CHARACTERIZING WRITING TUTORIALS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL

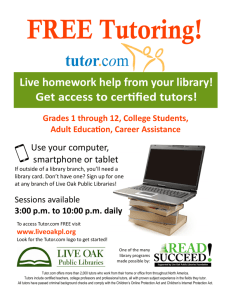

advertisement