“GOOD FENCES MAKE GOOD NEIGHBORS”: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF... COMPOSITION AND INTRODUCTORY CREATIVE WRITING CLASSROOMS

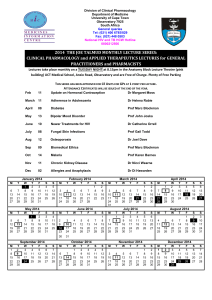

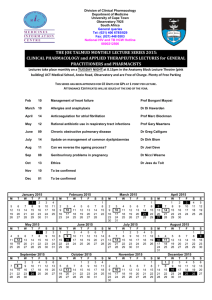

advertisement