 is included since this news may have reached the market on day t=0. Inclusion of the concurrent news variable will net out any biasing effects of other firm-specific news in the event window. The fourth explanatory variable is time. It may proxy for environmental consciousness and regulatory and/or prosecutorial fervor in the environmental sector. In an alternative specification we dummy for presidential administration. 19 The fifth explanatory variable is industry. Dummying by industry controls for the possibility that oil firms’and electric firms’reactions to new information are systematically different, either because the utilities are rate-of-return regulated, and/or because their stocks are traded more thinly, on average, than oil stocks. The sixth and final explanatory variable, firm size, controls for the possibility that extremely large firms’abnormal returns test insignificant because losses from the incident are dwarfed by the sheer magnitude of the firms’market values. The explanatory regression results are obtained by an OLS estimate of CARi = α + β1 REPORTC i + β 2 REPORTRi + δ1 ACTIONFi + δ2 ACTIONPi + δ3 ACTIONM i + τ1 NEWSG i + τ 2 NEWSBi + τ 3 NEWSN i + ηTIMEi + ϕ INDi + γ SIZEi + ei , where REPORTCi = 1 if first news of event i is reported at the time of the filing of the first suit, the first official allegation, the first official warning of an impending suit or charge, or a settlement concurrent with official charges, =0 otherwise. REPORTRi = 1 if first news of event i is an update on a present court case, a judge or jury ruling, a penalty ruling, or a settlement (not concurrent with the accusation), =0 otherwise. ACTIONFi =1 if event i involves only a federal action, =0 otherwise. ACTIONPi =1 if event i involves only a private action, =0 otherwise. ACTIONMi =1 if event i involves a multi-party action, =0 otherwise. NEWSGi =1 if other firm-specific news reported in event i’s (-1,0,1) window is expected to increase the firm’s value, =0 otherwise. NEWSBi =1 if other firm-specific news reported in event i’s (-1,0,1) window is expected to decrease the firm’s value, =0 otherwise. NEWSNi =1 if other firm-specific neutral news or news with an uncertain affect on the firm’s value is reported in event i’s (-1,0,1) window, =0 otherwise. TIMEi = the last two digits of the year of event i, INDi =1 if event i involves an oil firm, =0 if event i involves an electric utility, and SIZEi = the total dollar value of the firm i’s outstanding shares at t=-2, measured in thousands of 1987 dollars. 20 V. RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS Abnormal and Cumulative Abnormal Returns 20 The CARs for the (-1,0) window for each of the 98 events are presented in Table A-2 of the appendix, along with information concerning the costs of each event. A summary of the average abnormal returns (AARs) and the average cumulative abnormal returns (ACARs) for various windows is presented in Table 2. The split of negative and positive returns is not significantly different from what may occur randomly, and relatively few of the firms’stocks reacted significantly to news of the incident. When all events are considered, the ACAR to the full sample for the (-1,0) window is positive. Additionally, there are eight significantly positive CARs. These results are counterintuitive, because, even if reputation effects are not present, there are direct costs to the incidents. Four events for which the target firm had significantly positive abnormal returns on either day t=-1, day t=0, or in the (-1,0) window also had “good” firm-specific news in the event window (events 39, 59, 72, and 82). In addition, four more events (#18, 19, 20, and 21) shared an event date on which Mideast tensions threatened to delay a possible loosening of oil importing restrictions by President Nixon. Three of these CARs are significantly positive. Only one event with bad news in the window (#13) produced a significantly negative abnormal return on t=-1or t=0 or in the (-1,0) window. Removal of these nine (possibly biasing) events from the sample yields an insignificant 0.25 percent, or $882,000, average loss to the remainder of the sample. When the 34 events with any concurrent firm-specific news in the event window (good, 20 A subset of fourteen events was used to test the effect of different combinations of estimation period (150-day or 200-day) and market return calculation (equally-weighted or value-weighted) specifications on the predictive power of the market model. No one measure or class of measures produced a significantly higher correlation between targets’returns and market returns. The subsample was also used to determine whether either a procedure to net out 21 bad, or neutral) are excluded, the average cumulative abnormal return is an insignificant 0.016 percent gain21. These figures represent gross losses. Residual losses were not calculated since the ACAR is insignificant. That is, netting out the losses due to direct costs can only make an individual event’s return a larger (less negative) number. Thus the ACAR, net of direct costs, cannot be significantly lees than zero. In the full sample results, the t=-1 and t=0 windows show a significantly negative and a significantly positive AAR, respectively. However, this result appears to be driven by one unusual incident. Event 9 involves a radiation leak scare at a Rochester Gas and Electric plant only a few years after Three Mile Island. At first news of the incident (t=-1), a mass sell-off resulted in a 13.5 percent drop in the firm’s value. However, when more information was