Responsibility for war crimes before national courts in Croatia Abstract

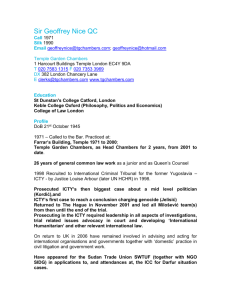

advertisement