HOUSING OPTIONS IN TASHKENT: JOURNEYS OF YOUNG PEOPLE IN ESTABLISHING THEIR HOUSEHOLDS

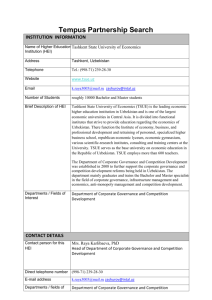

advertisement