released the following day (t=0), the stock gained back almost nine percent (and the stock’s price was back to its pre-event level within five trading days). When event 9 is removed from the full sample (and each of our subsamples), the average returns in the t=-1 and t=0 windows are no longer significantly different from zero. With or without event 9, the ACAR for the (-1,0) window is insignificant, because the two days' reactions tend to cancel each other out. Insignificant average cumulative abnormal returns in the (-5,0) window and (-1,9) window suggest that the stock market’s adjustment to the event did not occur outside of the (-1,0) event window. The insignificant (-5,0) window suggests that news of the event did not reach the market just prior to the report date, while the insignificant (-1,9) window suggests that adjustment to the new news did not occur with a lag. the effects of industry-wide increased regulatory scrutiny or a procedure to net out the residual losses due to decreased faith in management was warranted for the full sample. Neither was found to be of significant benefit. 21 Additionally, when events 18 and 20 are removed, the (-1,0) ACAR is an insignificant 0.232 percent loss. 22 Explanatory Regression Results Our event study results suggest that abnormal returns to firms involved in negative environmental events are random and average approximately zero. Compared to event studies of other negative events that employ a similar methodology, we find a much smaller effect from negative environmental incidents. To test whether some causal variable(s) could explain the variation of CARs over the different firms and incidents, we regress the observed cumulative abnormal returns for the (-1,0) window on explanatory variables for report type, action type, concurrent news type, time, industry, and firm size. Consistent with our event study results, our explanatory regression results also suggest that abnormal returns to firms are random and can be explained as white noise. The adjusted R2 is 0.0605 and none of the regressors has explanatory power at a significance level of 0.20 or lower. The Durbin-Watson statistic is 1.8962 and a plot of the regression residuals appears normal. Two alternate specifications were tested. First, because categorizing type of news in the event window is a somewhat arbitrary choice on the part of the researcher, we test if the results are robust to classifying events as having either no news in the window or any news (good, bad, or neutral) in the window. In the second alternative specification, we dummy for presidential administration instead of employing the time variable. The alternative specifications also have very little explanatory power and yield intercept and slope coefficients that are not significant. The insignificance of the report type variables suggests that use of event dates postdating the initial incident date does not significantly bias the sample average cumulative abnormal return (ACAR) upward. This is accentuated by the fact that 70 events with first news at the time of the charge are being compared to only 18 events (including both the Valdez spill and Three Mile Island) with first news at the time of the precipitating incident. The insignificance of the 23 coefficient on the dummy for industry suggests that oil and electric firms do not have significantly different market reactions due to regulatory or thin-trading issues. Estimated intercepts and slope coefficients for each specification, along with corresponding t-statistics, are reported in Table 3. If, as some authors have suggested, there were a reputational penalty to negative environmental events, we would expect to find significantly negative residual losses in our study. Instead, the cumulative abnormal returns appear to be random. In keeping with the standard models of reputation, we find no evidence of a negative reputation effect. Our results are consistent with Harper and Adams’s (1996) finding that firms experienced insignificant changes in value upon being named a potentially responsible party in a Superfund cleanup. They are also consistent with Laplante and Lanoie’s (1994) finding that Canadian firms did not experience significant losses from announcements of environmental violations or lawsuits. Our results, however, extend this finding of insignificant22 market losses in environmental event studies to a broader class of regulatory as well as nonregulatory events. Our results are also consistent with the assertions and findings of Karpoff, et al. (1998) that formal penalties for committing environmental crimes are random and that stockholders realize this. Because our sample covers a period twice as long as Karpoff, et al.’s, (1970 through 1992 versus 1980 through 1991) we can be confident that their findings are not merely a figment of, for example, the “80’s mentality”, but span several decades and presidential administrations. 