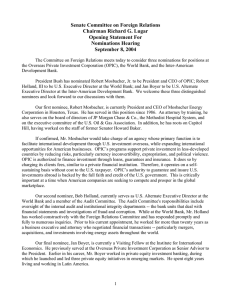

Inside the Portfolio of the Overseas Private Investment Corporation

advertisement