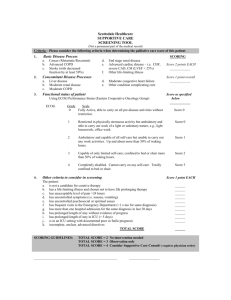

DETERMINANTS OF HEART FAILURE SELF-CARE BEHAVIORS A RESEARCH PAPER

advertisement