22 Muoghalu, et al. (1990) unsurprisingly found significant gross losses because they considered only a specific type of environmental incident that had (potentially large) direct costs. The authors did not report residual losses (net of direct costs), so reputation effects are not known. Hamilton (1995) found that firms suffered significant losses when information about chemical releases at their facilities was made public. However, in the author’s explanatory regressions, losses increased with number of chemicals at a facility but not with level of emissions, indicating potential future liability was more important than extent of current harm. Also, number of Superfund sites was 24 Conclusions We find an overall insignificant stock market response to a sample consisting of all negative environmental incidents (regulatory and nonregulatory) reported in the Wall Street Journal over the 1970 to 1992 period involving oil firms and electric power companies with listed stocks. Thus, our results suggest that other researchers’findings of insignificant reputation effects from regulatory environmental events extend to a wider class of regulatory and nonregulatory incidents than previously has been considered in the literature. These events affect firms' social reputations, but not the quality of their output or their reputations with employees or suppliers. Thus, our findings contradict the widely-asserted hypothesis that when firms develop negative social reputations (that is, negative reputations from harming third parties), their unaffected contractual partners will incur the costs of punishment. Rather, our findings affirm the traditional models of reputational mechanisms, which are effective when harms and punishments are limited to contractual partners. Moreover, our findings provide evidence that the large losses from harmful events are in fact due to stock market expectations that contractual partners will punish firms for imposing direct harms. associated with increased loss, but extent of media coverage had an insignificant effect, again indicating that response to potential risk exposure outweighed reactions to the firms’social reputation and goodwill. 25 BIBLIOGRAPHY Akerlof, George A., “The Market for ‘Lemons’: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1970, volume 84, pp. 488-500. Allen, Franklin, “Reputation and Product Quality,” Rand Journal of Economics, 1984, volume 15, pp. 311-327. Armitage, Seth, “Event Study Methods and Evidence on their Performance,” Journal of Economic Surveys, 1995, volume 8, pp. 25-52. Benjamin, Daniel K. and Mark L. Mitchell, “Commitment and Consumer Sovereignty: Classic Evidence from the Real Thing,” undated manuscript. Blacconiere, Walter G. and Dennis M. Patten, “Environmental Disclosures, Regulatory Costs, and Changes in Firm Value,” Journal of Accounting and Economics, 1994, volume 18, pp. 357-77. Bolton, Gary E., “A Comparative Model of Bargaining: Theory and Evidence,” American Economic Review, 1991, volume 81, pp. 1096-1136. Bosch, Jean-Claude and Insup Lee, “Wealth Effects of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Decisions,” Managerial and Decision Economics, 1994, volume 15, pp. 589-599. Camerer, Colin and Richard H. Thaler, “Anomalies: Ultimatums, Dictators and Manners,” 1995, Journal of Economic Perspectives, volume 9, pp. 209-219. Chalk, Andrew, “Market Forces and Aircraft Safety: The Case of the DC-10,” Economic Inquiry, 1986, volume 24, pp. 43-60. Chalk, Andrew J., “Market Forces and Commercial Aircraft Safety,” Journal of Industrial Economics, 1987, volume 36, pp. 61-81. Chauvin, Keith W. and James P. Guthrie, “Labor Market Reputation and the Value of the Firm,” Managerial and Decision Economics, 1994, volume 15, pp. 543-552. Cloninger, Dale O., Terrance R. Skantz, and Thomas H. Strickland, “Price Fixing and Legal Sanctions: The Stockholder-Enrichment Motive,” Antitrust Law and Economics Review, 1988, pp. 17-24. Davidson, Wallace N. III, Dan Worrell, and Louis T. W. Cheng, “The Effectiveness of OSHA Penalties: A Stock-Market-Based Test,” Industrial Relations, 1994, volume 33, pp. 283-296. Dowdell, Thomas D., Suresh Govindaraj, and Prem C. Jain, “The Tylenol Incident, Ensuing Regulation, and Stock Prices,” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 1992, volume 27, pp. 283-301. 26 Fry, Clifford L. and Insup Lee, “OSHA Sanctions and the Value of the Firm,” The Financial Review, 1989, volume 24, pp. 599-610. Hamilton, James T., “Pollution as News: Media and Stock Market Reactions to the Toxics Release Inventory Data,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 1995, volume 28, pp. 98-113. Hanka, Gordon, “Does Wall Street Want Firms to Harm Their Neighbors and Employees?” manuscript, November 25, 1992. Harper, Richard K. and Stephen C. Adams, “CERCLA and Deep Pockets: Market Response to the Superfund Program,” Contemporary Economic Policy, 1996, volume 14, pp. 107-115. Hayes, Arthur S. and Joseph Pereira, “Facing a Boycott, Many Companies Bend,” The Wall Street Journal, November 8, 1990, pp. B1 & B7. Helmuth, John A., Ashok J. Robin, and John S. Zdanowicz, “The Adjustment of Stock Prices to Wall Street Journal Corrections,” Review of Financial Economics, 1994, volume 4, pp. 6977. Hersch, Joni, “Equal Employment Opportunity Law and Firm Profitability,” The Journal of Human Resources, 1991, volume 26, pp. 139-53. Hoffer, George E., Stephen W. Pruitt, and Robert J. Reilly, “The Impact of Product Recalls on the Wealth of Sellers: A Reexamination,” Journal of Political Economy, 1988, volume 96, pp. 663-670. Ippolito, Richard A., “Consumer Reaction to Measures of Poor Quality: Evidence from the Mutual Fund Industry,” Journal of Law and Economics, 1992, volume 35, pp. 45-70. Jarrell, Gregg and Sam Peltzman, “The Impact of Product Recalls on the Wealth of Sellers,” Journal of Political Economy, 1985, volume 93, pp. 512-536. Kahneman, Daniel, Jack L. Knetsch, and Richard H. Thaler, “Fairness and the Assumptions of Economics,” Journal of Business, 1986, volume 59, pp. S285-S300. Karpoff, Jonathan and John R. Lott, Jr., “The Reputational Penalty Firms Bear from Committing Criminal Fraud,” Journal of Law and Economics, 1993, volume 36, pp. 757-802. Karpoff, Jonathan M., John R. Lott, Jr., and Graeme Rankine, “Environmental Violations, Legal Penalties, and Reputation Costs,” October 23, 1998, working paper, Social Science Research Network. Kihlstrom, Richard E. and Michael H. Riordan, “Advertising as a Signal,” Journal of Political Economy, 1984, volume 92, pp. 427-450. 