CULTURAL LANDSCAPE REPORT OF IRVINGTON, A CREATIVE PROJECT

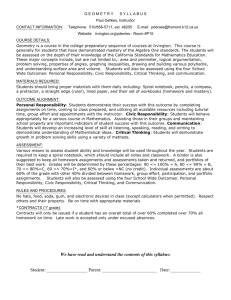

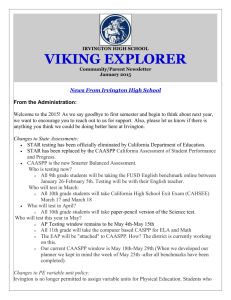

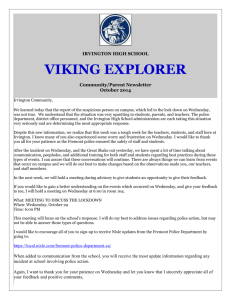

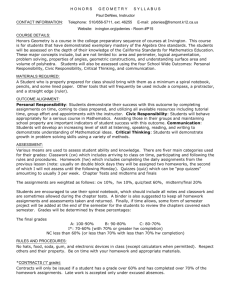

advertisement