CERTIFIED DIABETES EDUCATORS’ PERSPECTIVES ON THE EFFECTIVENESS

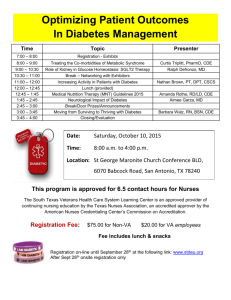

advertisement