27 Klein, Benjamin and Keith B. Leffler, “The Role of Market Forces in Assuring Contractual Performance,” Journal of Political Economy, 1981, volume 89, pp. 615-641. Klein, Benjamin, Robert G. Crawford, and Armen A. Alchian, “Vertical Integration, Appropriable Rents, and the Competitive Contracting Process,” Journal of Law and Economics, 1978, volume 21, pp. 297-326. Kreps, David M. and Robert Wilson, “Reputation and Imperfect Information,” Journal of Economic Theory, 1982, volume 27, pp. 253-279. Laplante, Benoit and Paul Lanoie, “The Market Response to Environmental Incidents in Canada: A Theoretical Analysis,” Southern Economic Journal, 1994, volume 60, pp. 657-672. Mathios, Alan and Mark Plummer, “The Regulation of Advertising by the Federal Trade Commission: Capital Market Effects,” from Research in Law and Economics, 1989, volume 12, edited by Richard O. Zerbe, Jr., JAI Press, Greenwich, Connecticut, pp. 77-93. Milgrom, Paul and John Roberts, “Price and Advertising Signals of Product Quality,” Journal of Political Economy, 1986, volume 94, pp. 796-821. Mitchell, Mark L. and Michael T. Maloney, “Crisis in the Cockpit? The Role of Market Forces in Promoting Air Travel Safety,” Journal of Law and Economics, 1989, volume 32, pp. 329356. Mitchell, Mark L., “The Impact of External Parties on Brand-Name Capital: The 1982 Tylenol Poisonings and Subsequent Cases,” Economic Inquiry, 1989, volume 27, pp. 601-618. Muoghalu, Michael I., H. David Robison, and John L. Glascock, “Hazardous Waste Lawsuits, Stockholder Returns, and Deterrence,” Southern Economic Journal, 1990, volume 57, pp. 357-370. Navarro, Peter, “Why Do Corporations Give to Charity?” Journal of Business, 1988, volume 61, pp. 65-93. Nelson, Phillip, “Advertising as Information,” Journal of Political Economy, 1974, volume 82, pp. 729-754. Nelson, Phillip, “Information and Consumer Behavior,” Journal of Political Economy, 1970, volume 78, pp. 311-329. Peltzman, Sam, “The Effects of FTC Advertising Regulation,” Journal of Law and Economics, 1981, volume 24, pp. 403-448. Peterson, Pamela P., “Event Studies: A Review of Issues and Methodology,” Quarterly Journal of Business and Economics, 1989 volume 28, pp. 36-66. 28 Rabin, Matthew, “Incorporating Fairness into Game Theory and Economics,” American Economic Review, 1993, volume 83, pp. 1281-1302. Reichert, Alan K., Michael Lockett, and Ramesh P. Rao, “The Impact of Illegal Business Practice on Shareholder Returns,” The Financial Review, 1996, volume 31, pp. 67-85. Rogers, T. J., “Profits vs. PC,” Reason, October 1996, pp. 36-43. Rothchild, John, “Why I Invest with Sinners,” Fortune, May 13, 1996, p. 197. Rubin, Paul H., R. Dennis Murphy, and Gregg Jarrell, “Risky Products, Risky Stocks,” Regulation, 1988, pp. 35-39. Schwartz, R. A., “Corporate Philanthropic Contributions,” The Journal of Finance, 1968, volume 23, pp. 479-497. Schwert, G. William, “Using Financial Data to Measure Effects of Regulation,” Journal of Law and Economics, 1981, volume 24, pp. 121-158. Shapiro, Carl, “Consumer Information, Product Quality, and Seller Reputation,” Bell Journal of Economics, 1982, volume 13, pp. 20-35. Shapiro, Carl, “Premiums for High Quality Products as Returns to Reputations,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1983, volume 98, pp. 659-679. Viscusi, W. Kip and Joni Hersch, “The Market Response to Product Safety Litigation,” Journal of Regulatory Economics, 1990, volume 2, pp. 215-230. 29 TABLE 1 Summary of Previous Event Studies Event Type Average Loss in $ Average Loss as Percentage of Value Cite(s) FTC cease-and-desist order for false advertising Automobile recalls as high as $250M for larger firms n.a. 3.2 – 6.4 FDA-mandated drug recalls FDA disciplinary actions Drug packaging regulations (subsequent to Tylenol poisonings) CPSC-mandated recalls EEO violations; EEO class-action suits OSHA sanctions $1.8M (residual) n.a. $310M 5.6 (residual) 2.22 – 3.42 11.83 $146M $18.5M $16M (residual) $3.9 – 22.1M 5.4 – 6.9 0.29 – 0.48; 15.6 0.53 - 2.1 Corporate indictments $9.15M (residual; not sig.) n.a. 1.38 – 3.1 Fry & Lee, 1989; Davidson, et al., 1994 Reichert, et al., 1996 17 Cloninger, et al., 1988 $33.3M 1.2 Muoghalu, et al., 1990 n.a. 0.85 net loss to full sample; no residual insignificant Karpoff, et al., 1998 Laplante and Lanoie, 1994 Charges and pleas in pricefixing cases Hazardous waste mismanagement suits Environmental violations insignificant Peltzman, 1981; Mathios and Plummer, 1989 Jarrell & Peltzman, 1985; Hoffer, et al. 1988 Jarrell & Peltzman, 1985 Bosch & Lee, 1994 Dowdell, et al., 1992 Rubin, et al., 1988 Hersch, 1991 Being named a potentially responsible party at a Superfund site Violation of Canadian environmental regulation n.a. Coca-Cola adopts New Coke Criminal fraud against stakeholders and government Tylenol poisonings (first wave) Bhopal, India chemical leak $500M $40 - 60.8M insig. for announcement; 2.0 for settlement 8.1 1.34 – 5.05 $1.24B (residual) 14.3 (residual) Mitchell, 1989 ~$1B (Union Carbide) n.a. (Union Carbide’s rivals) $4.1M $11 – 18.3M (residual) $21.32M 27.9 (Union Carbide) 1.28 (Union Carbide’s rivals) 0.28 1.34 – 1.55 (residual) 3.8 Blacconiere and Patten (1994) n.a. 0.28 – 2.2 Chauvin & Guthrie, 1994 Chemical releases reported Airline crashes before and after deregulation Aircraft-manufacturer-at-fault crashes Included in Working Mother’s “best” employers list n.a. Harper & Adams, 1996 Benjamin & Mitchell Karpoff & Lott, 1993 Hamilton, 1995 Mitchell & Maloney, 1989 Chalk, 1987 30 TABLE 2 Summary of Results for Various Windows All events: Significantly-positive-tosignificantly-negative ratio Total-positive-to-total-negativeratio (Probability of getting the actual split or even more skewed, assuming a .5 probability of a positive return) AAR or ACAR - % return (z-statistic) Average change in $ value ($K) t=-1 6:7 t=0 7:7 (-1,0) 8:10 (-5,0)a 7:6 (-1,9)b 4:7 45:53 (.48) 58:40 (.09) 52:46 (.61) 49:49 (1.00) 55:43 (.27) -0.2171 (-2.1041)‡ -4239 0.3907 (2.1815)‡ 8254 0.1736 (0.0538) 4018 0.2461 (0.0676) -19506 0.3353 (0.1531) 61656 Without events with (1) concurrent good news and significantly positive returns or (2) concurrent bad news and significantly negative returns: t=-1 t=0 (-1,0) (-5,0)a (-1,9)b 5:7 2:7 2:9 4:5 3:7 Significantly-positive-tosignificantly-negative ratio 38:51 50:39 44:45 42:47 48:41 Total-positive-to-total-negative(.20) (.29) (.99) (.67) (.53) ratio (Probability of getting the actual split or even more skewed, assuming a .5 probability of a positive return) -0.327 0.0768 -0.25 -0.14 -0.142 AAR or ACAR - % return (-2.6334)* (0.3366) (-1.6189) (-0.7754) (-0.6279) (z-statistic) -3532 2520 -1010 -12803 42582 Average change in $ value ($K) Without events with conflicting news and event 9: t=-1 5:6 Significantly-positive-tosignificantly-negative ratio 38:50 Total-positive-to-total-negative(.24) ratio (Probability of getting the actual split or even more skewed, assuming a .5 probability of a positive return) -0.177 AAR or ACAR - % return (-1.5991) (z-statistic) -3169 Average change in $ value ($K) t=0 1:7 (-1,0) 2:8 (-5,0)a 4:4 (-1,9)b 3:7 49:39 (.34) 44:44 (1.00) 42:46 (.75) 47:41 (.59) -0.023 (-0.3475) 2285 -0.200 (-1.3718) -882 -0.056 (-0.5445) -12724 -0.167 (-0.6806) 43005 * significant at 1% level ‡ significant at 5% level a These are estimates, because the estimation period and event window overlap for these calculations. b Because of data restrictions event 5 = (-1,5), event 7 = (-1,8), and event 9 = (-1,8). 31 TABLE 3 Explanatory Regression Results Intercept term or Coefficient on: Intercept term REPORTC REPORTR ACTIONF ACTIONP ACTIONM NEWSG NEWSB NEWSN Estimated Value (t-statistic - 86 d.f.) 0.01761 (0.5490) 0.00660 (0.7247) -0.00121 (-0.1065) 0.00710 (0.9664) 0.00212 (0.1813) -0.01320 (-1.124) 0.00437 (0.6848) -0.00439 (-0.3952) 0.00504 (0.4746) NEWSC TIME -0.00039 (-1.056) Estimated Value (t-statistic - 88 d.f.) 0.01964 (0.6344) 0.00752 (0.8479) -0.00006 (-0.0054) 0.00616 (0.8689) 0.00209 (0.1838) -0.01355 (-1.192) CARTER REAGAN BUSH SIZE 0.00755 (1.112) -2.2000E-11 (-0.1307) -0.00632 (-0.5164) 0.00543 (0.5746) -0.00138 (-0.1198) 0.00753 (0.9973) 0.00161 (0.1344) -0.01374 (-1.143) 0.00514 (0.7947) -0.00366 (-0.3249) 0.00671 (0.6216) 0.00303 (0.5642) -0.00042 (-1.160) FORD IND Estimated Value (t-statistic - 83 d.f.) 0.00744 (1.113) -3.2563E-11 (-0.1975) 0.00502 (0.4013) -0.01106 (-1.127) -0.01030 (-1.398) -0.00387 (-0.4721) 0.00484 (0.6598) -5.9286E-11 (-0.3450) 32 APPENDIX TABLE A-1 Summary of Events No. 1 2 Firm Event Description Event Date Shell Oil Standard Oil of California (Chevron) Detroit Edison Platform explosion Tanker collision 12/02/70 01/19/71 Soot release 08/28/73 Standard Oil of California (Chevron) Philadelphia Electric Co. Standard Oil of Indiana (Amoco) General Public Utilities Philadelphia Electric Co. (Peco) Rochester Gas & Electric Co. Long Island Lighting Co. (Lilco) Tank puncture 10/13/75 Radioactive release 10/10/77 Tanker spill 03/17/78 Radioactive release 03/29/79 Radioactive release 06/22/79 Radioactive release 01/26/82 Storage tank leak 02/12/85 11 12 13 Ashland Oil Exxon Exxon Storage tank collapse Tanker spill Pipeline spill 01/05/88 03/28/89 01/03/90 14 British Petroleum (BP) Olin Corp. Pipeline ruptured by tanker 02/08/90 Charged by Justice Dept. with water pollution 02/10/70 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 15 Other firm-specific news in event window On t-0, high temperatures led to record electrical demand; extra power bought from Canada On t=1, more developments in case of political football Shoreham plant On t=-1, seven plaintiffs’ lawyers appointed by state and federal court judges in AK to committee to coordinate litigation against company over Valdez spill On t=-1, Judge reduced three felony counts against Valdez captain to one 33 Table A-1 – continued 16 17 Public Service Electric and Gas Co. Texaco Charged by Justice Dept. with water pollution Charged with by Justice Dept. water pollution Charged by Justice Dept. with water pollution 02/10/70 18 Mobil Oil 19 Atlantic Richfield Co. (ARCO) Charged by Justice Dept. with water pollution 02/19/70 20 Phillips Petroleum 02/19/70 21 Standard Oil of Indiana (Amoco) & its sub. American Oil Co. Charged by Justice Dept. with water pollution Charged by Justice Dept. with water pollution 22 Florida Power & Light 02/25/70 23 Standard Oil of California (Chevron) 24 Consolidated Edison of NY (Con Ed) 25 Standard Oil of California (Chevron) Nixon administration threatened to file suit (and later did) to stop construction of a hot water canal (potential thermal pollution) FTC & California Air Resources Board dispute company’s claims concerning the environmental friendliness of gasoline additive Alleged thermal and chemical pollution, first news mentions dead fish Oil platform explosion leading to subsequent oil slick 26 Standard Oil of New Jersey’s sub. Humble Oil & Refining Co. Oil spill; tanker chartered, but not owned or operated, by company; subsequent State suit 02/16/70 27 Shell Oil Co. 03/30/70 28 Standard Oil of New Jersey’s sub. Humble Oil & Refining Co. Interior Secretary ordered three drilling platforms closed down for alleged violations of safety regulations Private suit alleging pollution caused physical and mental harm to humans and livestock 02/10/70 02/19/70 02/19/70 03/02/70 On t=-1, one of five firms to relinquish rights to dawsonite oil-shale tracts On t=-1, one of five firms to relinquish rights to dawsonite oil-shale tracts On t=0, elected a director and a president of a sub. On t=0, received a $3.2M DSA contract for fuel oil and gas 03/11/70 02/11/70 08/26/70 On t=0, one of three refiners saying that they will market unleaded fuel when car makers produce compatible engines On t=-1, named a president of a subsidiary On t=+1, rights offering for common shares valued at $387M became effective On t=+1, Humble plans to raise $50M by offering abroad $30M of 5-year notes and $20M of 15year debenture 34 Table A-1 – continued 29 Mobil Oil Corp. Fined by NY state judge for failing to halt discharge of industrial waste 10/06/70 30 Mobil Oil Corp. 10/14/70 31 Standard Oil of New Jersey’s sub. Humble Oil & Refining Co. 32 Continental Oil 33 Union Oil of California 34 Tenneco Oil Co. 35 Gulf Oil Corp. 36 Kerr-McGee Corp. 37 Mobil 38 Cleveland Electric Illuminating Co. Olin Corp. U.S. attorney filed criminal informations for water pollution Justice Dept. charged company with knowingly failing to provide subsurface safety devices on offshore wells Charged by Justice Dept. with failing to install and maintain subsurface safety devices on offshore wells Charged by Justice Dept. with failing to install and maintain subsurface safety devices on offshore wells Charged by Justice Dept. with failing to install and maintain subsurface safety devices on offshore wells Charged by Justice Dept. with failing to install and maintain subsurface safety devices on offshore wells Charged by Justice Dept. with failing to install and maintain subsurface safety devices on offshore wells Charged by Justice Dept. with failing to install and maintain subsurface safety devices on offshore wells Charged by federal grand jury with water pollution Charged by federal grand jury with water pollution 39 11/16/70 On t=+1, announced plans to increase output of some fuels to ease anticipated winter shortage On t=-1, Libyan affiliate agreed to raise posted price of Libyan crude On t=0, lifted wholesale prices of some oils and kerosene in East 11/23/70 11/23/70 12/23/70 12/23/70 On t=0, offered 8% increase in 1971 wages, 6% in 1972, topping other refineries 12/23/70 12/23/70 04/30/71 04/30/71 On t=0, second quarter earnings to be substantially ahead of first quarter On t=0, reported a quarterly dividend was to be paid on 06/09 On t=+1, received $4.3M contract to operate Army ammunition plant 35 Table A-1 – continued 40 Shell Oil Charged by federal grand jury with water pollution 04/30/71 41 Crown Central Petroleum Corp. 05/04/71 42 44 Atlantic Richfield Co. (ARCO) Union Oil Co. of California Signal Oil Co. 45 Getty Oil Co. 46 Atlantic Richfield Co. (ARCO) Amerada Hess Corp. Charged by FTC with making false antipollution claims about a gasoline additive Charged by Justice Dept. with water pollution Charged by Justice Dept. with water pollution Charged by Justice Dept. with water pollution Charged by Justice Dept. with water pollution Charged by Justice Dept. with water pollution Charged by Justice Dept. with water pollution Charged by Justice Dept. with water pollution Sued by Justice Dept. to clean up an earlier oil spill Sued by car dealer for damage to his cars from air pollution Charged by Justice Dept. with water pollution Sued by environmentalists for violating election laws by setting up a “front group” to oppose a proposed clean environment statute to avoid publicity Oil spill Pennsylvania Insurance Commissioner issued “Investor’s Guide to Polluters” listing firms and government units the state is taking action against for pollution so that insurance companies could “use their investment program to end activities of polluters” 43 47 48 49 Coastal States Gas Producing Co. Texaco 50 Consolidated Edison Co. (Con Ed) 51 Olin Corp. 52 Standard Oil of California (Chevron) 53 54 Texaco Sun Oil Co. On t=-1, announced $25M expansion of oil refinery to produce components for lead-free gas 05/19/71 05/19/71 06/01/71 06/01/71 06/01/71 On t=0, ordered $13.2M storage vessel 06/22/71 06/22/71 06/28/71 06/29/71 09/21/71 03/08/72 07/25/72 09/29/72 On t=+1, exec. VP retires in ill health 36 Table A-1 – continued 55 Gulf Oil Corp. 56 Standard Oil of California (Chevron) 57 Potomac Electric Power Co. 58 Central Illinois Lighting Co. 59 Union Electric Co. 60 Exxon Corp. 61 Texaco Inc. 62 63 Consolidated Edison Co. (Con Ed) Exxon Corp. 64 Tampa Electric Co. 65 Chevron USA 66 Gulf Oil Corp. Pennsylvania Insurance Commissioner issued “Investor’s Guide to Polluters” listing firms and government units the state is taking action against for pollution so that insurance companies could “use their investment program to end activities of polluters” Issued notice of violation of Clean Air Act by EPA for constructing new storage tanks without EPA approval Notified by EPA that plants were in violation of state emissions regulations Notified by EPA that plants were in violation of state emissions regulations Notified by EPA that plants were in violation of state emissions regulations Charged by Justice with water pollution 09/29/72 Charged by Justice Dept. with water pollution Received notice of emissions violation from EPA Agreed to consent order with EPA for dumping drilling waste into sea Florida Department of Environmental Regulation filed suit alleging company is constructing a generator without a permit Ordered by Bay Area Pollution Control District to close a refinery because of an earlier agreement to limit pollution (later ruled by a judge to be misinterpretation of the agreement) Agreed to proposed consent judgement with a Justice Dept./EPA regarding water pollution at a refinery 12/02/74 02/06/74 06/10/74 06/10/74 06/10/74 On t=0, received rate boost of $39.9M 12/02/74 On t=-1, one of 3 companies to tell AEC they plan pilot plants to make nuclear fuels On t=-1, plans to deter project to convert coal to natural gas 04/02/75 On t=+1, asked for record increase in electric rates 09/03/76 03/18/77 11/25/77 On t=-1, consortium headed by co. placed contract for outside firm to operate CO2 pipeline in SW Texas 01/23/78 On t=-1, a joint venture involving Gulf hired a contractor in development of oil shale tract 37 Table A-1 – continued 67 Ohio Edison Co. 68 Philadelphia Electric Company (PECO) 69 Carolina Power and Light Co. (Carolina P&L) Ethyl Corp. 70 71 72 Cleveland Electric Illuminating Co. Atlantic Richfield Co. (ARCO) 73 Southern California Edison 74 Mobil Oil Corp. 75 Exxon Corp. 76 Commonwealth Edison Co. (Com Ed) 77 Texaco Sued by EPA for violation of state’s air pollution regulations Plants found in violation of air pollution control standards by EPA Fined by NRC for improperly disposing of radioactive materials Charged in administrative complaint by EPA with using leaded gasoline in company-owned vehicles designed for unleaded fuel Sued by EPA for violating emissions standards at plants EPA plans fine for using leaded gasoline in company cars designed for unleaded fuel 08/03/78 Reached an out-of-court settlement with the state air resources board and local air quality officials on a dispute over emissions Suit filed and settled with Alabama over water pollution charges NY state environmental officials asked NY state attorney general to take action for alleged water pollution violations Sued by Justice Dept. on behalf of EPA to force an expanded cleanup of toxic spillage from electrical equipment Fined by EPA for water pollution; no finding of liability 03/11/82 11/24/78 08/08/80 On t=+1, placed contract for power plant simulator/training center 03/19/81 03/19/81 04/30/81 On t=-1, net income figures out On t=0, separately, but in the same article ARCO completed a 3-year shipping agreement to build an 80-mile pipeline across Panama leading to about $100M in shipping tariffs over 3 years 09/28/82 10/17/83 On t=+1, company mentioned in “Heard on the Street” column; news unclear 02/22/84 On t=+1, placed large order with Swiss firm 08/22/85 On t=-1, another company to buy Texaco’s 50% stake in $1.4B copper-mining project in Chile 38 Table A-1 – continued 78 Atlantic Richfield Co. (ARCO) Fined by EPA for water pollution; consent decree 08/22/85 79 Chevron USA Penalty judgement won by EPA in civil suit for air pollution 10/07/85 80 Ashland Oil Inc. 07/08/86 81 Texaco Inc. 82 Chevron USA Civil complaint and consent decree with Justice Dept. over charges of persistent water pollution at a refinery Sued by EPA for air pollution Sued by US Attorney’s office for water pollution 83 Atlantic Richfield Co. (ARCO) 01/05/87 84 Atlantic Richfield Co. (ARCO) 85 Chevron Corp. 86 Amerada Hess Corp. 87 Atlantic Richfield Co. (ARCO) Signed consent order with NY State Department of Environmental Conservation to clean up pollution from a defunct refinery (site is on Superfund list) Agreed to settle charges of illegally releasing waste water and sludge into LA County water treatment facility Sued by US attorney on behalf of EPA for violating benzene rules Sued by state of Alaska for not preventing contamination of shoreline from Valdez spill Sued by state of Alaska for not preventing contamination of shoreline from Valdez spill On t=-1, to sell one-third interest in Stillwater Mining Co. for $15M On t=0, plans to offer up to $200M of adjustablerate notes that mature in 9-48 months to raise $1.2B On t=-1, year-old acquisition of company used as a comparison to current action of another firm in “Heard on the Street” column On t=+1, SEC charged the company and one of its chairmen with foreign bribery 07/16/86 08/27/86 On t=-1, mentioned in “Heard on the Street” that company’s stock would be a good value if energy prices turnaround 05/29/87 08/31/88 08/16/89 08/16/89 On t=0, company to introduce low-emission regular gas to So. Calif. market on 09/01 that will “significantly reduce air pollution” from older cars that don’t have catalytic converters 39 Table A-1 – continued 88 British Petroleum Co. 89 Mobil Corp. 90 Phillips Petroleum Co. 91 Unocal Corp. 92 BP America 93 Unocal Corp. 94 BP Oil 95 Exxon Corp. 96 BP Oil 97 Mobil 98 Exxon Co. Sued by state of Alaska for not preventing contamination of shoreline from Valdez spill Sued by state of Alaska for not preventing contamination of shoreline from Valdez spill Sued by state of Alaska for not preventing contamination of shoreline from Valdez spill Sued by state of Alaska for not preventing contamination of shoreline from Valdez spill Sued by fishermen for spill by another company’s tanker because at-fault party contesting liability Settled suit brought by Sierra Club over water pollution Consent decree with US Attorneys office and EPA for water pollution from refinery Cited by EPA for violations of Clean Water Act for unauthorized tank washing transfers to the water treatment facility (no actual pollution; dispute over meaning of permit) Cited by EPA for violations of Clean Water Act for unauthorized tank washing transfers to the water treatment facility (no actual pollution; dispute over meaning of permit) L.A. County officials filed suit for an earlier oil spill when a pipeline failed Fined by EPA for violating air and chemical reporting regulations 08/16/89 On t=-1, BP Chemicals’ silicone surfactant business bought by a Union Carbide division 08/16/89 08/16/89 08/16/89 10/23/89 02/23/90 10/24/90 08/23/91 08/23/91 01/10/92 12/04/92 Dividend will be paid at later date to shareholder of record on t=0 40 TABLE A-2 Abnormal Returns, Gross Losses, & Costs Event-by-event results using (1,0) window: Event # 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 Information on Direct Costs Reported in WSJ $47M, $3.3M of which was insured, + $210K/day for ~1 month and $53K/day in lost production, + liability for people killed Lawsuits filed for $3.5B; $6M in cleanup and private damages; $2500 fine n.a. n.a. ? fines on similar incidents $40K - $200K $75M cleanup costs; $204M (14 years later), had $50M in insurance >$60M in damages; >$1B in lawsuits n.a. Replacement power $280K/day for 4 months + repairs est. to be > $1M deductible Cleanup costs; ≤$5000 fine ~$18M cleanup, fines, claims (settled within 18 months) $B’s $18M in 2 suits (settled within 18 months) + cleanup costs? $3.9M (5 years later) + cleanup costs? ≤$2500 fine, compliance? ≤$135,000 fine, compliance? ≤$135,000 fine, compliance? ≤$2500 fine ≤$2500 fine ≤$2500 fine ≤$2500 fine $2500 fine + $35M over next 4 years on pollution control Compliance? State sued for $5M; compliance? Fined $1M; $31.5M private suit filed $250M suit filed $340,000 fine $1.2M suit filed $10,000 fine + compliance? $2500 fine $300,000 fine $242,000 fine $24,000 fine $32,000 fine $250,000 fine ≤$20,000 fine ≤$150,000 fine Change in Change in value value ($K) (%÷ 100) 0.03394 102046 0.01804 78066 -0.00847 0.01784 -0.00184 -0.00285 -0.06263* -0.01938 -0.04679‡ -6270 93534 -2597 -19967 -68258 -23371 -12284 0.00082 -0.0427§ -0.0181§ -0.0264§ -0.01887 -0.02351 0.00241 0.00407 0.0979* 0.0529§ 0.0472§ 0.02029 0.01225 ‡ -0.0361 -0.00397 -0.02713 -0.0320* -0.00745 -0.01976 0.02762 0.00267 -0.02308 0.02586 -0.02233 0.01766 0.02735 -0.00601 -0.01528 731 -76564 -1654658 -861123 -68324 -10620 1952 27842 368706 138621 70759 54852 12341 -147046 -4353 -105012 -359357 -20896 -296112 148563 14539 -354897 37325 -20850 22501 171042 -4648 -83942 41 TABLE A-2 – continued 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 Suspended fine of $10K, but must agree to spend $31.5M on pollution control ≤$375,000 fine ≤$2500 fine n.a. ≤$2500 fine ≤$7500 fine ≤$5000 fine ≤$2500 fine ≤$5000 fine ? ≤$2500 fine ? ≤$2500 fine $65,000 suit filed $2.3M suit filed ≤$7500 fine n.a. $15M in suits filed; cleanup costs? n.a. n.a. Compliance costs = n.a.; possible fines if no compliance 2 years after incident fined $37,500 and ~$37M/each spent on 3 plants’pollution control equipment Compliance costs = n.a. Compliance costs = n.a. ≤$2000 fine ≤$30,000 fine Compliance costs = n.a. $100,000 fine; some compliance costs? $6.8M suit filed; plus loss of use of facility? Won in court, legal costs = n.a. $15,000 penalty + compliance costs Compliance costs ~$400M (uncertain timetable; order for equipment 2.5 years later); $1.55M penalties, $100M spent already ~$100M more in compliance costs n.a. ≤$422,000 fine; compliance? Potentially $M’s in fines; compliance? 2 years later sued for ≥$330,000; compliance? Compliance? $2M in penalties; $500,000 cleanup $500,000 private settlement and $1.5M government settlement (within 1 year) Compliance? $600,000 fine $340,000 fine $6M penalty $765,500 penalty plus compliance?; private suit settlement? Suit seeks $M’s in fines and compliance -0.02305 -12021 0.03861 -0.01139 0.00565 -0.00267 0.00637 0.04147 0.02695 0.01254 -0.0544‡ 0.02028 -0.01840 0.01030 0.01032 -0.00003 0.00530 0.01218 0.02289 0.00616 -0.01805 22625 -37992 217 -8682 6943 15383 45335 38880 -43277 18409 -177979 12009 5017 -1246 45047 16502 111692 30185 -6049 0.00638 0.0640* 0.02471 0.02809 -0.00778 0.00087 0.00004 -0.01318 -0.01198 0.0358* 632 25513 340244 159552 -5387 20547 12 -89565 -58977 33547 -0.00927 -0.00076 -0.0579‡ 0.01769 ‡ 0.0519 -0.0260§ -0.00991 0.00951 -11506 -689 -37156 12689 587068 -72746 -102963 317178 0.00597 0.01208 0.00324 -0.01481 -0.00752 -0.00726 22836 102401 41870 -195699 -13571 -51315 42 TABLE A-2 – continued 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 Suit seeks $8.8M in fines and compliance - $36M over past 3 years + $50M over next 20 Agreed to $6M in cleanup costs over 2 years then possibly more $581,000 settlement $M’s in penalties sought + compliance (questionable if already in compliance) n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. $104.8M suit filed (liability not clear) $5.5M settlement; already in compliance $2.3M fine n.a. n.a. n.a. $178,000 fine n.a. = not available in WSJ § = return is significantly different from zero at 0.1 level of significance ‡ = return is significantly different from zero at 0.05 level of significance * = return is significantly different from zero at 0.01 level of significance 0.0425§ 615436 -0.00816 -0.01891 -0.00223 -86401 -297069 -34045 -0.02291 0.00492 -0.00088 § 0.0246 -0.01139 0.00032 0.00020 -0.02807 0.01452 0.00570 0.02324 -0.01818 0.02065 -73927 86052 -2097 524338 -66149 1806 513 -202769 50443 412924 50091 -476997 1499452